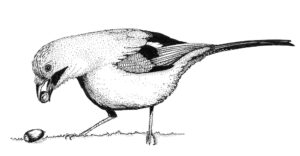

Recently published by Granta, ‘Nature’s Calendar: The British Year in 72 Seasons’ divides the year into segments of four to five days, inspired by a traditional Japanese calendar. In the edited extract below, Kiera Chapman delights in the uneaten jay snacks that grow into forests. With illustrations by Rebecca Warren.

18–22 October

Acorn-caching, Forest-planting Jays

I don’t remember ever seeing as many acorns as I did in the autumn of 2020. Once every five to ten years, in response to cues that we don’t yet understand, oak trees synchronise to produce a bumper crop of nuts, a phenomenon called a ‘mast year’. So plentiful were they that the ancient oak woodland near my home had a thick, crunchy russet carpet for several weeks.

These were fat days for the local wildlife; not even the greediest grey squirrel could gobble them all up.

However, the following autumn, the oaks had a far leaner year, producing only a few acorns. With this sudden dip in their food the jays in my area seemed to change character. Usually shy woodland birds, they began to venture into domestic gardens, fighting the resident magpies and crows for a replacement food: peanuts.

Jays are ecosystem engineers. From September onwards they collect thousands of food items for the winter, with acorns a particular favourite. They prefer larger nuts, and can carry five of them at a time: four in an adapted gullet in their throats and one in their beaks. This precious cargo is then cached, often by burying it in the ground in open areas with loose soil where the food will be safe from mice.

These birds have great spatial memory: they probably use landmarks like bushes and rocks to remember where their caches are located, and will return year-round to grab a snack. Nevertheless some of the acorns go uneaten, meaning that the jays have effectively planted them. Assisted by the fact that there is a dip in the adult jay’s consumption of acorns from April to August, these neglected acorns will produce a crop of fresh oak seedlings to regenerate the forest the next spring.

If you’re walking in woodland, you may well hear the raucous wheeze of a jay before you see it. However, you may also hear a jay making more unusual sounds. These birds are notoriously good mimics of other species, able to do a startlingly accurate impression of a whole range of noises.

In his essay on animal intelligence, Plutarch tells the story of a barber in Rome who trained a jay to reproduce not only animal cries but human speech. When a wealthy man was buried in the neighbourhood, to the fanfare of many trumpets, the jay fell completely silent, and stopped asking her keeper for food or water. Passers-by wondered if she had been deafened by the music, or even poisoned by a jealous rival bird trainer.

However, the jay was actually refitting her voice to imitate trumpets, and soon burst forth into a perfect imitation of the instrument, to the wonder of onlooking crowds. For Plutarch, the story offers an example of a non-human creature using self-discipline in a way that implies a rational and self-directed will to learn. Though this interpretation is dubious, the jay’s modern Latin name nonetheless reflects both its vocal abilities and its favourite food: Garrulus glandarius, the chatterbox lover of acorns.

*

‘Nature’s Calendar: The British Year in 72 Seasons’ by Kiera Chapman, Rowan Jaines, Lulah Ellender and Rebecca Warren is out now and available here (£14.24).