Richard Foster unfurls a life in maps and survey books.

“Oh God, there are more of them,” I tell my brother. A wardrobe’s false top in our late parents’ old bedroom reveals yet another bulky roll of metre-long 1/2500 ordnance survey maps. Clearing out the family home of fifty years is an intense, often traumatic experience. There are times where you can laugh, though. Our dad’s habit of marking out his daily life and ambitions over the years, on any kind of paper that came to hand, often had us smiling. What the hell had he saved all these huge maps for?

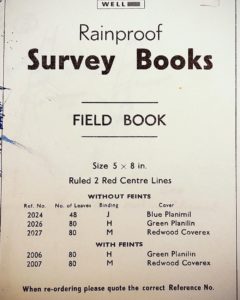

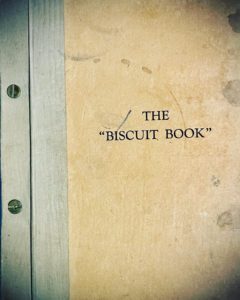

Investigations in the loft uncover an old plastic bag, encased in dust and obviously full of books or diaries of some sort. The bag reveals a pile of trim, hand-sized surveying notebooks, proudly touted as “rainproof”, with two red lines running down the middle of each page. At the bottom of the pile, its rough, thick cover jutting out at an awkward angle, is a strange looking tome called The “Biscuit Book”. Stained and cuffed, it bears the unmistakable mark of outdoor life and of being regularly used. Full of pages that are pre-folded and of various thickness, it is bound by two metal flathead screws. The “Biscuit Book” seems too incongruous to sit neatly in any bookshelf. It’s certainly not made for that, either. If this book took human form it would surely be the country cousin of yore, clad in battered tweed and reinforced brown brogues, shuffling around awkwardly, next to its sleek city relatives.

Something tells me that, however cumbersome or odd, I have to take all these things home. Back in the Netherlands, I immerse myself in the notebooks and try to make headway with The “Biscuit Book”. This copy, the 1956 edition, is a working book and as such doesn’t beat about the bush with fancy stuff like the history of surveying. Nonetheless in its opening pages it gives the lay reader tantalising hints and, in this age of satellite, increasingly forgotten facts about how Britain was mapped. The opening sentence is a thing of beauty: ‘The triangle is the basis of all ground survey for the making of maps and plans.’ There is also brief mention of the Primary Triangulation Points, ‘placed at an average of 40 miles distance, such as York Minster, Danbury Church Spire and the Cross of St. Paul’s Cathedral.’ A notice that brings Hawksmoor, or Watkins heretically to mind. Following this introduction is the forbidding user manual; complete with a detailed, illustrated appendix; giving full photographic instructions on how to identify and look after your Kern Extended Rod on the Model 175 Tripod. Elsewhere an illustration (Fig. G 10 to be precise) shows how one should signal to a colleague in the field using hand gestures. The final picture, where the figure seems to mimic a bird in flight with full, flapping arm gestures, denotes that the person with the marking equipment should ‘immediately plant their pole.’ The figure illustrating these hand gestures is drawn wearing plus fours and a country jacket and tie.

This is serious stuff. In essence, it teaches the language of how we describe the land. I think of my dad and his contemporaries cramming this information into their minds and formulating it into their worldviews. A teenaged Dad, toying with Teddy Boy fashions on Tyneside and about to do his National Service in the second battalion of the Coldstream Guards, learning about the mysteries of “red detail” and how to map a small area using a chain survey (in lay terms, mapping out ground using horizontal measurements and describing the boundaries of a plot or area of land, as well as other distances and angles on the ground surveyed). Out of the army and his map reading skills honed further by virtue of his experiences in an F.O.O. team, he applied for a job in the Archaeology Division of the OS. Interviewed by the legendary Charles Phillips of the 1939 Sutton Hoo dig, he got the job after talking to Phillips about Schubert and string quartets.

From the stories he shared, it seemed Dad loved working on the land for the Archaeology Division. Anecdotes of engines falling out of the bottom of cars, car windows held in by masking tape, terrible digs run by Victorian ladies looking to make ends meet, Lancastrians still wearing clogs on cobbled streets and farmers brandishing guns all now seem the stuff of Arthurian legend, even if this was my dad’s life, and in my reckoning, not all that long ago. Some vignettes stick in my mind for no reason. One acquaintance from his time tramping the moorlands around Rochdale and Rossendale was a small, permanently jolly character — let’s call him Sweeney — who called everybody “Little Master” and lived solely off meat and potato pies and beer. That is, until he collapsed and was taken to hospital, to begin a new life on a different diet. He talked of the strange attitudes he first encountered when first surveying in East Lancashire; his light Geordie lilt embroidering the tale. “I was in a field, taking measurements and practising a light aria, when I noticed I was being laughed at and pointed at by two farm girls. They’d never heard opera! I thought, ‘don’t they have culture in these Lancashire hills?’” I wouldn’t claim Windy Nook in Felling, where the Foster family seat was situated, is a place where one regularly encounters a gaggle of tenors out for a stroll, but maybe he still felt a debt of gratitude to Charles Phillips that needed periodic airing.

Over the years he mapped a huge amount of country, mainly Lancashire and Pembrokeshire. Sometimes to our detriment: as a family we never holidayed in Wales, because he knew the land so well, and never felt the need to go again. The notebooks bear these micro-experiences out, with meticulous registrations of obscure corners of the North, such as Whitehill Road, Peel, where Dad states ‘Extra Gullies found.’ This discovery was in early April 1974, precisely a month after my brother was born.

The notebooks also bear witness to the other side of Dad. They are a curious amalgam of work and his autodidactic, creative personality given vent and order. These diversions have a long history, starting in the late 1940s with his and his brothers’ Subbuteo league tables, obsessively noted and illustrated in the yearbooks of Windy Nook and District Housing Association, which my granda chaired as a Labour councillor. Thirty years later, computations for Tardy Gate (Ground floor – 10’ht., Dividing wall – Angled) suddenly morphs into a Latin primer, with first declensions and singular and plural forms set out neatly in pencil.

Dad later worked in Preston and ended up working in an office for the Greater Manchester Council, mapping police property until early retirement in the 1990s. He never really said much about his work at this point. The idyll of going out into the open after a hearty breakfast and mapping Bronze Age settlements (and spending afternoons asleep with his surveyor pals in digs, according to my mother, who once unwisely spent a field trip with her new husband) must have seemed far away. Apparently James Anderton was a “rum fellow.”

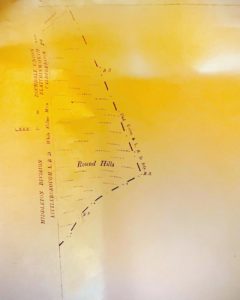

Amongst the roll of maps I salvaged, there is one that I keep going back to. It is 75 x 106 cm in size, and has one slightly rough edge, the left, which seems to have been carefully prised away from the copying machine’s cutter. The top edge has a plastic coated perforated strip neatly attached to it with sellotape. Probably added so it could be attached to a board, the strip gives the map the impression of another life as a giant exposed negative, a feeling enhanced by the fact that someone, probably Dad, has written LXXX I 4 in the top right hand corner. The map is discoloured, the rich yellow stains showing how some element used in the antiquated copying process has migrated through the grain over time. Other, more bleached parts may betray years of lying rolled up in a sunny spot. The back reveals its age. Under the stamped heading LANCASHIRE RECORD OFFICE, we get the subheading REFERENCE: with (marked out by hand in neat blue biro, though I am sure this is not Dad’s hand) a reference: 0. 5 . 25” Sheet 81/4 , c. 1893 ED. This map is dated (in the same orderly hand) 13:7:83. A final stamp tells us the map is COPYRIGHT RESERVED.

The margins on the front of the map tell us — as maps are wont to do — what we are looking at. Under the perforated strip are italicised capitals, denoting in this order:

YORKSHIRE WEST RIDING SOWERBY DIVISION TODMORDEN UNION TODMORDEN L.B.D.

At the bottom in much smaller italicised capitals we see:

HALIFAX UNION SOYLAND L.B.D. SOYLAND PH.

I presume that these places mark the authorities that border the land surveyed. Elsewhere, we are given the map’s legend and provenance. First surveyed in 1891, and ‘photozincographed and published at the Ordnance Survey Office, Southampton’ in 1893, this is a map of Blackstone Edge Moor. Underneath this title, though in much smaller capitals and with no explanation as to why, we see the name, Chelburn Moor. The scale is 1/2500, ‘being 25.344 Inches to a Statute Mile or 208.33 Feet to One Inch.’

What is there to see? In the top left corner we get a vaguely triangular shape denoting elevated ground with the words, Round Hills. Along their border, the words Union & LBD Bdy are marked. Now and then we see the letters B.S.. In the margin directly adjacent, are the following place titles:

MIDDLETON DIVISION

LITTLEBOROUGH L.D.B.

Reading upwards along the margin, we see these names, formatted in this manner:

ROCHDALE UNION

BLATCHINWORTH AND

CALDERBROOK PB.

Intersecting these two the words White Holme Moss and LXXXI. 3 3 3.

At the bottom left we see the top right of the circumference of a circle that simply says, Mound Mound Mound Mound Mound.

To the left in the margin we see these same words, in slightly different order

MIDDLETON DIVISION

ROCHDALE UNION

LITTLEBOROUGH L.D.B.

BLATCHINWORTH AND

CALDERBROOK P

Other markings arrayed around the corner of the map are LXXXI. 3 and reference numbers 305 and 1659310.

The index at the bottom, with the ‘characteristics and symbols of the boundaries’ of the map, lists the demarcations we have to look out for. The line delineating the two features I have mentioned — a long thick broken line — reveals itself to be the county border between the West Riding of Yorkshire and Lancashire.

And, apart from these two instances of elevated ground, jutting like prominentaries into the ocean, the rest of the map shows us absolutely nothing.

So why had Dad saved it?

I don’t know. But I increasingly see this map as a metaphor for the lives of those others we share our lives with. We can add details of time and place while we can, filling in corners in great and obscure detail, but the map itself remains essentially bare, and prey to our fading imaginings.