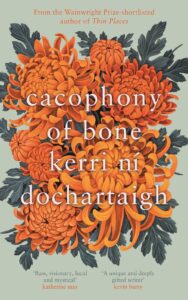

Kerri ní Dochartaigh’s ‘Cacophony of Bone’ — a circular ode to a year, a place, and a love that changed a life — is just-published by Canongate. The author’s wisdom is like water, writes Róisín Á Costello.

Kerri ní Dochartaigh’s second book, Cacophony of Bone begins with an extract from Paula Meehan’s poem ‘The Statue of the Virgin at Granard Speaks’ and the labouring, rushing entry of small bones into cold air as a storm brews over the Northern Irish border. The author slips across the invisible line that separates North and South — ‘a ghost line cutting through’ the heart of the country — as Brexit looms behind her fleeing van and COVID-19 appears on the horizon. ní Dochartaigh and her partner settle in a small railway cottage near Granard and, through the diaristic chapters of her book, she tells the story of a year in deep lockdown, in the deep countryside of Ireland, of making a home and a garden and of trying to decide what her life will look like now.

This book is not about an easy return to earth, a quiet acquiescence to the routines of building a garden and a home, or the easy joy of settled domesticity. It is shot through with the appeal of these things in places, but ní Dochartaigh is more preoccupied with the strange layering of delight and dread that comes with considering time itself. With losing and gaining time to routine, to a pandemic, to the demands of a life which can only sometimes spare the space for writing. A greenhouse of seedlings is destroyed once, twice, by storms. Broadband is elusive. Work gets missed. Loneliness comes in waves. Storms keep her inside, claustrophobia mounting until she is sure she will ‘take to drumming at the bog, like a snipe.’

‘What does it mean to stay put?’ ní Dochartaigh asks, and she is in part asking what it means to choose to stay in one place. To make somewhere thick with memory and meaning. To engage in the labour that requires. But she is also brooding over time itself. What does it mean to be forced to a stop. To remain in a holding pattern, to sculpt time ‘day by day, alone, wandering, again and again, without scale or horizon.’ To stop drinking, to stop dreaming of a life with children, to stop what Sinéad Gleeson calls the ‘spectral longing for another existence. A ghost life…running alongside the one being lived.’

ní Dochartaigh’s home is nestled in the bronnlár, the exact centre, of the country. From her axial point she contemplates the months which move past her. The long arm of the lane that connects her home to the world beyond acts like a clock arm that ticks through the seasons, each month appearing with new birds, new light, new weather. It is a diary of a house as a sundial or, more frequently, a storm dial. Bones and discarded nests appear on the lane, a graveyard of spent time.

Written over the course of lockdown, the book is concerned with the physical act of containment — to a lane, a cottage, a room, a field — but it is also enraptured with the ways time contains our choices, and how our choices will force us to ration time. Beneath the surface of the book run questions about the ways that time, and perhaps only time, can contain grief, can allow love to return, can require us to relinquish the things we love to take up the reins of motherhood, or to relinquish motherhood to hold tight to the things we love already. To accept that none of these things might happen. And to believe that they all could.

Some griefs fade as the year edges on, their ‘steely greys and charcoals water down. I watched the ache for what I did not have turn chalky.’ And yet, these losses cannot fade completely. Deaths from COVID-19 tick upwards, appearing with a predictable regularity as the toll of losses climbs each month and one chapter turns to the next. But time stops when a pine marten crosses ní Dochartaigh’s path; when she finds a nest of cream-white dove’s eggs, broken open and discarded; when a bird enters the house to alight on her pillow. It is a book full of the pristine beauty of ‘creaturely’ objects, things ‘crafted by the careful, repeated movements’ of bodies — a bird’s nest, a badger’s skull, a rat’s pelvic girdle, a gutter full of fledglings, a night-time window furred in moths.

The delight of ní Dochartaigh’s writing is her capacity to measure compassion against observation. She writes with glee and factual appreciation of a ‘pile of fallen branches, a winter pyre of ghost-bark; lichen-limb’ tumbled into the stream that she thinks may be a thin place, before concluding ‘though I beg myself to be done with all of that.’ She describes the potential of the day held in the ‘white-toothed, clenched jaw’ of the morning but also shrugs and asks ‘Who gives a hoot how I spend my mornings.’ In this book, as in ní Dochartaigh’s last, the reader is drawn to her empathy, and her ability to marry it to a shrugging dispassion in a way that shakes the reader from any reverie of reverential self-seriousness.

It is hard to describe what lessons Cacophony of Bone imparts. The more I try to articulate what ní Dochartaigh wants to tell us, the less I am able to. Her wisdom is like water — too strong, and too elusive, to be hooked. After reading it now, several times, I think perhaps this is the book’s power — that it fills the needs of the person who stands before it. It is a story of sobriety, or motherhood, or the choice not to become a mother at all. It is a book about grief, or healing, or the joy of birds, or the frustrations of gardening. It is a book about love, or trying to find the time to write. It is about the strength of community even when we are separated by vast space, and about the importance of proximity. It is about the beauty of a discarded bone, and the importance of always carrying a penknife.

It is a book that creeps into the reader, and asks how we might lock time within us, our bones mapping the lives we lived, trapping the places we have called home in the calcium and carbon of our teeth and bones. Our circles around the sun, our cycling through months measurable in the traces of pollen-infused air, acidic bog water and green proteins that seep into the stuff of us, staking out time’s claim. Maybe that is how we learn to stay put. By absorbing time, by carrying it away with us. By being ‘so caught up in the living of it, I suppose.’

*

‘Cacophony of Bone’ is out now and available here (£16.14).

Róisín Á Costello is a bilingual writer, academic and barrister who lives and works between Dublin and County Clare, Ireland. Her writing has been published in Elsewhere, Caught by the River and Banshee and is forthcoming in the most recent issue of Irish Pages. Róisín has previously been shortlisted for the Bodley Head/Financial Times essay competition and in 2021 was selected as the recipient of a Words Ireland mentorship by Dublin City Council.