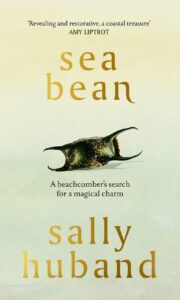

Sally Huband’s ‘Sea Bean’ — a powerful journey of sea and self, trial and hope on the islands of Shetland — is published tomorrow by Hutchinson Heinemann. Kirsteen McNish reviews, finding a book that unites mythology, ecology, the body, and the shifting global horizon. Accompanying photos courtesy of Sally Huband.

‘I am burning to find something new and strange to me…’ — Sally Huband

‘Though I never felt this in words, it reminded me that there was a way out, that there was a way to make my suffering useful. Beautiful even.’ — Melissa Febos

Sally Huband is an extraordinary writer. She is both lyrical and scientific, she weaves and illuminates — a feat of dexterity — to cast an ocean and island spell and show the reader the often stark facts surrounding our seas, marine life and coastlines simultaneously. This is a book of myriad depths that both beguile and soberly arrest you in bleakness and beauty. Sea Bean is both a feminist text and an inclusive one, uniting mythology, ecology, the body, and the shifting global horizon.

If you are one of the hundreds of thousands that are afflicted with an invisible illness that limits how you operate in the world you will perhaps feel seen here. There is a soberness and an evident art in relearning the limits of the cells and sinews that make you up, and in doing so Huband is frank. She respects her new limitations with frustration and sadness and honours the experiences of others who are often neglected and shushed away into what can feel like darkened corners. Kicking back at the walls that could easily have contained her, the totemic shark egg cases she finds on the shore not only sing of loss, but are a timely reminder that she must continue to forge ahead.

We learn within the first chapter this is about a sea change on multiple levels — Huband speaks candidly of the adjustments she must make in her move to Shetland from the mainland, the complexities involved in miscarriage, the fear around sustaining pregnancies, childbirth and subsequent chronic illness and how, once her previous life and career seemed to be cast adrift, she navigates her way through the haar to construct a new way of being.

A line of dead seabirds scattered along the coastline catapults her into action, and she learns to respect the limitations of her body that she no longer recognises alongside the burgeoning realities of climate erosion’s impact on the shores she haunts. Her determination to seek out an elusive Sea Bean is a talismanic quest of her will not to yield to stagnation that instead yields her to hope in the bitter winds of change.

I am reminded of the pleasure of once being gifted Kathleen Jamie’s writing — Huband is learned, honest, and writes with an enviable lack of self-pity however monumental her mental and physical challenges and the extent to which they push her to her brittle edges. One feels she is now seeing thorough a new prism, illuminations that might otherwise have been invisible even to her — the physical pain she endures makes her connection and tenderness with the natural world all the keener. We cannot, if global change is to be made, remain disconnected from “nature” as if it is something separate to human life — insights we could take heed of when thinking about the world outside of our own teaming, changing, unpredictable bodies.

Once arriving in a new landscape, Huband is keen to understand its bones and nervous system; for the new ground to reveal itself to her — but instead of pushing learns to bide her time, determined to understand the ragged fringes of where she has landed to work inwards until her way forward starts to slide into view. In a world that journeys in the main at breakneck speed, and that is often unwilling to take a long view, this account is metered, sensitive and yet hungry. One feels that Huband is rarely still by choice and she is desirous for change — but change that’s considered and enduring.

It would be easy to mistake this book as one of wistful reflections on the tide from its title. Huband avoids over sentimentalisation of the human pull to the sea edge, and never falls into cliché or superfluous prose. She is discerning, justifiably ireful at times, restless, and questing. Her words invigorate, feel rhythmic and relay a clear sincerity and integrity.

The ocean and tides appear her great leveller — she is both churned up and held by the sea and its fathoms — but one feels it’s occupying its edges that is her greatest teacher. A place of seeing and the bringing back to herself, diffusing the ache of her body and psyche. Her newly inflamed bodily seems to have made her peer closer through the skin between what we see and what is submerged and then she brings these findings to us, hypnotic and alluring.

‘The sky is bright blue, but the sea is muddy looking, rich in sediment, and its surface wind torn and white. A cloud of herring gulls billows over the waves. Clumps of sea foam scud against the yellow sand, past oystercatchers that face the wind with hunched and motionless bodies. A few Sanderlings run back and forth as if daring each wave…’

Huband is also readily aware of her own internal contradictions; she pushes herself to loosen the ties of consumerism but is aware she must fight her internal impulse to possess the things she discovers — tiny creatures peered at through jars along with flotsam and jetsam she finds on the beach, whipped up by the tide. She works with ecologists to clear beaches of litter, learns to dissect seabirds to examine plastic intake, and trawls the shoreline post-tide collecting tiny objects, treasuring strange finds that out of context look otherworldly. There is a thrill in casting her messages in glass bottles into the sea, an act of faith and our need for random connection quietly hammering out the ocean’s morse code. Somehow in the face of climate change and the evident need for us to become more responsible with travel, these messages connect us to distinct shores, childhood books, magic, oceanic mythology. It is also the stuff of another’s imprints, thoughts and touch when a kind of dislocation has occurred — in Huband’s case from one’s own body — an affirmative I’m still here. It binds her in that sudden moment to the past, her former self, and the tides and times of sea travel, acknowledging its murky colonial past. Nothing uncomfortable is shirked away from, and more to the point Huband is neither sanctimonious, lofty nor holier than thou, but rather an open-hearted yet discerning realist.

We learn the elusive Sea Bean Huband craves to find has been thought in yesteryears to contain good luck properties and her determination to find one brings her a double-edged sword, including the grim account of innocent island-living women accused of witchcraft — the once benign charm used to calm seas and aid childbirth then turned against the keeper as mark of sorcery. One can feel the emotion when she relays in more recent years, Sea Beans have been presented to survivors of domestic abuse — reclaimed by the women of Shetland centuries after these travesties took place as a symbol of strength to anchor and hold fast to.

There are many beautiful and poignant passages where she connects with others whose lives intersect with hers through the shoreline’s secrets — a wise woman in her chair overlooking the bluster of the ocean completely unruffled by heavy gales; another regaling how as a child she climbed out of her window with her sister to walk precarious jagged clifftops, which lingers long after reading. Huband is a great observer — she is as fascinated with characteristics and the granular detail of people as she is the energies of the shoreline. Her observations are often dreamlike and poetic and capture the essence of someone so much you can almost feel you are stood a few feet away from them.

This book feels important — not only is its author incredibly skilled, but she offers a wider discussion around disability, mental health, motherhood, and how we are as humans no less vulnerable than our counterparts in “the wild”. Perhaps a timely reminder of how you occupy your time out there in the world, and crucially how we adjust our focus towards others outside of our own frames of experience. As Melissa Febos writes in Bodywork of her own biographical writing, it too feels here as if Huband’s writing is ‘an act of resilience’.

This book journeys lightly and buoyantly, and still holds a mirror up to how as women we endure, often silently, invisibly held down Gulliver-like, thwarted by systems designed to contain and control. Most of all, Sea Bean shines like a mirror-flat sea — a message pulses here vibrantly to hold on. The reader, I firmly believe, will find it difficult to not return over and again to its gleaming, wind-torn, keenly felt pages.

*

‘Sea Bean’ is published tomorrow. Buy your copy here (£18.04).