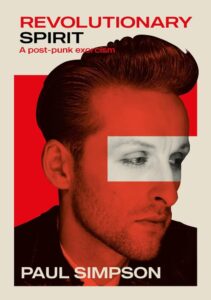

The Teardrop Explodes co-founder & The Wild Swans frontman Paul Simpson’s ‘Revolutionary Spirit: A post-punk exorcism’, is published today by Jawbone Press. Read an extract below.

October 2011. Wester Ross. The six-hundred-mile drive from Liverpool to Kyle of Lochalsh on the west coast of Scotland is a killer. Four hours into the journey, with the outskirts of Glasgow in the car’s rearview mirror, my accelerator foot begins to ache and my seat feels like it’s made from Highland Toffee. Surely our destination must be close by now? As the crow flies, it almost is, but the serpentine roads around the loch and over and between mountain and glen mean that, depending on the weather conditions, I still have another four or five hours of clutch-depressing, gear-changing, high-concentration driving still to go.

I’ve been doing this road trip in the second week of October with my family for twelve years now, so I should be used to it, yet every year, somewhere around Culloden, the physical and mental toll of such an epic drive, amplified by the psychic weight of the landscape, still manages to catch me unawares. Exhausting as the journey is, the tapestry-coloured hillsides, Victorian train viaducts,1930s wooden telephone posts pitched at expressionist angles, and the sheer Shakespearean drama of it all make it spectacularly worth it. This year, my Spot The Roadkill prize winner is found on the A830 near Lochailort: a ten-pointer stag with one entire haunch sawn off by a passing opportunist.

Located on the banks of a secluded bay on the south shore of Loch Carron—one of the most unspoiled and beautiful areas in the British Isles—the two cottages we three families share at autumn half-term are so inaccessible that they can’t quite be reached by car. Unloading our many bags of supplies on the hillside by a raging burn, we carry them across a railway track and a field of nervously bleating and defecating sheep. Arriving in the late afternoon with perhaps just a half-hour of daylight remaining, our fellow Liverpudlian friends of thirty years—Mike and Jeanette Badger and their kids, Amber and Ray—are already here, and the lovely Walker family, driving up from their home in Manchester, have texted us en route to inform us they’ll be late as they are still in Fort William, stocking up on supplies.

I’ve been itching to get out upon the loch since this time last year, and it’s all I’ve been thinking about for the past hour. A fortnight ago, I drove all the way to the Black Country to collect this Canadian-style kayak, and I’m impatient to try it out. Novice that I am, I’ve also bought a retro-looking but insubstantial Norwegian life-jacket more suited to aiding someone falling into a canal than a tidal sea loch. Unwilling to wait until morning, and filled with the designated driver’s sense of entitlement, I ignore the pleas to relax and have a restorative cuppa and set out for a twenty-minute ‘paddle around the island’ before it gets dark.

—

Allegedly the inspiration for Neverland in J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, Eilean na Creag Duibhe, or Heron Island, is a Scots-pine-covered heron sanctuary that rises out of Loch Carron some one hundred yards in front of the cottage. On spring tides you can walk out to it upon a narrow strand, but right now the tide is on the ebb. Pushing off from the shore, I steer the kayak’s nose out through the sweet-smelling, ochre-coloured kelp close to shore and head out into clear water. Jumping in and settled into the seat, the first arc of my paddle startles a cormorant from off his rocky perch on the island’s promontory and into panicky, low-level flight.

Paddling with the outgoing tide is easy at first, the water offering little resistance to the blades. Close to shore, the water is so clean that even at a depth of six metres I can look over the side and read the loch bed in detail. Pale cream sand overlaid with saltwater flame shells, starfish, broken coral, and the local grey mussels known as Clappy-Doos. On my first visit to the area in 1996, I nearly choked when one became lodged halfway down my throat.

With Ulluva, the small rocky outcrop and seal haven to my back, I paddle anticlockwise around the perimeter of the island and into the deep waters in the centre of the channel. In doing so, I’ve already passed the point where, in previous years, using a borrowed kayak, I’d felt I’d left my comfort zone; but this being my kayak’s maiden voyage, I feel like a modest adventure. With Kishorn to starboard, I am now half a mile equidistant from the shore on the narrowest sides of the loch, so I stop paddling and allow the outgoing tide to gently nose the kayak around.

The centre of the loch affords me a 360-degree view of the landscape. From the lunar barrenness of the Isle of Skye to distant tree-covered Applecross, from the castle ruins at Strome to Glenelg, it is all, uniformly, achingly glorious. The beauty is so extreme, the quality of light so remarkable, the wildlife so abundant, it’s simply too much information to process. The only way to filter all this magnificence is to stop looking for single ‘events’ and widen one’s focus to envelop the whole.

Autumn on the west coast of the Scottish Highlands is never less than astonishing, particularly during October, when the mercury dips and the shortening days trigger a chemical change in the flora. Nature’s grand reveal isn’t June or August but now, in its last exhilarating burn before the sleep of winter. This is no electricity-pylons-in-fog, raincoat-and-fag-smoke English autumn of regret; it’s celebratory, easily the most exquisite firework in the box. From June to Christmas 1996, my wife and I lived in a remote cottage in a horseshoe-shaped glen not far from here. Formerly owned by the Forestry Commission, the cottage was as damp as it was charming, its whisky-coloured tap water fed by a tumbling burn running straight off the mountain. Marooned alone without a car for the first month, I walked the surrounding forest and found that the landscape awakened something in me—some dormant Celtic, Simpson-forebears thing. We didn’t know it until the following spring, back in Liverpool, but my wife become pregnant while here, and that, combined with the warmth of the locals, brought us back with our young son, to rewild here each autumn with friends.

The current is already stronger than I’d anticipated, and although I can’t see it yet, I can feel the hull beneath me being gently guided in the direction of Plockton Harbour, famous for its use as a location in The Wicker Man. My plan is to potter up and down for a bit, get a feel for the kayak, and then, before the tide gets too strong, I’ll break from the current and row toward the shore by Duncraig Station. Once in shallower water, where the pull is weakest, I’ll about-face and head back home, slowly hugging the coast.

Before I can attempt this, I become aware of a vast shadow falling across the hillsides. Within seconds, the light fails, and the colour entirely drains from the landscape. An extraordinary cloud formation is developing across the ridge of Precambrian Munros and the mountains that comprise the Five Sisters of Kintail. It’s a downward nimbostratus; a colossus that spreads vertically at astonishing speed, pouring down the sides of the three-thousand-metre-high Sisters and surrounding braes like dry ice cascading from the lip of a bowl. My God! It’s Wagnerian! Gathering mass, it obscures the Bealach na Bà, or ‘Pass of the Cattle’, at over two thousand feet one of the highest roads in the British Isles. Down it tumbles, a roiling ghost avalanche that swallows up hectares of pine forest in moments. Reaching sea level, it haemorrhages out across Loch Carron toward me, soon enveloping me in a John Carpenter-esque fog. It’s as if the sky has collapsed.

Floating in a whiteout now, I can just make out the kayak’s prow and the blades of the double-ended aluminium paddle laid across my knees. Turning my head, I can see the stern but nothing beyond. This is the stuff of dreams, possibly nightmares. The closest I’ve come to experiencing something as disorientating as this was back in the mid-1980s when I encountered an ‘infinity cove’ in the photographic studio of Andy Catlin, while he was shooting images for The Wild Swans’ Bringing Home The Ashes. The infinity cove is a smooth, white-painted wall that curves out on its top, bottom, and sides. Looking into it, this cyclorama tricks the eye into thinking there is an infinite distance in front of you that you could be facing any way up, even floating in space; whereas, in reality, you can just reach out and touch its walls.

Disorientating and beautiful, the difference out here on this two-mile- deep loch is the risk to life. The North Atlantic water is cold, and my waterproof army poncho runs with atomised mist on the outside and condensation on the inside. Seated in the kayak, hair plastered to my face, my range of vision is down to just a metre in any direction. Lost in fog, drifting on an outgoing tide, am I in actual physical danger here? I think I might be. What is this huge rock outcrop looming to port? It can only be Sgeir Bhuidhe, the ‘yellow skerry’ offshore near Duncraig—but, if it is, then shouldn’t I be passing between it and the mainland? It should be on my starboard side, which must mean I’ve drifted a lot further from shore and safety than I’d realised.

I’m being pulled backwards now, caught in the outgoing tide. This isn’t good. If I am lucky, I’ll end up somewhere in the outer reaches of Plockton Harbour; if not, I’ll be channelled past the decommissioned lighthouse on Eilean a’ Chait and into the Inner Sound. Beyond that are the measureless depths of The Minch—the deepest water on the continental shelf; waters so impossibly deep that the Royal Navy use it to perform their submarine sea trials.

What was I thinking coming out on a sea lock when tired and ill- equipped? And why was I so impatient to get out onto the loch as darkness was falling, rather than waiting for morning? I don’t have a phone with me, and even if I did there’d be no signal out here. In October seawater this cold, swimming is not an option. As if this weren’t disturbing enough, something large and sleek in the water below skims the fabric of the kayak’s hull, causing it to lurch horribly. The inertia turns my stomach. It’s too big for an otter, so it can only be a seal, toying with the unfamiliar shape floating above it.

I’m not absolutely sure, but through a gap in the fog, I thought I just glimpsed an area of unstressed water between the running narrows. Paddling carefully, I find it and manoeuvre inside it. Miraculously, my momentum is halted. Why is it here, and how is it possible?

Gasping in panicky lungsful of chilled air, I consider my options.

1. I can row in any random direction, praying that I won’t hit a rock and capsize—maybe I’ll get lucky, avoid the swift running narrows out to open sea, and make landfall on the opposite shore to Duncraig, or

2. I can sit off here in this miraculously calm pocket of water and wait for the situation to change for good or ill.

The former feels akin to playing Russian roulette, the latter head-in-sand madness. I thought I had experienced fear before, but the reality is, I haven’t. I’ve had to fight my way out of ugly situations before—particularly in the late 1970s and early 80s, when just having a weird haircut or the wrong clothes was enough to get me jumped. In those situations, the fight- or-flight response would kick in, but there’s no discernible adrenaline rush now, presumably because my brain knows that it wouldn’t serve me in this situation. There is no right choice right now. It’s like I’ve been absolved of any responsibility for my fate.

Against all logic, it’s now, suspended inert in this moon-coloured soup, that the fear and desperation I’ve been battling to suppress this past half-hour or so is overwritten by an ineffable sensation of stillness and calm. It’s as though a soft cloak has been draped about me by an unseen hand. I have the sensation that I no longer exist in physical form but in something closer to dream consciousness. Divine experience or divine madness, a subliminal and benign presence is here with me, and it feels better than any drug I’ve ever tried or had administered. Am I closing down? Experiencing some natural mental and physical anaesthesia before I succumb to hypothermia and eventual drowning? Is this the body’s intuitive coping strategy, or am I, as I’m inching toward believing, trespassing in sacred space, floating within some nautical version of R.S. Thomas’s ‘Bright Field’?

If I am dying, I honestly don’t care right now, because I’m in the phosphorescent womb—the aevum—the sphere of the soul. Is this why Byron swam the Bosporus? Why free divers risk narcosis? To access the holy narcotic? I have no idea how long I’ve been out, both on the loch and lost in eternity. It could be an hour, it could be ten thousand years.

Like a miracle, just as I feel the sickening inertia of the current’s pull upon the hull beneath me, a breeze blows and begins to disperse the fog, skein by gauzy skein. There’s a waxing moon up there somewhere, and between the retreating whorls of mist I can see silvered threads of water running off the hills, and, long distant, the glint of wet roof tiles of Duncraig castle. In its way, the fog has protected me. Had I been able to see just how far away from land and safety I’ve drifted, how close to the Crowlin Islands I am, I’d surely have panicked and possibly made the disastrous mistake of paddling for the closest shore—and thereby meeting the invisible channel that could drag me out to sea.

Paddling against the outgoing tide is hard enough, and my back and arms ache horribly, but having the landmark of the Castle to aim for, I fight for my deliverance. Over the next fifteen to twenty minutes, I make slow but steady progress, the mist retreating into pockets and folds in the hills. Spotting a distant pinprick of warm light, my heart surges. If I am right, it’s a lantern burning in the larger of the two cottages’ window. But, if so, why is Arnold Bocklin’s The Isle Of The Dead looming out of the darkness immediately ahead of me?

Quickly reverse-paddling so as not to puncture the kayak’s skin on the barnacled rocks ahead, I manoeuvre backwards. Wait! The topography may be unfamiliar, but I recognise those wind-warped Scots pines. This must be the far side of Heron Island, and that means I’m nearly home. All I need to do is turn about and then, once clear of the jagged promontory, steer hard to port.

Close to shore now, I recognise the outline of the conjoined cottages and can even smell the damp wood smoke escaping the chimney. Finally hearing the crunch of the sand beneath the kayak’s hull, I exhale with relief and look up to a magnificent sky peppered with stars. I am delivered. Once I get home to Liverpool, I must try to capture and record this perilous voyage. I can’t do it in music, I know that. If it eluded Wagner, I am hardly likely to nail it in one of my three-chord wonders. I’m going to paint this experience, or at least attempt to. I’ve never worked in oil paint before, but that’s the medium I’ll choose.

Exhausted, I drag the kayak up the beach and upend it onto the grass with the paddle stored beneath it. Pulling off this ridiculous buoyancy aid and soaking cagoule, I tramp up to the door to the cottage, pull off my wet boots, and open the farmhouse door. Inside, it’s warm; wood burner roaring, the smell of dinner cooking, kids sprawled on sofas drawing. I haven’t even been missed. In the ninety minutes I now realise I’ve been gone, our friends the Walkers have arrived and are busy unpacking. Apparently, Nick has also brought a kayak up this year.

Mike passes me a bottle of beer.

‘Nice time?’ Jan asks.

Lost for words, I am a man transformed. Sheepishly, I don’t tell Jan or any of them about my experience on the loch until I am back on Merseyside a fortnight later, and even then I disguise the metaphysical stuff as ‘lost in fog’. People already think I’m mad.

*

Part memoir, part social history, ‘Revolutionary Spirit’ — the story of a cult Liverpool musician’s scenic route to fame and artistic validation — is out now and available here (£16.10).