Rob St. John gives an insight into the making of the artist’s book, installation film and soundwork produced through his long-term fieldwork and experimentation on the small Finnish Archipelago island of Örö.

The first island residency period took place in January 2016. Öres residents stay in basically-furnished former military houses, the residency format eliminating distance between yourself and the island landscape. Every moment of travel, every sensation, every vista is part of the lived experience of getting to know the place. This daily rhythm facilitated an attentive slowness in method: the time and space to settle in a landscape and attune to its properties. Under a layer of snow and ice, the midwinter island appeared cryptic: military structures and vegetation patterning a landscape of cold grey and muted green, with yellow lichen and red painted cabins the only bursts of colour. Pages of field notes reflect long evening hours researching Finnish words describing midwinter: Tykky (snow on a tree branch); Tykkylumi (snow that builds a dense shell around a tree or object); Kuuraparta (frost beard); Ajolumi (thin powder snow that whirls around); Paukkuva (the popping cold). The routes taken on this first residency were short and circular: out and back in a couple of hours to sites, structures and landforms identified on maps; orientations ordered by the cold.

In turn, this process of island exposure shaped initial creative practices. Towards the northern tip of the island there is a stretch of land barely 100m wide. In the midwinter, the eastern coast of this ‘pinch point’ was frozen: the beach an expanse of patterned ground with interlocking geometric shapes formed by the subsurface uplift of frozen ice lenses; the sea stilled and flat; the horizon dissolving into the mist. Everything was quiet: a camouflaged Lepidoptera trap swung slowly in a tree. The panopticon form and camouflage patterning of the trap echoed the military structures on the island: surveillance logics turning from conflict to conservation.

Walking westward over low heathland pockmarked with military foxholes and tank defences – like microscopic pollen or diatoms blown up to sculptural scale – this stillness opened out into movement. The sea was unfrozen, but its fringes were thick and slushy, causing thousands of tiny stalactites to hang from the boulders where it lapped back and forth. The boulders appeared like frozen jellyfish rising from the sea: their tops covered in snow, their tails trailing between sea and air. These phenomena prompted the questions: where do transitions in material form, ecological growth and atmospheric conditions take place on Örö, and what might they tell us about the island, its histories and futures? How might creative methodologies engage with latent landscape potentials and processes in a seemingly still place?

The midwinter days were short and cold, with less than six hours of light, and temperatures dropping to -20 degrees Celsius. Battery levels in the camera and field recorders fell like the mercury in a thermometer. Standing still for any length of time became an act of tensed bodily performance in itself. Initial filming took place as a process of landscape documentary: at military and geological formations, on ecotonal transitions, towards tangles of human and non-human tracks and traces, with material cycles of decay, on midwinter patterned ground of ice and snow. The rationale for early island explorations was a diffuse process of ‘beating the bounds’ or pacing out the textures and tones of the place.

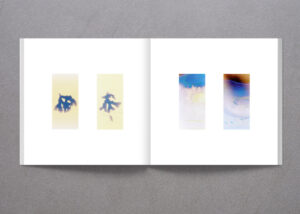

At each filming site a camera was set up on a tripod positioned between chest and waist height. Shots were framed, focused, and then left to unfurl. Dried bladderwrack gently flutters on coiled wire tangled on a lichen-spotted boulder, tiny snowflakes settle on a tuft of sky blue wool caught on a green juniper bush. Looking out from the forest edge, mist washes out the sea horizon below the turning radar tower, reeds move in a slow, frozen dance on a shrinking inlet. Rabbit tracks in the snow echo the outlook eyes of a rusted firing cupola, loops of rusted barbed wire are propped on a forest boulder. Glacial striations criss-cross grey lichen archipelagoes on the granite sea cliffs, star-burst forms of metal coastal tank traps take on the form of modernist land art sculptures. Each period of filming prompted a moment of stillness, a slowing of bodily movement, an attentiveness to the sensory-worlds gusting across the island landscape. With frozen hands and fogged lenses, the filmic exposures themselves were sometimes misattuned: overexposed, badly framed, poorly-focused. Exploring Örö and attuning to its landscape became a process both felt and filmic.

Some of the films had a pronounced and regular rhythm: the movement of waves, the turn of the Lepidoptera trap. Others, however, were largely still, appearing more like restless photographs than cinematic film. These stilled films became thinking spaces: the visual tension between film and photograph highlighting the potential in island formations to take on new trajectories. A mobile gun cover disintegrates into a carved out hollow in the bedrock. Ice accumulates in micro-faultlines. Deer prints, boot prints and tyre tracks criss-cross in the snow. Compared to the films made in the midsummer fieldwork, these clips are inherently exploratory, shaped by atmospheric exposures and the cloak of snow and ice that lay over the island. They document an initial process of learning to be affected by the island; of slowly tracing its various military, ecological, geological and cultural formations.

Very little sound was recorded in the midwinter. This was largely due to atmospheric conditions: batteries in the field recorder drained quickly, inhibiting the possibility of durational recording. However, a few short atmospheric recordings were taken using binaural microphones, alongside brief recordings under the sea ice, using hydrophones. Metal fence wires marking island enclosures were bowed with a violin bow, as were coat peg nails in an empty, disused barracks. These formed the basis for sonic compositions using arpeggiators and tape loops that accompany the midwinter sections of the film. Early island exposures unfurling at glacial pace.

The frozen, still landscape of midwinter had unfurled into midsummer bloom when I returned to Örö in June 2017. Sitting on the back of a quad buggy driving from the harbour to the new residency house on the south-west tip of the island, it was as if the colour, sound and smell of the island landscape had been amplified and brought into focus. Pine and birch woods rippled with an understory sea of green bilberry bushes fringed by wild flowers: red campion, wild pansy, cotton grass. Where the midwinter island was characterised by the white noise of wind, radar tower and sea, the midsummer landscape hummed with the chirruping song of warblers, the morse code clack of woodpeckers and the loop of cuckoo calls. The air was thick with scent: the bloom of rowan, pine resin baking in the hot sun, luminous green pollen drifts from the overstory mingling with the kicked-up dry dust from the cobbled roads.

Where the midwinter landscape appeared cold and cryptic, the midsummer island upwelled with life. Without a curtain of snow and ice drawn across it, the material and atmospheric patterning of the island landscape became quickly apparent: meadow, wood, scrub, boulderfield, burnt heather, heath, beach, military building, rubbish dump, ruin, bog. The island’s visual and felt transitions often seemed to occur over the space of a few feet, pockmarked by ruined structures flecked with a patina of decay. Where the midwinter landscape encouraged brief exposures – short circlings of the residency house limited by light, temperature and battery life – the midsummer landscape prompted an expansiveness of thought and movement. With seemingly endless hours of daylight, I began to cover as much of the island on foot, both to document its ecological, cultural and archaeological heritage and to channel these findings into creative practice.

Walking across Örö’s landscape, the temptation was to stick to well-worn routes: the rough-edged lichen-loop of the coast; the three marked trails opening out along the paths worn by army boots. These routes trace the inverted Y shape of the island, tracking most of the military sites and structures on the island. But on an island of transitions and tensions, emergences and disappearances, it seemed necessary to leave the beaten paths. Transects appeared to offer potential for exploratory research and practice.

Transects are cartographic slices of space and time, lines drawn on a map and followed on foot. The technique is used variously across academic and artistic disciplines to intersect, join with, and tease out patterns of life in landscape survey and depiction. Transects cut across paths, ecotones, structures: they offer new routes, openings and perspectives on a place. Three intersecting lines were drawn on a map of Örö, running north/south, north-east/south-west, and northwest/ south-east. Each transect was followed via GPS coordinates, stopping every one hundred steps. One hundred steps is not the same in every terrain. Linear movement through a landscape alternates variously between expansion and contraction, speeding and slowing, slipping and tripping, climbing and sinking. Distance shrinks and stretches in the ritual of walking a GPS line.

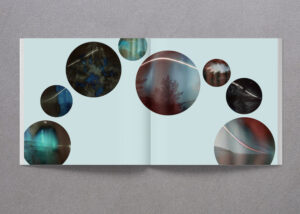

At each stop-point, a GPS reading was taken, plants in the local area were identified, built heritage was described, a single photograph was taken looking straight ahead, and a two-minute sound recording was taken using binaural microphones. In this way, a slow accumulation of sound and image begin to cross-cut the island landscape. Multiple trajectories briefly entwined and fleetly documented, unlikely to ever assemble in the same configuration again. The island transects guided the navigation of unfamiliar terrain away from human (and even, sometimes, non-human) paths. They prompted wading through bogs, picking through the dense understory of old growth pine forest and descending steep granite cliffs, to experience the landscape from new felt and visual perspectives.

Transects encouraged an accumulation of ‘mundane’ Örö landscapes defined by an arbitrary methodology, often at odds with a tourist gaze of the island’s visually striking ruins and natural habitats. A rubbish dump, tangles of scrub, the silt bed of a shrinking lake. In this way, transects helped highlight the material, atmospheric and affective gradients of the island landscape. Such gradients often occurred at ecotonal transitions. Ecotones are spatial boundaries between different ecological assemblages: the abrupt transition from forest to beach, for example, or the gradual shift from felled woodland to regenerative scrubland. Moving across ecotones is a process of navigating patterned ground, in which the sonic, textural, visual and olfactory characteristics of a location can shift significantly over a matter of metres. Attention to ecotonal shifts is therefore always a twinned aesthetic and ecological process.

The island transect walks were aurally documented using binaural microphones. Binaurals make recordings that are seemingly three-dimensional when heard back on headphones: sounds emerge and die away from all sides, above and behind. Binaural recordings can seem immediately grounded in what the recording body hears and experiences of the world. This inherently immersive approach brings its own problems though, not least in trying to minimise loud swallowing, which often records as a submerged ‘glug’. But in this process of attempting to still the recording body for two minutes, a quiet form of attentiveness to the fleeting nature of the aural landscape emerged. This process of stilling prompted new visual documents of the landscape: films and images taken looking straight ahead; fluctuations in light and shadow highlighting subtle patternings of the field of vision. Stilling, in this sense, is a process of skilling.

In the Patterning section of the film, binaural recordings of a thin strip of pine-birch woodland located between the western shoreline and the cobbled military road are mixed with the sonification of the biological fluctuations of a birch tree located close to the island’s radar tower. Fluctuations in electrical impulses across the tree’s leaves – a proxy for photosynthesis dynamics – were converted into the MIDI musical language and sonified. Listening in the field to this emerging sound offered a window into hidden atmospheric worlds. Brief bursts of sunlight caused pulses in the tempo and dynamism of the tree’s biorhythms, whilst the gathering clouds of the evening skies caused a slowing of its musical patterning.

As a result, the sonification of otherwise-unheard more-than-human processes – once brought within audible bounds – fostered a strange, restless musicality. Snatches of melodies that never quite resolve, rhythms that dissolve as soon as they have settled. When gathered in the landscape like this, such recordings remind us of the complex worlds occurring at scales way above and below our human perceptual registers: the tangles of human and non-human life that characterise the island landscape.

*

‘Örö’ is out now on Blackford Hill. More information/copies available here.