Mark Mattock’s latest cabin missive is sprinkled with star dust and flecked with magma.

November: Veneration.

‘Cause none of them can stop the time’

– Bob Marley, ‘Redemption Song’

It may not have been noticeable, had there been anyone with me, but my inside just violently tried to jump out of my outside, as I turned off the tap I’d left running, at the sight of a very large male house spider marooned on the wretched turquoise sponge caught twirling in the whirlpool above the metal sink’s plug hole. There’s always one. I didn’t see this one. The cabin is perfect tegenaria domestica habitat. They’re responsible for all the mouse droppings in the corners, which are actually the hollowed out husks of the woodlice they mostly feed on, culling them in substantial numbers. Pest control. It’s the autumn mating season and the sink’s regular detainees are mostly smaller bodied males that have been ‘out on the pull.’ It is actually they that are being ‘pulled’ though. Wandering males with their swollen, sperm-soaked palps like bouquets on offer, hopefully looking to be lured to a virgin female’s pheromone-soaked silk bed sheets. Successful invitees are often kept waiting, at the risk of being misinterpreted and eaten, in a corner of the bed until she’s ready to ‘change into something more comfortable’ — her final moult into sexual maturity. I rescue the frustrated castaway from spinning sponge island, put him on the window sill, wish him good luck and hope his palps will still impress, and that there is a female still patiently waiting in some silky woodlouse ‘baubled’ corner.

Crystalline dawn stillness made vivid by a rehearsing robin. Not a single leaf, nor blade, moving. Glinting minute gossamer necklaces. Sparkling miniature chandeliers of delicate grass seed heads, poised on the thinnest stems, shatter and crash when a slurred buzzing hornet bumps into them like a staggering drunk into lamp posts.

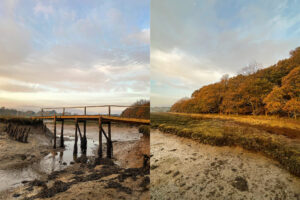

Through binoculars I watch, transfixed, the impossibly slow, delicate, incremental enveloping of a tiny mud islet in the middle of the flooding rivulet; by a single molecule thick membraned rim of surface tension, pushed by a whole ocean, pulled by celestial bodies. A force totally unstoppable. The same force measurable in the morning cup of coffee still steaming. The sheer imagination-exploding enormity of it all condensed into a simple observation. Tide watching is star gazing. Just a little over from where the islet of mud submerged without trace, bubbles rise from a very specific point, with mechanical regularity, as a crab tunnel fills. Hitting the surface they’re held on the ultra thin slick of microbial scum and then steadily, uniformly, threaded onto an invisible string as the water passes over the rising column. The long string of pearl bubbles drifts unbroken all the way to the footbridge, before being pulled apart in a swirling eddy and scattered in all directions. The kingfisher peeps a warning of his imminent arrival, followed immediately by repeated peeps of a hotly pursuing other. Just enough time to look up as the little avian jet fighters rip arrow-straight through the gap between the bladder wrack-skirted uprights. Last winter’s territorial war between the two has obviously resumed. A lanky greenshank is deftly snipping, pinching off, the spiky hinged appendages from a small crab, repeatedly dropping and picking it up with its ever so slightly upturned chopstick bill. It dips it in water to clear the mud before the first attempt to swallow it. More dismemberment required before a successful second attempt. Satisfied it nods before exploding off over the water with a three-peep call.

A fairy ring of sodden wood pigeon breast plumage glows luminescent in the dark of the dusk lane. The rapacious ferocity that made it long doused, with the feathers, under a cling film of heavy dew. It’s probably a kill made yesterday but in the damp silvan calm it feels like the faint odourant of hawk and adrenaline still lingers. Normally I’d be surrounded by the pitter patter and wheezing whistles of dozens of fattened up pheasants, stepping cautiously, suspiciously, through undergrowth. Still hanging around the pens they were reared in, hidden in the spinneys either side. Their blue plastic lunar-landing-module looking feeder barrels spaced along the path every hundred meters. But the small shooting syndicate that rents the space failed in their licence application. Having had to obtain one for the first time due to recently introduced legislation, requiring one if you want to release pheasants in or within 550 meters of a designated SPA (Specially Protected Area). Which here is the estuary river and salt marsh.

The toasted oak canopy is beginning to bald. On the big marsh-facing boles — and the jetty slats — duck egg green doilies of green shield lichen are re-saturating, softening back to wrinkled winter chamois cloth in the increased moisture and cooler temperatures; like fresh velvet on the antlers of the fallow bucks. The bracken fronds anaemic yellow, rusting at the edges. Like some old car in a forgotten village tip. Charred shrivelled blackberries with pale specks of seed still clinging at the ends of dangling wires as if caught in a recent fire. In which sagging orb webs glisten, the pale fat swollen abdomens of the spinners tucked up in the black carbonised fruit, waiting.

Another fresh morning. Replenishing wood stock and keeping warm by dragging the earmarked heavy boughs of oak, that have been laying around like the giant shed antlers of some huge prehistoric forest ruminants, back to the cabin. As the new log pile stash accumulates by the wood burner so does the number of various multi legged arthropods fleeing as it builds; skidding and scuttling across the the lino floor towards dark corners like commuters in the concourse in a major tube station. Mostly woodlice, but also spiders (three species), earwigs, a centipede and a small black beetle. More drop out at every heavy knock along with dust and debris: woodlouse shit, bits of exoskeleton, arthropod cuticle, strands of dry fungal mycelium. Compost! Smells good, like a scented candle of mulch, must, earth, oak; a bit sour, taint of piss and vanilla.

The first fire of winter. Rite of seasonal passage. Ritual. As if there is only one precious saved match left. Everything prepared meticulously. The burner thoroughly brushed clean. Placing the initial loose ball of wood shavings. Shaved yesterday and kept in anticipation in my pocket along with the match box to make sure of dryness. Topped with thin splinters. Around all of which a scaffold tower of kindling. Then roofed with a few splits of log. Striking the match with all the tension of a first kiss. It bursts into phosphoric fury. Then it’s guided to the shavings before the tiny violent chemical reaction reduces to a single delicate flame. Two gentle touches and a small orange glow builds at the foot of the devotional offerings. Hot pain as the little flame carbonises the match stick and licks my finger. I take a long deep breath and begin resuscitating the cast iron lung. Leaning into it and exhaling steadily and continuously. The flames welcome my air, rapidly climb the scaffold, become noisy; I feel the first blasts and prickles of the exploding kindling against my face. Leaning back as the flue takes over, sucking oxygen through the burner, the flames now fierce and roaring. I swing the door shut, adjust the air flow. Soon the hearth surround ticks and cracks as the temperature rises, the heart of the cabin beating once again, supplanting the heat of the summer’s sun. I remain kneeling in worship. Don’t get me wrong, I have a gas cooker, it’s not some ‘survival’ trip, not quite!

Just a simple act of veneration.

I wake to the cabin glowing faintly orange. Definitely not the dying embers in the wood burner, it’s not big enough to last fourteen hours of dark. It’s otherworldly, as if from a distant source, a giant distant forest blaze, an erupting volcano. Something spectacular is developing. Something rare. I quickly make a coffee and walk out to the jetty, into an eerily beautiful apocalyptic pre-dawn glow. The sky is burning, the mudscape a molten lava field into which hot flowing magma cuts a rivulet and I’m shivering, frozen and awestruck. Morning is breaking like a first morning. And yes, a blackbird is chinking away somewhere behind me. My phone camera can’t deal with it, sensory overload, garish files. The whole scene looking like an elaborate giant backdrop canvas for some sci-fi epic. I tweak and fiddle with the soft ware for capture after capture until the burning orb finally breaks the distant tree line to the right of the tall protruding Wellingtonia.

The rest of the morning lazy, watching flotillas, rafts and murmurations of winter wildfowl: teal, wigeon, mallards and brent geese. And waders: peewits, curlews, redshanks, and those to far to identify. All sporadically harassed by the marsh harrier and a recently arrived tiercel (male peregrine), the marsh, for both, ideal winter hunting grounds.

As the afternoon sun arches across the canopy a transient sequence of golden illumination moves through the understory dim. Fleeting incidence beamed and sheared as the toasted brown oak crowns sway. The last big yellow ovate leaves cling on to the spindly tips of hazel, flapping gently like golden prayer flags. Already, stiff little lambs tails and new buds.

I duck, suddenly, involuntarily releasing some weird vocalisation. Something wings, feathers, in the millisecond retinal afterglow. Waft and wake of softness. Looking up I catch a glimpse of the fleeing tawny owl vanishing as if into thin air. It exploded, without a sound, from the deep gash running the full length of the old cracked-bark beech bole where it had obviously been roosting the day away. I’m inching my way along the steep bank up from the long sweeping bend in the main river where the oyster beds lie. (The whole estuary shore is strictly off limits). Apart from the odd items of lurid boat plastic blown up from the river tide line there are no other signs of human spoor. From outside, even from a short distance, it’s a classic crescent bank of mature oak. It’s the understory that’s incredible. A near impenetrable steep sloping tangled terrain of hawthorn, blackthorn and bramble. Between which mycelial web like paths thread through the leaf litter. Deer tracks: fallow, roe and muntjac. Impossible to navigate upright, progress is a back-aching choreography of dips, bows, crouches and lurches. Through lethally spiked bushes, tough springy thigh-whacking saplings, ripping skeins of barbed briar trip-wires, snares of honeysuckle, scalp-scraping knots and burrs; deep sodden gullies and knee deep swamp patches. All for a few hedgehog mushrooms and blewits. Later while the pasta saucepan simmers I study the sketches of the ‘wildwood:’ scratched in blood and red specked stitching on my pale candle white shins and hazel-stain hands, picking out the splinters with dirt-wedged finger nails.

The canopy is now nearly bare. It’s light around the cabin again, lessening the heavy gloom. Out front the ground has been crudely ploughed up. Gored by the rutting fallow buck whilst I was away. The morning materialises shadowless, muffled, flat, leached of colour. Featureless monotone grey sky. Distant oak banks rinsed of features, diffused by cold slanting drizzle. Morning isn’t breaking, it’s looming; again. Out collecting more wood. Everywhere columns of trooping funnels, AKA Monk’s heads, and huge arches of clouded agarics spread over the leaf litter, good eating but, like blewits, they upset my guts a bit. I assist the dried out puffballs with spore dispersal by little foot taps. In the clearing adjacent to the holly grove, strange spurts, puffs, of leaves, a bit like the water spouts spat by the clams when staring out across the mud. It inexplicably looks like some huge invisible acorns are falling from the canopy. A cock blackbird enters the scene from the holly grove and starts bouncing and rummaging through the leaf litter throwing leaves about. Causing exactly the same disturbance! Redwings, it’s a flock of redwings, so camouflaged in the litter, in the deep dull, they are invisible. Realising, I now make out their white-striped eyebrows. The leaves were miming the foraging thrushes. Suddenly a blue tit hawk alarm goes out a fraction before a big explosion in the leaves, surrounded by a cluster of smaller ones, with the loud stuttering staccato shrieks of the fleeing blackbird. I don’t actually see the the projectile that caused it. By ear I follow the terror-stuck blackbird’s panic calls through the confusion of hawthorn, hazel and holly alongside me, I feel the translucent phantasm of powerfully winged energy hounding it. As if the female sparrowhawk is made of glass, only the ghostly white under her tail rump intermittently visible. I think the blackbird escapes. The hawk passes moments later, along the path, empty taloned.

The last day of November. Freezing morning. My breath, as if I’m hitting a bong, steaming up my glasses. Outside it’s snowing oblique gusts of freeze-dried leaves. Then between each blast leaves just drop vertically in no hurry at all. I can hear raven in the dimensionless grey over the marsh. The heavy Cronk muted by the incessant mizzle. A surrounding hiss, a white noise, builds, amplified by the last crisp leaves still clinging. The deck is suddenly being salted. It’s snow; sharp, biting, ultra fine snow. I swear I’m seeing stars. I slide the glass front open and step out. I put my reading glasses on and fall to my knees. I am seeing stars. The snow is falling in single large crystals, or small multiples that break apart on hitting the deck. Billions and billions of hexagonal plates and stars, stellar dendrites of water vapour, no two the same. Stars are falling from the sky.

I’m literally being sprinkled with star dust.

*

Mark Mattock. Artist. Photographer. Publisher. Rabbit Fighter. @the_rabbit_fighters_club