Luke Turner considers the fetishised landscape of Dungeness.

Photo: James Ginzburg

The Dungeness landscape lends itself to myth-making. It seems otherworldly against the bucolic rolling hills and patchworked fields of the rest of Kent, or the discrete woodland suburbia of the southern home counties, the Ravilious calm of the Downs, and the agribusiness farmland north of London. We try to categorise to make sense of such mystery in the claim that the banks of shingle and their arid appearance make the headland ‘Britain’s only desert’ – according to meteorologists, it isn’t. Dungeness’s oddness has increasingly made it a tourist destination. The former fisherman’s huts have been tarted up, painted, glazing expanded, a shiny stove pipe poking out of the roof.

In the nearly thirty years since Derek Jarman’s death, I wonder if something similar has happened with his work. For all the recent public awareness of his former home at Prospect Cottage, most of Jarman’s films are hidden away on subscription streaming services and seem unlikely to get the kind of mainstream broadcast that enabled many of us to find them back in the 1980s and ’90s. There’s a risk that cult status, or occult status, obscures the work itself, much as fetishising landscapes as uncanny obscures their human histories. A place, like a body of work, cannot exist in pleasure and leisure or quasi-magical dimensions alone.

On an early trip to Dungeness, many years ago, I felt that a man fully dressed as Father Christmas riding up and down the coast road on a gaudily festooned scooter could have materialised right off Jarman’s cutting-room floor. These days I am more wary of such flights of fancy. Although his films are often impressionistic engagements with the landscape, we might better see them as sparks that illuminate Dungeness in lurid relief, like a hissing flare over a wartime battlefield. Using this topography, Jarman made hard political points, about power, prejudice, the AIDS crisis, and England itself. These are stories with real lives at their heart.

Photo: Alexander Tucker

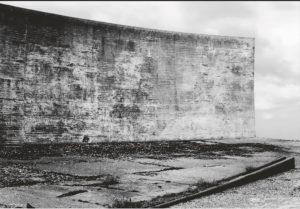

I hope that we do not risk losing sight of Dungeness for what it was and is: an industrial and often martial landscape of hard work with metal and concrete against wind and saltwater waves. Prospect Cottage was, after all, Jarman’s workshop. I think of those who built and stationed the Royal Military Canal, the Napoleonic-era Redoubt and Martello Towers, and the sound mirrors. I think of the crews of the armoured trains that rattled along the Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway, and of the soldiers and engineers who laid PLUTO (Pipe Lines Under The Ocean) across the English Channel to send fuel to the Allied forces in Europe in 1944. They did so from pumping stations disguised as seaside homes. I think too of the staff of the nuclear power station, a beautiful hulking beast on the very end of the land.

This has long been a tough, elemental place to work. Nobody knows that more than the fishermen of Dungeness, who found space for Keith Collins among their crews, and who continue to risk their lives for our tables. Prospect Cottage and its garden, then, shouldn’t be seen as the focal point of Dungeness: a place of pilgrimage and chapel to Jarman and his work, or as a horticultural and aspirational bohemian attraction like Sissinghurst or Charleston. A better view might be to rise above the churning coastline so to achieve the distance where the black and yellow timber house escapes the fetters of being branded ‘iconic’ – that most abused of words. It is then just another building, a place of work and love and shared labour, equal to the twisted rails, seized winches, shattered boats, crumbling concrete defences, and crab boilers, wonky on the shoreline. They are all simple, brusque memorials to tough lives, just as Jarman’s films, books, and art are often a celebration of masculinity and queer defiance. I see that strength embodied in the Dungeness landscape too, where the wind over shingle might be heard to hum with ghosts and the memory of their toil.

*

This piece is an excerpt from ‘Fifth Quarter’, an anthology about Derek Jarman, Keith Collins and Dungeness which accompanies the release of Alexander Tucker’s upcoming album ‘Fifth Continent’, a posthumous collaboration with Collins. Both book and album are released on 24th February via Subtext Recordings. More info here.

A launch event takes place at London’s Cafe OTO on 7th February, with performances from Alexander Tucker, Kenichi Iwasa, Maxwell Sterling, Simon Fisher Turner, Penelope Trappes & Paul Purgas (DJ). More info here.

Luke Turner is the author of ‘Out of the Woods’ — a memoir about sexuality, shame and the lure of the trees — as well as the upcoming ‘Men at War: Loving, Lusting, Fighting, Remembering 1939-1945’, published by Orion in April.