Tom Bullough’s ‘Sarn Helen: A Journey through Wales, Past, Present and Future’ was recently published by Granta. A book of heart-aching courage and love and incandescent anger, Pamela Petro wishes she could buy a copy for every person in Wales.

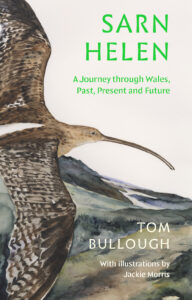

Here’s my quandary: how much can I praise Sarn Helen before you think I’ve been paid by Granta Publications? I assure you, I haven’t been, nor do I know Tom Bullough, so I’ll take a chance. Sarn Helen is as beautiful a narrative as it is necessary; as clear-eyed in its terrifying view of the future as it is erudite in its depictions of the past and the contemporary natural world; as approachable and companionable as it is learned. It is a book of heart-aching courage and love and incandescent anger — not to mention 15 beautiful Jackie Morris paintings of endangered species. If I could buy a copy for everyone in Wales I would. Because I can’t, I will at least write this review.

Sarn Helen is the name of the Roman road — built to pilfer natural resources — that jack-knifes only a few times in its astonishingly straight, 160-mile run from Neath in South Wales to Llandudno in the North. Followign suggestions in bracken in some places, A-roads in others, Tom Bullough walked its expanse in segments during the pandemic for a variety of reasons: to capture the rural and natural reality of Wales in the early 2020s; to investigate traces of the Age of Saints, when holy ascetics faced down any number of natural and supernatural terrors in their huts and caves; and to use the majesty and relative diversity of the present countryside as a yardstick for all we stand to lose in the face of accelerating climate change. Toward that end, Bullough intersperses verbatim conversations with climate scientists throughout his chapters.

At a high point in mid Wales, gazing north to Snowdonia and south to Bannau Brycheiniog, Bullough observes the tenderness of the land at dusk, ‘these shades of green becoming grey; this giant sky with its high, rippled clouds, which in Radnorshire you used to call ‘cruddledy’, curdled.’ And he concludes, ‘It is like watching somebody you love in sleep.’ But he is clear-eyed about the sheep-shorn hills. While recognizing that, for those who live there, ‘they are…the contours by which you are defined,’ he also reminds us that the hills are a ‘wasteland of peat bogs so degraded’ that they give off more than half a million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year — ‘immeasurably’ more than the industries of South Wales combined.

There’s a sobering realization. But what is revolutionary about Sarn Helen is that Bullough follows his on-the-hoof observation with a conversation with Dr Judith Thornton, of the University of Aberystwyth’s Institute of Biology, Environmental and Rural Sciences. The two of them thrash out the thorny problem of what to do with Wales’ sheep if places like Fairborne in North Wales — the first village in Britain expected to be lost to climate change — are to be saved. (Spoiler alert: it’s already too late for Fairborne, and we need to get the sheep off the uplands and pay farmers to restore the peat instead.)

This is just one of Bullough’s observations twinned with discussions. While nothing escapes his eye and ear — ‘Somewhere in the valley a crow is annoyed’ — his sites are ever set on the Big Picture. Prompted by the recollections of elderly farmers, he thinks about the loss of floral and faunal habitat that came with the practice of silage. He has an insightful discussion with hiking partner and author Jay Griffiths about the tonal wrongness of scientists’ and politicians’ dispassionate responses to climate change predictions. He allows the reclaimed land between Harlech Castle and the sea to become a springboard to its inversion, the effect of climate change on sea level rise, and discusses its impact on places like Fairbourne, about which, suggests another of his interlocutors, people need to ‘start to grieve’. But he also looks back at sea level rise in The Mabinogion and how it was related not just to the encroachment of the ocean, but to that of the Otherworld itself.

The past, real and mythic, is not just a reference for Bullough, it’s an inspiration. He comes upon a number of relics from the Age of Saint — Llanelltyd Church, so ancient ‘it would feel wrong to turn on the lights’, founded by St Illtyd in the 5th century — and says, ‘The thing about the Age of Saints is that this was the beginning of Wales.’ Bullough notes that these early Celtic ascetics practiced a richer, more reciprocal relationship with the natural world — as opposed to seeking dominion over it — and that we could do worse now, ‘in the fight of our lives’, to reclaim a similar relationship as we, too, fight devils of our own making.

*

‘Sarn Helen’ is out now, published by Granta.

Pamela Petro is the author of ‘The Long Field’, a memoir rooted deep in the Welsh countryside which is newly published in paperback by Little Toller.