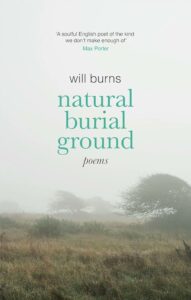

March Book of the Month was Will Burns’s ‘Natural Burial Ground’, published by Corsair. In amongst the invasive flora and upset ecosystems, Emily Hasler finds affection for the imperfect and the impermanent.

There’s a directness to Will Burns’s work which is disarming.

Late winter crows and water-crowfoot,

slant-lit, shallow. Gin-clear.

Cress farm memories under cut glass.(‘Chalk Elegy’)

A few short sentences. Clipped, weightless clauses. But what may seem idyllic and transparent is deceiving: ‘Still looks like a chalk stream on the surface, sure.’ So it is with Burns’s poems themselves: the immediate lucidity lures us into less certain depths. His second full collection, Natural Burial Ground, takes us beyond the surface and shows how our landscapes are shaped by loss, layered with grief.

The collection moves between a handful of locations, including Jersey, the Scilly Isles and the Home Counties. The relationship with place is one of familiarity and we’re welcomed without ceremony or introduction, as if entering a public house. In ‘Off Island’ Scilly is presented in precise, pungent language:

Scilly stonecrop, the problem pittosporum,

verges full of onion funk, gorse and wire plant.

These are no shiny tourist brochure images: here is smell and texture; invasive flora and upset ecosystems; dying industries; living in spite of the difficulty in making one. The ‘Strata of habitation – a taxonomy of foliage / and standing stones, bronze and Bakelite’ speaks to the provisional nature of island life, of making do. In these sea-restricted spaces there is nowhere to hide the ‘Signs of life and what’s come next’ (‘Occupation Site’).

As on an island, we cannot ignore or escape mortality in Natural Burial Ground. As well as tributes to the late singer-songwriters Mark Lanegan and Tom T. Hall, there are personal bereavements. In ‘A Red Path Through the Wood’ we’re privy to ‘your hand smoothing, finally, your mother’s blonde hair.’ It’s a typically intimate and acute detail. The collection opens in Jersey with ‘Corbière Farm’:

That summer the eldest of the old dogs died

and the house suddenly felt like the wrong place.

The ‘old dogs’ hint at a long association with this place, just as the death signals an unsettling change. The farm takes its name from the treacherous, rocky stretch of the south-west coast of the island and means ‘gathering of the crows’. Portents crowd the poem, suggesting an upset to the usual order:

the cockerel across the river

began to sound off at strange times –

late into the morning, throughout the afternoon. Midnight.

These might be omens of death, foretelling the fate of an individual, a family, or even the farm. Or perhaps this is not a symbol but a sign, indicating the collapse of nature itself?

The breakdown of our environment is another source of grief in these poems. In ‘Dabchick’ Burns perfectly animates the little grebe, no sooner seen than disappearing: ‘Little frog-like shape / half-swimming, half flying underwater.’ Though there is still pleasure in walking, fishing, being in nature, much has gone – lost within the poet’s lifetime:

I could find that grassland,

the rough blades still grazed back,

but the butterflies would be gone.

This last summer was just too cold

‘Natural Burial Ground’ refers to one of the few growing industries in isolated rural communities – that of woodland or ‘green’ interment sites. You can imagine the locals joking darkly about it in the pub: this place which offers little in the way of future or opportunity, which is ‘Dying on its arse’. The title poem is set in Wendover, in Buckinghamshire where Burns lives:

Functional drift of obsolescence,

lease run down, estate to make good,

the militaristic blended into the petrol station

and the Chinese next to the vet’s.

The other part of the ‘joke’ is that while building HS2 a mass grave is discovered. Here is already a burial ground. Here’s somewhere that was once important, now just a place to be destroyed en route to elsewhere.

Meanwhile, our bodies let us down, our youth is lost, memories fail. But there is beer and song, and, though it is built upon a geography of grief, there is nothing sombre about Natural Burial Ground. Instead – since grief goes with us everywhere and is everywhere we go – there is affection for the imperfect and the impermanent, wry humour, and joy – most vividly in music and encounters with the natural world. One such moment, which fuses the two loves that emanate from this tender, generous collection, comes in ‘Dolphins’. Neither the mythos of the animals – ‘The Greeks had them down as telegram boys of the gods’ – nor description of them can convey the sensation of the encounter. Instead

… it’s Fred Neil’s deep blues for me.

For you the best bit of Beth Orton’s ‘Best Bit’ –

that sultry slack that gets into your bones

each summer. Languor, looseness.

In moments such as this, Burns gets it just right.

*

‘Natural Burial Ground’ is out now. Buy a copy here (£10.44).

Read ‘Smoke Rise and Sam’s Place’, and ‘Dolphins’, extracted from the collection, here and here.

Emily Hasler lives on the Suffolk-Essex border beside the River Stour. She has ME. She writes (when she has energy, which isn’t often) and swims all year round (except when she’s ill, which is much of the year). A few years ago she decided she should get to know wildflowers. Her latest collection of poems is ‘Local Interest’ (Pavilion Poetry, 2023).