This year, Pamela Petro acquired a treasured Welsh tapestry coat.

Planning a book tour is like turning yourself into a chess piece and asking competing players to move you across the board.

Maybe Waterstones in Liverpool offers you a slot on Monday. Hooray! But then you can’t schedule Waterstones in Swansea for Tuesday, as they wish, or you’ll be crosshatching Wales with your carbon footprint. But what if the great indie, Book-ish, in Crickhowell, says they can only have you on Tuesday? Well, off you go, hoping Swansea is free another day and that your friend’s car gets good mileage. (They do, it does, phew.)

A lot of emails flew back and forth across the Atlantic as I planned my tour. (I live in Massachusetts.) You’d have thought I was plotting troop movements. I say this not to moan—it was a privilege to read to audiences from my new memoir about Wales — but so you’ll appreciate my secret lodestar, the one constant I refused to alter as I skuttled a herky-jerky path across the chessboard: no matter what, I had to find a legitimate reason to be in Abergavenny on a Tuesday, Friday, or Saturday.

I didn’t need to get there because Abergavenny has the biggest bookshop or because townspeople were clamoring to hear my book. I had to be there because Tuesdays, Fridays and Saturdays are market days in Abergavenny, and I had come to Wales from America to go to the Abergavenny market.

OK, sure, I was really there to promote the book. But the carrot in front of my nose, drawing me forward through the snow — boy, did it snow this past March in Wales! — was Bellemoon Vintage & Welsh Blankets, a shop I’d been following on social media that only materializes on Tuesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at the Abergavenny Market.

I have a few, treasured Welsh blankets. I teach a creative writing school in Lampeter each summer, and one of the highlights is taking students to Jen Jones’ Welsh Quilts and Blankets — a fantastical shop in a tiny, 18th century cottage in Llanybydder — where the Welsh blankets call to me like wooly sirens.

But Bellmoon was posting images of vintage 1960s Welsh tapestry coats, and I longed for one of those. What could be better than wearing a blanket? It briefly occurred to me I might look like a bed, but ultimately…so what?

When I snagged a gig for a Saturday at the smallish Waterstones in Abergavenny, I rejoiced! My secret plan was in place. And so, on the final Saturday of my book tour I made my way via car, train, and long footpath to the center of Abergavenny and asked for directions to the market.

Textiles are as much a product of the Welsh countryside as Caerphilly cheese and leeks — you just can’t eat them. They emerged from an alliance between sheep, fast-moving rivers, cold winters, and human ingenuity. Around 1900 there were over 300 water-powered woolen mills in Wales. Today there is only one dependent on water — Rock Mills in Capel Dewi, corkscrewed like a secret, hard-working fairy tale into the Towy Valley — though there are around 10 mills still in production.

Welsh textile mills disappeared one by one throughout the 20th century, though there was a resurgence in the 1950s and ‘60s when Welsh tapestry designs roared back into popularity. Welsh “tapestry” is actually two layers of different colored cloth woven together to create geometric patterns with traditional names like “hiraeth” (an unrequitable longing—it’s what my book is all about), “portcullis,” also known as “Caernarfon,” and “St David’s Cross.” The layering makes for mirror-image, double-sided designs in reverse colors.

In writing, as in life, you have to make decisions: go in this direction or that. Choose this metaphor or another. But Welsh tapestry gives you two options. It knows that we can’t always choose — that life, too, is often double-sided.

After all the hoopla of getting to the market, closing in on Bellemoon seemed almost too easy. Once inside, I got cold feet. I fretted that the coats would be too expensive or wouldn’t fit — or, God forbid, they wouldn’t have any. I slowed time by poring over bric-a-brac, but my eyes disobeyed, scanning the riot of stuff until they honed in on a bit of Welsh tapestry emerging from behind a display case. And there it was, the shop, in the far corner.

I gave up all pretense and raced between tables and racks to reach it. At Bellemoon I found Welsh tapestry pillows and handbags, change purses and make-up cases, capes and…coats. A whole rack of ‘em. With shaking fingers I slid each of the hangers toward me, one by one. The colors were a little too 70’s mod — daffodil-yellow and neon orange — or too prim: beige and oatmeal. I felt disappointment congealing in my chest, threatening crankiness. But Bellemoon’s owner bounded over and ordered me to have a second look. Before long a crowd of women had gathered.

“Ooo, I think maybe she’s going to buy a coat,” said one of them.

“Don’t you just love it when someone buys something expensive?” her friend murmured.

On the second hunt, halfway through the rack, I found it: a weave of cranberry, lavender, and what I’ll call electric-raspberry, to avoid saying “hot pink.” A double-breasted, three-quarter length woolen coat from the mid 1960’s. I slid it on, and my eyes met the owners’ — there was no denying it. The coat was a perfect fit.

“It was owned by a woman who lived here in Abergavenny,” she said. “It seems she hardly wore it.”

Perversely, I tried to argue against it. I protested that the sleeves were too short. The owner explained that in the 1960’s, the Welsh middle class, finally having a bit of money, wanted to show they could afford long leather gloves—so they shortened arms of their coats. Another shopper tried one with sleeves that would’ve fit a T-Rex, and left without a purchase. But mine were just a bit above the wrist.

The owner took photos from all angles. I made three trips to the full-length mirror. The assembled women waited and cajoled, some drifting off in exasperation. Finally, giving in to what I’d decided in my heart half an hour earlier, I took off my down jacket, stuffed it in my backpack, paid the owner, and left her stall in The Welsh Coat.

“Oh, you got the COAT!” a woman cried as I entered a nearby shop, half an hour later. “Look!” she called to her daughter. “The American woman bought the coat!” The daughter came running and we all congratulated each other on its existence, as if we three alone had kindled a 50-year-old dream back to life.

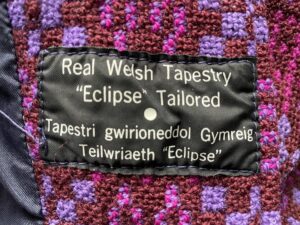

I now wear The Welsh Coat everywhere, and to my never-ending glee, someone usually admires it. These are the tags inside:

I’ve had a crazy-hard time finding out what ‘“Eclipse” Tailored’ means. A friend came up with an Eclipse Woollen Mill in Lexington, Kentucky. Nope, not that. I found an Eclipse coat designed for electric, gas, pipeline construction, and petrochemical workers in a liquid-proof, flame-resistant PVC material. (All that, and lightweight, too!) Not that either.

My partner finally found an image of a beautiful logo, reminding wearers of the waterpower of the Welsh countryside — and along with it, of the rain, the hills and valleys, the luminescent greens of grassy pastures, the sheep that eat the grass.

My coat doesn’t bear the logo. Just as the company seems to have experienced a total eclipse of its art (sorry; couldn’t help myself), the logo was eclipsed somewhere along the line. Some of those valleys have been eclipsed, too — it’s always just six degrees of separation in Wales from the 1965 flooding of the Tryweryn Valley to provide water for Liverpool. That experience is woven into the coat as well. In fact, maybe the original owner was buying the coat in Abergavenny just as the taps turned on, 120 miles north, and the valley began to disappear under water. There are all different kinds of water power at work in Wales.

All of this is in the coat: the sun and rain and photosynthesis, the rivers, the loss, the anger, the artistry, the pride of a rising middle class, the hiraeth of an American from Massachusetts who found her passion in Wales, the camaraderie of women in a bustling Saturday market. The lining prevents me from seeing the reverse pattern of the weave on the inside, but I know it’s there. It speaks for what is and what could have been. What we see now and what we remember. What we have and what we long for. How appropriate that one of the Tapestry patterns is called “hiraeth,” that untranslatable Welsh word meaning a yearning for the impossible. The once and future dream.

Hiraeth may refer to an intangible, but sometimes, for £125, you can buy a pretty fine stand-in for it.

*

Pamela Petro is the author of ‘The Long Field: Wales and the Presence of Absence, A Memoir‘, which was shortlisted for the Wales Book of the Year in 2021. She co-directs the Dylan Thomas Summer School in Creative Writing at the University of Wales Trinity St David.