Rupert White’s recently published ‘Magic & Modernism: Art from Cornwall in Context’ takes in modern culture, ancient belief systems and much more in between, writes Richard Shillitoe.

Cornwall is defined by its contrasts and contradictions. It is a place of great scenic beauty and post-industrial ravaged landscapes. A place where poverty is never far from wealth. The coast has both sandy bays and rugged grandeur whilst the moors, broken by outcrops of fantastically weathered rock stacks, are the setting for the most intense concentration of megalithic tombs and ritual sites on mainland Britain. Cornwall’s remoteness and its language mould its reputation as a place that is physically and psychologically apart. Geology, geography and culture all lie together in uneasy, shifting relationships.

This is the setting for Rupert White’s new book. He is not a native of Cornwall but he has Cornish ancestry and has lived there for most of his life. Cornwall has entered his soul and his imagination. He has said that this book took nearly ten years to come to fruition. That being the case, it has been a remarkably fructifying decade for him. In addition to his continuing role as editor of artcornwall.org, during that time he has taken over the editorship of The Enquiring Eye: Journal of the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, and written Cornish-related books on subjects as diverse as Monica Sjoo, folk medicine and Tony “Doc” Shiels, all published under his own Antenna imprint.

With this background and the title Magic & Modernism in mind, we can expect a wide-ranging volume that takes in modern culture, ancient belief systems and much more in between. Even so, starting with a preface by Paz Lenchantin, the bassist of the Pixies, and immediately travelling back three hundred years to an account of Alexander Pope decorating his underground grotto in Twickenham with rocks, minerals and gems transported from Cornish mines, it is clear at once that our expectations were probably not set widely enough.

The book has two main purposes. First, to situate the story of art in Cornwall, from roughly 1800 to the conclusion of WWII, within the wider range of internal and external cultural forces acting on the county and second, to show how artists, folklorists and writers contributed to the creation of the modern understanding of the county that we have today — one that has turned Cornwall into a place where the myths, history and scenery attract people in such numbers that they are in the act of destroying the very things that brought them in the first place.

These are ambitious aims for one book. The author sets about them by giving each chapter a separate topic; punctuates the text with explanatory and scene-setting remarks and develops the story by introducing relevant key historical figures. He allows them to speak for themselves by using extensive quotations from their public (and sometimes private) writings. Each chapter is accompanied by contemporary illustrations taken from books, newspapers and postcards. It is a kind of “show, don’t tell” method that works well in bringing the reader close to the primary sources. The constant change of pace and style makes you feel a much more active participant in the unfolding story than usual.

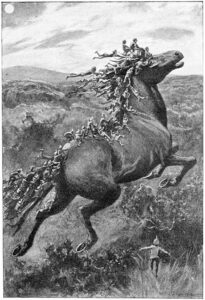

‘Night-riders please stop’ from Enys Tregarthen’s ‘North Cornwall Fairies and Legends’ (1906)

The result is a parade of scholars, creatives, mystics and entrepreneurs. The famous rub shoulders with the infamous and the dreamers with the ambitious. For some, their physical presence in Cornwall was only fleeting, for others it was of much longer duration, but all left a lasting impression. At one extreme, D.H. Lawrence’s time in the county was limited, but Havelock Ellis, the social reformer, whose writings on sexuality are more often referenced than read, turns out to have been a long-term inhabitant. Others who contributed to the culture of Cornwall, albeit in rather different ways, included Frederick Nettleinghame, who successfully monetised folklore by registering Joan the Wad and Jack ‘O’ Lantern as trademarks, and became the centre of an international piskey charm empire.

The visual arts are well represented with due importance being given to the Lamorna, Newlyn and St Ives groups and craft potters such as Bernard Leach. Less well known are the activities of that strange couple, Grace Pailthorpe and Reuben Mednikoff: he a young artist and she a much older psychoanalytically trained former surgeon who viewed each other’s automatically produced paintings as case histories to be analysed, not as art objects to be appreciated on their aesthetic merits.

And, of course, there are the magicians and occultists, among them Aleister Crowley, Mary Butts and Ithell Colquhoun. Colquhoun escaped from London and metropolitan life and in West Penwith, amongst the standing stones, holy wells and suggestive rock formations, fell into the arms of the great Earth Mother and found her true home.

One thing the book makes abundantly clear is that, although it is often convenient to reduce history to the influence of ‘key’ individuals, almost invariably they were part of social and intellectual networks whose influence need to be acknowledged. So, in the chapter that discusses the formation of Cowethas Kelto-Kernuak (the Cornish Celtic Society), the main protagonist is Duncome Jewell, but we are also introduced to the importance of Arthur Quiller-Couch, Aleister Crowley, W.B. Yeats and Kenneth Grahame’s book, The Wind of the Willows.

Overall there is an extraordinary amount of detail, both broad-brush and local colour, but there are some potential downsides to the author’s approach. He is a great fan of Ithell Colquhoun (who isn’t nowadays?). As I was reading this book I was regularly reminded of the feedback given to her by Henry Tonks, her perceptive professor of painting at the Slade School (and, like Rupert White, medically qualified):

The only danger … is that with your active and curious mind you may be led to run after all strange objects. You go out to gather strawberries and come back with two strange beetles and a spider instead.

Much the same could be said of Rupert. Tonks saw it as a weakness in Colquhoun, but in the end it was a strength, enabling her to bring together a diversity of materials (in her case, magic) and relating them in novel and instructive ways. Generally, Rupert’s inquisitiveness enriches the text, but it has its dangers, and one of them is a tendency to over-inclusivity. I would also like to suggest to him that he reassesses his footnote policy. No doubt it is a question of individual taste, but for me there are too many and they are often far too long. Still, for just under £10 you can’t have everything, and so I offer the suggestion to Rupert as a footnote for his next volume.

*

‘Magic & Modernism: Art from Cornwall in Context’ is out now and available here (£9.50). Visit the Antenna website here.

Richard Shillitoe runs www.ithellcolquhoun.co.uk.

Read Stewart Lee’s introduction to the writings of Ithell Colquhoun in our latest archive zine, available here.