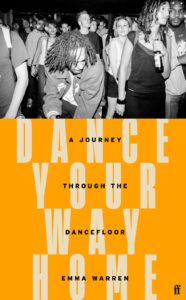

Published by Faber next week, Emma Warren’s ‘Dance Your Way Home: A Journey Through the Dancefloor’ — a book about the kind of ordinary dancing you and I might do in our kitchens when a favourite tune comes on — is our March Book of the Month. Read an extract below.

After The Dance

Dancefloors also exist outside of nightclubs. I had spent much of my teens, twenties and thirties making the most of late-night basements. And while there had been pauses – new parenthood, or in the other lull points that quietly refresh a cultural life – speaker stacks in dark rooms had been a constant. The dancefloor occupied a position that church might have if I’d not lapsed, or football if I’d followed my dad’s side of the family into the hallowed realms of Plymouth Argyle FC. Collective, citizen-built dancefloors are constantly changing, shifting in response to what’s required. People also change throughout their lives, and I needed a new place in which I could move my body. It was time to step off the dancefloor.

Oxleas Woods, on the border of Greenwich and Bexley, offered an alternative. I went there regularly, writing a monthly column about this half-moon of ancient woodland for the crew at nature and culture website Caught by the River. I couldn’t help but see the woods through a nightlife lens. The trees looked like living expressions of the dancefloor, unpolished and uncut. Trunks presented themselves as the source material of the sound-system speaker box. I dreamed up impractical schemes to bring musicians and DJs into the woods as a way of reconnecting the elements. There is music in the woods, too, in the sound of ash tops whispering in the wind, a woodpecker tapping out a beat or a jeep driving past and leaving a dissolving bassline suspended in the air. There’s dancing as well, as birds skim the hedgerows and sweet chestnut branches move moodily from side to side. Eighth century Sufi poet and female Islamic saint, Rabia of Basra, felt the connection divinely, describing trees ‘trying to coax the world to dance.’

The woods were lovely, but it wasn’t enough. I needed other people, and I needed more music. It took a few attempts to find the right location. First, I tried a class at Pineapple Studios in central London. I’d been there once before, in the late 1990s, when publicity averse Detroit techno originators Underground Resistance used it as a location for a press conference. They walked in in a line wearing balaclavas and sat down behind a long desk, answering questions from us one by one.

Dance class in the mid-late 2010s was a very different situation. I wished I’d had a balaclava to hide behind as I struggled to match the teacher’s pop-video moves. Later I took a much more enjoyable class at the studio, but at this point I was the wrong kind of learner at the wrong point in my dance-class journey. I was hyper-sensitive, imagining that people were looking at me and judging me. I was extremely uncomfortable to be so far out of my comfort zone. This was not a dark nightclub; this was a dance studio, with windows through which I could be seen, and mirrors in which I couldn’t help but see myself. I wanted to stamp my foot like a child.

Stamping is a very human response and one which sits at the centre of much movement. ‘There is a dance which contains that stamping of the foot, like the European drum’s primeval beat: the Polish folk dance, the Russian, the Irish, and of course the Spanish flamenco,’ wrote Jola Malin in her book about recovering from terrible grief, Carry a Whisper. The stamp tells us to stop and listen, she writes, because something important is happening: ‘The dancer goes on to tell you – through their dance – of their depth, of anger, sorrow or pain. About being fully alive.’

My friend, poet Kate Ling, encouraged me not to give up. We were walking across Blackheath and we stopped by a tufted mound that is an anomaly on this piece of flat common land in south-east London. The mound is fairly large – it takes a few minutes to walk around it – and it’s covered in broom, gorse bushes and wild-seeded trees. It’s a natural Speaker’s Corner with a rich and rebellious history – Wat Tyler apparently delivered speeches here during the 1381 peasants’ revolt; and by the early 1900s local suffragettes used it for meetings and rallies. Kate and I were sitting on a bench on the edge of the mound, when she told me about a contemporary dance class she’d taken at the Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance in Deptford. ‘There aren’t many places for middle-aged women to take up space,’ she said. ‘And it’s good for middle-aged women to take up space.’

Her words hit home. I went along and immediately loved it. The teacher was funny and accomplished, and Simone, the accompanist, improvised beats on his MPC Live, altering the music to suit our needs and abilities. I didn’t need to exaggerate the emotional content of my moves, as you might imagine in a comic version of the class, in which we’d open like flowers or spill about like rain. My emotional state became very clear to me as I moved, just as emotion is visible in hunched shoulders or an open chest. The movement phrases we built on week by week might contain the suggestion of a feeling – tenderness, or a certain heft – but I couldn’t help but bring myself to it. The phrases became short choreographies that moved us across the diagonals of the studio and they moved us too, shifting sadness or frustration as we laughed and concentrated and approximated our teacher’s fluidity and groove.

However, if sequences of movement are the ‘carriers of the messages emerging from the world of silence’, as Rudolf von Laban believed, then my silent world was expressing that I was terrible at learning dance steps. I spent most of the first year finishing dance phrases facing the opposite direction to everyone else. I turned right when we were supposed to turn left, and I’d have to improvise whole sections in the middle until I could find the steps again, my memory blanking out instructions like an out-of-control delete button. This was extremely annoying, especially given my years of fluency and confidence in the dark corners of a club. I’d stand still, about to practise a phrase we’d just learned, with absolutely no idea of how the phrase started, let alone how it continued. I attempted to learn by speaking the movements into my voicenotes. I tried writing the phrase down in the shorthand we used in class: sweep right, raise arm, shampoo your hair. I asked my teacher if I could video a phrase so I could try to practise at home. Nothing worked. My legs were dyslexic.

*

‘Dance Your Way Home’ is published next Thursday, 16th March. We have a very limited number of signed copies available via our Bandcamp page — order yours here.