Rebecca Smith’s ‘Rural: The Lives of the Working Class Countryside’, recently published by Harper Collins, writes working country lives back into history, finds Nicola Chester.

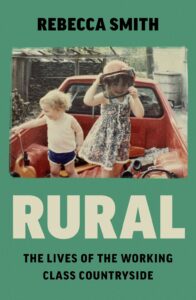

Rural has the most compelling cover: on a background of faded estate-cottage-green livery is a photograph of Rebecca Smith and her brother as small children. They are playing in her father’s pick-up full of chainsaw equipment, with stacked logs – probably ‘estovers’ (wood a family is allowed to take home for their own use) in the background.

It could be a picture of my three (now grown) children. It stirred a deep well of familiar, complex, yearning and contradictory feelings.

Rebecca grew up in tied cottages on country estates — homes that come with a job, where you are tied, body, soul and salary, to your landlord. Her father was a forester and one of their homes, on the Graythwaite Estate in Cumbria, was a single-storey lodge with a turret. It was rumoured to have had the first floor removed, like the top from a Victoria sponge, as it spoilt the view of a previous incumbent of The Big House.

This is a moving, tender and illuminating portrait of a class of people rarely thought about, let alone written about, yet who have shaped the dream of the British countryside that still provides our most basic needs.

Coming from the heart, and with a heart’s knowledge, it is a gentle but thoughtful inquiry emanating from the sensitivity, exposure and vulnerability of a way of life and community not used to speaking out. One that exists in deference to a landowning power and class, and the knowledge that you mustn’t bite the hand that feeds and shelters you. It comes from a place where community is everything.

There is much I recognise. The privilege of living on a grand country estate; of coming home through magnificent gated entrances, and the discomfort of having ‘a boot in both fields’ and a kind of class ambiguity: ‘to fit in with the workers, but also the owner.’

Our children have that inbuilt deference, but also an underlying spirit of rebellion: of wry story and wistful connection to place. It stands in for what they’ve lacked in popular cultural references, growing up ‘in the middle of nowhere.’

But Rural is a book for everyone: we are all of us connected to the countryside one way or another, and it’s full of surprises in what constitutes rural work.

Smith invites us in via family portraits, poignantly intensified from her perspective of a mother of young children and, in the course of the book, carrying and having her third child. Smith’s family were not just foresters, but miners, engineers and mill workers. She makes practical comparisons into these remote-living, tough lives: a great-grandmother living in a hut beside the construction of the Manchester Ship Canal, with 13 children in all and at one point, 11 lodgers to cater for. Shift work meant no let up, and beds that were never empty.

We are only beginning to recognise how many of the places the public love best derive from profits made from colonialism and the slave trade. The Agrarian and Industrial Revolutions were both born in the countryside, and those pretty mill cottages beside picturesque waterfalls fed the urban fashion industry. Looking at the labels on her own children’s clothes, Smith asks if those conditions in our 19th Century factories are comparable to those in Columbia, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh now.

When Smith’s grandfather was advised to retire from his managerial textile job after a second heart attack, the family were threatened with eviction, the firm anxious to hold on to experience. A rapid and successful application for a council house quickly followed.

It’s a familiar and all-pervading precarity. I grew up in Fire Brigade houses when accommodation was still provided for rural key workers. I’ve lived in tied or tenanted cottages ever since; my husband variously a gardener, groom and ‘stallion man’ (always a conversation starter, that one.) A change of career meant the leap to rent an affordable ex-tied cottage. I can see our Big House from my bedroom window.

Rural workers don’t just include farm staff and gamekeepers, they include the community that goes with that set-up — housekeepers, bar workers, hairdressers and teachers, carers, plumbers and, in our case now, paramedics and school librarians. Often, it’s the ‘scattiness,’ as writer Jeni Bell calls it, of piece work and part-time jobs done by women that define that rural work.

Rural is a timely and prescient book. Gentler than Natasha Carthew’s (justifiably) angry Undercurrent (her Cornish rural working class memoir) it laments the same ebbing away of life and community from the countryside. Tourism is important, but it has become all-consuming; devouring the very things it has been attracted by. In our village, houses are shamelessly advertised at impossible prices, ‘for that dream move to the country or the ideal weekend retreat.’ Smith’s former Cumbrian estate offers ‘luxury holiday cottages and magnificent views from a hot tub.’

The message is as clear as it was in those outrageous-but-true stories of Lord such-and-such moving whole villages because they spoiled the view: you can create the countryside, but you cannot live here, retire, return or raise your children here — and if you do manage that, they cannot come home.

As Smith states, ‘we need preservation and progress, environment and economy, locals and incomers.’

Rural is a personal and involving elegy to those tied, tenanted and tenacious communities who shape and have shaped our landscape and lives, yet remain excluded from it. Smith writes those working country lives back into history with great warmth: and gives them a place to dwell.

*

‘Rural: The Lives of the Working Class Countryside’ is out now and available here (£18.04).

Nicola Chester is the author of ‘On Gallows Down: Place, Protest and Belonging’. You can follow her on Twitter here.