In a time of pictures and films on a million phones, an unlabelled 7″ reminds Jeb Loy Nichols of the possibility of being uncatalogued.

Bernard Drake

I’ve Been Untrue

La Louisianne

1969

At the edge of the lake I spend an hour doing those things I often do; I sit on a rock with a book, periodically reading a paragraph, watching the sky and frost bitten shrubs. Streaks of blue sky mingle with the grey. The book I’m reading is a battered copy of The Tao Of Nature by Chuang Tzu. There is, on the cover, a circular stain left by a tea cup. Sticking out from the pages are several book marks. I open the book at random, scanning the familiar pages.

Are people too cheerful? Are people too vengeful? People are unable to maintain a balance between joy and anger. It makes them restless, moving here, moving there, plotting to no purpose, travelling for no reason or result. The consequence of this is that the world becomes concerned with mighty goals and plots, ambition and hatred.

A sharp wind, full of winter, gusts between trees. The day is promising but not definite, as if it could, at any minute, become something new.

On the walk home an owl squeaks; the moon, moved west, is obscured behind sycamores. A fox’s musk, a rough wind, the remnants of a warning yelp. There’s an entire layer of noise and meaning to which I have little access, my ears and nose and eyes being dull tools. As I walk the silence thickens; I think about how, as a teenager, I went to a movie for the first time and was terrified by the violence of the soundtrack, the relentlessness of it. I would have preferred silent films. I like the idea that silent films weren’t silent so much as the audience was made deaf. The actors carry on as usual but can’t be heard; the audience is plunged into a blissful quietude. The introduction of sound was just one more step into audio panic, into technological domination, everything given a voice; the world became a willing victim in a tyranny of noise.

These days I listen to less and less music. I prefer the wind, the rain, birdsong. Occasionally I’ll put something on; 45 rpm records are tailor made for me. Someone telling a story that must, given the size restrictions of a 45, be over and done in three minutes. Perfect. I put one on, listen to it, and feel like someone has come into my life, told me a story and can now leave me in peace. When I got home from the lake I played the disk that was on top of the pile; ‘I’ve Been Untrue’ by Bernard Drake.

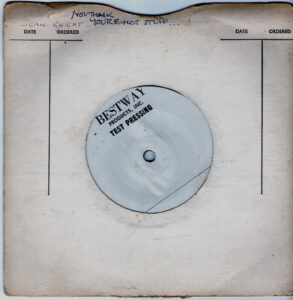

When I bought this record I didn’t know who it was. I didn’t know for nearly thirty years. I bought it in a flea market in Tennessee. I remember picking up a stack of test pressings, none of which had labels, and handing over 5 dollars. One of them turned out to be ‘Stoney’ by Dan Penn. The others, with the exception of the Bernard Drake record, were obscure country western tracks. When I played the Bernard Drake record I had no idea who it was, only that it was brilliant. I asked a handful of people about it but no one could identify it. I was pleased – I liked not knowing who it was.

Forgetfulness, or a kind of not-knowingness, is the only way we can live in the world. What’s the good of all this remembering? A man who forgets nothing is condemned to be constantly at the mercy of that remembrance. Does a squirrel remember everything? Does an oak tree? If we constantly gorge ourselves on memories and never get rid of any of it, won’t we all become obese? Should we not turn our backs on remembrance, or at least on those aspects which are least personal, most general? Forgetting, rather than remembering, should be celebrated.

We should ask ourselves each night, what have you forgotten today?

That was one reason I loved my unidentified test pressing. It stood firmly against the horrific over documentedness of today, all the pictures and films on a million phones, the entries on a million websites; it reminded me of the possibility of oblivion, the possibility of being uncatalogued.

In 2020 the label Hit And Run reissued a track by Bernard Drake that had originally come out on La Louisianne in 1969. My mystery record was a mystery no more. Of course I’m pleased that Hit And Run have made a brilliant record available once again. It sounds better that ever. Pure genius. I bought a new, clean copy. I play it when I get the need for a three minute story. But I still have no idea who Bernard Drake is. And please, if you know, don’t tell me.

*

You can follow the Jeb’s Jukebox Spotify playlist here.