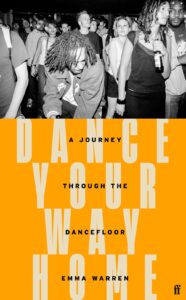

Emma Warren’s ‘Dance your Way Home: A Journey Through the Dancefloor’ — our Book of the Month for March — is an ode to the power and necessity of movement, writes Tara Joshi.

I am often an enthusiastic presence on a dance floor. There are photographs and videos of me as a chubby toddler wriggling to my parents’ Bollywood tapes, I did standard sparkly childhood ballet, I was a huge fan of making up dubious choreographed routines at school discos; and, even now, I love being in the club with the bass reverberating in my chest, laughing with friends as they catch wines in a humid crowd at carnival, or else dancing alone, swaying my hips in the company of my reflection in my bedroom mirror.

Still, I would never have described myself as “a dancer” (and certainly not a good one). That is, until reading Emma Warren’s beautiful new book, Dance Your Way Home: A Journey through the Dancefloor, which counters that mentality. From the opening, Warren (who contributes to Caught by the River herself) posits that, actually, we are all dancers – and as the book fluidly unravels, it becomes more and more clear just how important that sentiment is. As she puts it at one point, ‘The more we improvise movement, together, the better chance we have of thickening our relationships, building the necessary connections we need for a future that looks increasingly low resource and local.’ As this might suggest, Dance Your Way Home is, in some ways, a manifesto – an ode to the power and necessity of movement, especially when it is so often done in increasingly dwindling shared spaces.

This book is an intertwining of cultural and personal history. Brimming with memory alongside thorough research and thoughtful interviews, and examinations of how music informs dance and vice versa, the importance of dance as a political act – as a place for resistance and, simultaneously, something often clamped down upon by authority (be that over-policing by church or state) – is a throughline in the book. On some level, it is a consideration of who is valued by those who are in power. For example, questions about trying to understand where you fit into dance as you get older (‘There aren’t many places for middle-aged women to take up space […] and it’s good for middle-aged women to take up space,’ her friend Kate Ling tells her late into the book) sit alongside the closure of youth clubs and spaces for young people to congregate. Tacitly, Warren asks us: which bodies get access to the dance? She weaves together the possibilities of intergenerational dance, of cross-cultural dance (at one point, she shows a couple at the English folk music and dance centre Cecil Sharp House videos of Chicago footwork dancers), asks questions about class, and seeks to imagine something more unified and accessible than the current situation in this country allows for.

The political questions posed by the book also mean a fascinating insight into things like anti-jazz sentiment in occupied Ireland, the citizen-built dancefloors of Lewisham, house music as a coping mechanism for queer people of colour in Chicago, policies like Section 696 in London which underpinned the closure of nightclub spaces. Notably, a section is dedicated to the legendary Plastic People, a Shoreditch club that was foundational to much of London’s present day music culture (Warren notes how it was a starting point for NTS Radio, Hessle Audio, even the beginnings of James Blake’s career, among so many others). In a society where venue closures have become part of the norm – and particularly one where Black music is often venerated and vilified in the same breath – Warren’s documenting of these community spaces and stories is essential so the specifics are not erased (she also holds space for dubstep parties and the more recent euphoria of jazz night Steam Down).

Through the book, she is careful not to overstep beyond her own experience and knowledge. Indeed, instead, Warren’s own experiences are central to this book. She tells the story of herself and her family within their wider context – be that dancing to Top of the Pops as a child in the front room, or the specifics of Ireland’s contentious dance halls around the time her maternal grandmother, Máire, left the country for England. She asks questions about what dancing means through the lens of Britishness, Englishness and, in turn, what those terms even mean. Looking at dances from different regions, she suggests, lends us some insight into identities.

Warren is for the most part deft and light in her writing style. You can feel the giddy feet bouncing off wooden floors, the sly breeze of the Electric Slide (which, she correctly surmises, a generation of people – myself included – have never known as anything but the Candy Dance), the tenderness of a grandfather on his deathbed asking his granddaughter to dance while he passes, the joy of Warren and some peers encouraging schoolchildren in a conga line. And like the dancers – of whom you are now one – you feel compelled, perhaps propelled, to action with each history you read.

Generously and warmly written, Warren’s book encourages us all to unabashedly express ourselves, to feel the rhythm as best we can, and work alongside one another to make sure there are always spaces for us to keep dancing, resisting, and be in community. As she puts it: ‘To dance you must let go of self-consciousness, embarrassment, pride and prejudice, and embrace what you actually have. […] We’re dancers because we’re human and we’re more human – or perhaps more humane – if we dance together, especially when we make it up on the spot.

*

‘Dance Your Way Home’ is out today, published by Faber. Buy a limited signed copy via our Bandcamp, or a standard edition via our bookshop.org page.