Collating the writing and art of one of the most prolific wood engravers of the 1930s, ‘Clare Leighton’s Rural Life’ — which reflects the artist’s lifelong fascination with the virtues of the countryside and the people who worked the land — is published this month by Bodleian Library Publishing. This beautiful anthology is also our Book of the Month for October. Read a seasonal extract, taken from the ‘October’ section of ‘Four Hedges’, below.

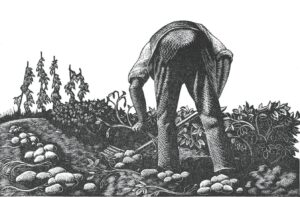

Digging potatoes

Our potato crop waits to be dug. As I fork up a root and scrape a potato with my fingernail the skin slips off. All around us work shouts to be done. We have no time now for quiet enjoyment of our garden, for the first frosts and the autumn rains will soon be upon us, checking our digging and planting.

We enjoy digging our potatoes. It is the big treasure hunt of the year, even more exciting than searching for the fruit in the tangle of straw round the strawberry plants. The excitement lies in the anticipation we feel each time we stick the fork into the ground. How many potatoes will there be beneath this plant? This anticipation never tires, even after rows of digging. Here is all the mystery of an unknown, invisible harvest. We can see the extent of our peas and beans, and we know that each green-leafed parsnip top will have a corresponding root below, but who can tell how many potatoes huddle beneath the plant that we see above the ground?

As my fork brings up the cool, moist potatoes, I lay them out in the sun to dry. They look beautiful as they lie on the earth in creamy rows. The limp, fading haulms curve away from them by their side in regular lines. Minute, undeveloped potatoes cling to the tendril roots of the plants, smooth of skin and fresh of colour in contrast with the decay of the aged seed potato.

A robin sits near us on the haft of a spade and sings his autumn song to the worms that I unearth; they are many, and they wriggle back below the soil as fast as they can. But the robin is too quick for most of them, and he has a great feast. From time to time my fork spears a potato; in its damaged centre I find lovely small pink worms coiled tightly round. Annie and the gardener do not share my enthusiasm over the beauty of these worms. They tell me that we should have dug our potatoes earlier as sensible people have done. The damaged potatoes will not keep.

Digging exposes an independent living world below the surface of the earth. Among the persisting roots of bindweed is the home of the burnt-coloured brittle wireworm; here it will live for nearly six years before it escapes above the soil as the click beetle. The little woodlouse wanders about, ready to coil itself into a ball at the slightest vibration. The centipede twists its body until it is the shape of a switchback at a fun fair. Rubble and bits of broken crockery speak to us of men who knew this field before our day. But it is a world that finds us back in time and makes of the clods we turn pages of history, for one day among the marigolds we dug up a local money token of the eighteenth century. Relics of Roman Britain are scattered among our earth as broken pieces of brick; they are many for we are on the edge of the Icknield Way, which was used as a Roman road. Our imagination one day was especially excited by the finding of the tooth of a wild boar. Instantly our garden seemed full of perils, and civilization shrank to a thin veneer of three inches of chalky soil. We have kept the tooth, and when life grows too respectable and secure, a glance at it reassures us with a thrill of fear.

*

‘Clare Leighton’s Rural Life’, edited with an introduction by David Leighton, is out on 19th October (£30, Bodleian Library Publishing). Pre-order your copy here.