In 2023, Christina Riley tethered herself to a swamp.

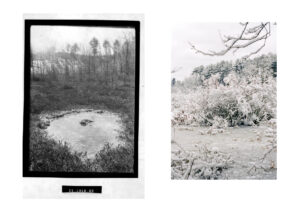

L: Photo by H.W. Gleason. Image courtesy of the William Munroe Special Collections, Concord Free Public Library

R: Photo by Christina Riley

All I know about Gowing’s Swamp is that Henry David Thoreau, at least once, wrote about it in his journals. That’s a difficult thing to unknow in Concord, Massachusetts, a town revered for its Transcendentalist roots: friends can meet at the corner of Thoreau and Walden, or take their children to Emerson playground. This is where I find myself at the beginning of January, visiting my sister and her family for an undetermined length of time, during which I’m reminded that I’m nothing if not a creature of habit. At the loss of my usual routines I tether myself to a place, using it as a metronome for otherwise uncertain days. In 2020 it was a beach. This year, it’s a swamp.

Despite wanting to remain uninfluenced by Thoreau’s lingering presence here, I soon search for the journal entry in which he summarises this quaking bog’s strange grandeur by suggesting that it offers as much wonder and discovery to Concord residents as the whole of Greenland might, and while it would be easy to suspect a hint of transcendental hyperbole, I know by now how dramatically one small place can unfurl the closer you look.

‘What’s the need of visiting far-off mountains and bogs, if a half-hour’s walk will carry me into such wildness and novelty?’

Thoreau’s Journals, August 30, 1858

In January the swamp is frozen solid, its water hardened to an opaque, milky ice, velvety soft beneath an overcast sky. The grey-white of the snow covered ground is separated from the grey-white clouds above by a vast entanglement of bare branches. Sticks protrude from the petrified ground, held in a state of suspense until the flesh of the earth can soften again. Somewhere in the deep peat, turtles are brumating, waiting out the winter.

As you enter Gowing’s Swamp through a narrow clearing you’re greeted by a young pine, its nimble branches still adorned with Christmas decorations made and hung by local school children. I don’t know it yet, but this tree will become a marker for my time here, morphing through the seasons’ celebrations. Pink hearts soon hang amongst the red and gold baubles, then glittery green shamrocks. By the time I leave, the limbs are laden with pastel, polka dot eggs.

A tornado tore through Concord several years ago, which explains why this previously spacious bog now looks like it got tangled up in someone’s pocket. Birds dart in and out of the thickets, shocking my tired eyes with their vigour. At first glance everything is a barren grey; only with prolonged attention do the colours and shapes begin to bleed through. Much of the vegetation is grey, yes, but it’s grey splattered with icy green and blue lichen, or it’s gnarled grey twigs twisting around the sharp scarlet stems of dogwood shrub. Colourless clumps are pierced with defiant flashes of red, and neon green pillows of sphagnum moss protrude through the bright white ice, like the remains of a forest fire coming back to life.

As though getting lost in the trees, sound here travels every which way. The splashing and spluttering of something in a vernal pool up ahead turns out to be a woodpecker, high up in a pine, behind me. All around, the trees are punctured with their hunger.

Near the centre of the swamp, one fallen tree is wide enough to lay down on, so I do. My spine rolls along the length of it like a chain, shoulder blades draping over the curve of the wood. Hands on my belly, my hips fall open so that my legs can hang off the sides until my toes rest on the soft ground. Chickadees flit between branches overhead and with my eyes closed, sunlight flickers through shaking pine needles. The sounds of the breeze and distant cars intermingle to add to the swamp’s soft hum. Storm torn trees lean this way and that, their broken limbs squeaking as they hold each other up. There is a constant feeling of something just about to collapse.

‘What means the maple sap flowing in pleasant day in midwinter, when you must wait so late in the spring for it, in warmer weather? It is a very encouraging sign of life now.’

Thoreau’s Journals, January 30, 1858

In the house, the days are driven by domesticities. Dinners are cooked, toddlers are wrangled into pyjamas, escaped family pets are retrieved, strollers are walked. My sister and I walk for so long, and so often, that we could draw a map of Concord off the top of our heads, putting pins in every place where the stroller-friendly pavement has been treacherously split by a tree bursting through the asphalt. I revel in being my nephews’ new favourite babysitter, and benefit from the fact that they’re too young to notice I’m making up the rules to Go Fish, which I have forgotten. I bring back leaves from the swamp to show them, and the five year-old tells me what kind they are.

Near the end of February it’s barely hitting 10 degrees, but on the sun trapped porch we unfurl a tartan picnic mat for the baby who sits straight-backed and rooted to the floor, like a plump little seed ready to sprout. He smooshes a teething toy onto his throbbing gums while one of his big brothers runs around us in circles, pretending to be a satellite.

The next morning, the view out of the window is nothing but white with an upchuck of freshly fallen snow.

‘That central meadow and pool in Gowing’s Swamp is its very navel, omphalos, where the umbilical cord was cut that bound it to creation’s womb. Methinks every swamp tends to have or suggests such an interior tender spot.’

Thoreau’s Journals, May 31, 1857

Thoreau is best known for his time at nearby Walden Pond, though in recent years, critics have been eager to denounce him for continuing to visit family for dinner, and particularly, obsessively, for bringing his laundry to be washed by them. Whether dedicating time to defend an undoubtedly flawed white man is worthwhile or not I don’t know, but something about this attack keeps tapping away at me. Thoreau is labelled a hypocrite, when what has possibly happened is that his reality isn’t living up to a projection that was thrust upon him by others; a romantic and reclusive ideal that never existed in the first place. I don’t think Thoreau ever stated an intention to remove himself from all civilised society, nor to receive help from nothing but his own two hands (it was his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson who wrote Self-Reliance). In Walden, the chapter ‘Visitors’ begins with Thoreau writing that he ‘love[s] society as much as most’ and is ‘naturally no hermit’. ‘I have three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society’, he continued.

Thoreau lived at Walden for just two of his forty-six years, the rest of them with his family to whom he was very close. His mother and sisters, Helen and Sophia, were active abolitionists, Helen the vice-president of Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society (which met at Henry’s cabin). The Thoreaus bonded over their shared political and familial values, forming a kind of alliance of people striving to make a beautiful world a just one. They helped each other in equal measures. They were a team, and to scrutinise the daily chores that one might have done for the other is to ignore the broader work that they toiled at together as a family. As Rebecca Solnit brilliantly puts it in The Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved, ‘the Thoreau women took in the filthy laundry of the whole nation, stained with slavery, and pressured Thoreau and Emerson to hang it out in public, as they obediently did.’

What Thoreau sought was to live ‘deliberately’, away from certain elements of society — such as consumerism, fashion trends and performative dinner parties — which contradicted his view of a good life. The friends who offered land to build his cabin on and assistance in building it, as well as those who visited him and walked the woods by his side, are well documented in Walden. He was curious to see how less might offer more, and how to shape a life which cultivated an alternative kind of abundance. This means of ‘simple’ living still allowed for the embracing of human connections that bring care and love; mutually supportive communities which have allowed us to get as far as we’ve gotten, so far, as a species. There is a lot we don’t need, but we do need each other, and that’s okay, is what I’m trying to say.

I am surprised to see that the earth there—under some snow, it is true—is frozen only about four inches. It may be owing to warm springs beneath.’

Thoreau’s Journals, February 1854

By March, the air begins to warm. The ground softens and squelches underfoot and curious croaks fill the air, heralding a more convincing coming of spring — a cacophony of frogs we can hear from the kitchen, though who I never catch a glimpse of even when I know they’re only feet away in the viscous vernal pools. The ice retreats into the belly of the bog and the meltwater at its edges awakens with tiny, writhing creatures; copepods, one of the most abundant animals on the planet.

By the turn of the seasons when the turtles, I imagine, are beginning to wriggle in their shells ready to come up for air, the thought of my returning to Scotland also starts to surface. I leave on the warmest day of the year so far. Not once, in three months, did I do my own laundry.

L: Photo by H.W. Gleason. Image courtesy of the William Munroe Special Collections, Concord Free Public Library

R: Photo by Christina Riley

*

Visit Christina’s website here. You can also follow her on Twitter and Instagram.