As Jennifer Lucy Allan’s ‘Clay: A Human History’ is published by White Rabbit Books, Luke Turner considers the martial landscape: the ultimate human collaboration with topography and geological time.

Soldiers of an Australian 4th Division field artillery brigade on a duckboard track passing through Chateau Wood, near Hooge in the Ypres salient, 29 October 1917. Australian War Memorial collection number E01220. Photographer: Frank Hurley. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

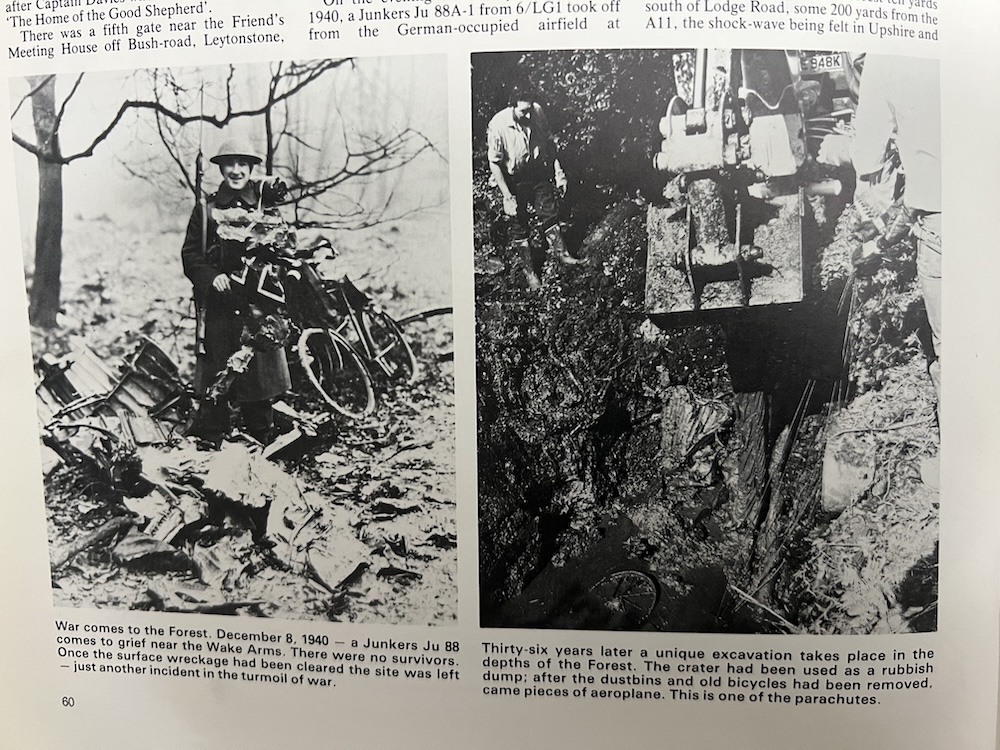

The arm of the digger reaches down beneath the surface, clawing at wreckage. Someone peers over the crater, marvelling as the teeth of the bucket bring up twisted and broken metal amidst gushing water, oil and dirt and then, something fabric, stained, but no mistaking what it is: a parachute, one that was used but never opened, instead preserved in the thick clay of London.

This was an image in a book called Epping Forest Then and Now. It obsessed me as a kid, seeing time move in black and white and a changing landscape, and I’d say it was one of the formative inspirations that led me to want to end up memorialising both men and place in words.

Amidst the photographs of suburbia encroaching on Essex countryside were these images of the exhumation of aircraft wrecks from the Second World War, Spitfires, Messerschmitts, Junkers bombers that fell from the sky at such high speed they performed their own burials.

Human progress is marked by our exploitation of the elements in order to create new weapons – this gives us the delineation of time into stone, bronze, and iron age. This centres the human ingenuity and inventiveness in destroying the human body but, it seems to me, overlooks how all the elements of the natural world become part of our experience of conflict.

Geology has always shaped warfare, and warfare geology.

The martial landscape is the ultimate human collaboration with topography and geological time. Where agriculture or town planning finds obstacles to be overcome, the military engineer sees opportunity in what is already there. Men are protected by rock, aggregate, concrete, soil and clay from metal and high explosive.

How best to kill or defend alike comes from the human imagination and understanding of the material beneath our feet. Geology overrides all. Areas heavy with clay are often flat, historically the ideal terrain over which armies of conquest can quickly march. I was struck recently by election maps from the UK and France. Four of five of Reform’s seats are in the flatlands of Eastern England, and National Rally did well in the expanses of Northern France over which the First World War was fought. Geology influences a fear of the other.

The soil underlying much of the Western Front between 1914 and 1918 was heavy with clay. Poorly-draining, this made for the horrific wet conditions for which the trenches became infamous, in which so many millions of men suffered, and into which so many of them vanished.

Clay was an easy material to tunnel into, and both sides dug through it to undermine fortifications with huge explosive mines, or to find the enemy tunnels being built for that purpose. When the two met, the combat in these enclosed spaces was vicious, brutal, hand-to-hand, blood and breath, fear and hate as elemental as the clay around them.

This in turn makes me think of even more elemental, even cosmic legacies of our modern wars – a recent study has found evidence that the power of the million bombs dropped on occupied Europe between 1939 and 1945 could even have altered the structure of the ionosphere, 1000 km above the earth.

Between ionosphere and oomska millions of men fought and died. I think of them as elemental as our atmosphere, as clay, as the atoms of metal in machines with which they thought.

From ‘Epping Forest Then and Now’

In my book Men At War, I wrote of the desire that flowed through their rough, beautiful bodies. Thanks to the myth-making of national histories and culture, we forget their lives were unimaginably diverse, sensual and erotic too, in favour of ruin fetishism and the glorification of death machines.

These are all things I have tried to unlearn. These are all things our culture should unlearn.

Think of their bodies. Skin against steel. Flesh within concrete. Flesh disappearing into earth.

We’re currently moving beyond the living memory of the Second World War. It exists now in documents to be argued over, but also in the elemental remains and imprint on our earth. I often imagine the metal of war machines melted down and recycled, the aluminium of German aircraft that didn’t ended up buried in London clay melted down to become new, British aircraft, and then after the war scrapped to become homes, domestic items, packaging, their molecules around us still today in cars, cans of beer. It’s as if we’re surrounded by the ghosts of machines in which men experienced such horrors, and from which they visited such horrors on men, women and children.

The defensive and military structures built onto our earth gradually sink back into it. That dialogue between what we call nature and what we think of as the unnatural materiel of violence is in itself a fecund energy, of slithering, creeping, enveloping. As plants overgrow these objects of war, and weather corrupts them, and fauna colonises them, they become accidental memorials in which we might reflect on the taboo, shame, silence, absence of the body, the rough complexity that resists exploitation for jingoistic ends.

I think of those tunnelers through the clay battlefields of the First World War, and those thousands of men whose bodies were never found. Skeletons still lie twisted together entombed, so different from the clean white stone of the cemeteries that cover a region now at peace. A more sinister memorial and legacy is now being discovered in the form of research that shows the clays of the Flanders landscape have had their chemical composition transformed by the heavy metals left behind by millions of exploding artillery shells.

In brutal Soviet Second World War film Come and See, the skull of a German soldier is covered with clay to make a grotesque mannequin of Hitler, carried on a pointless raid to try and get supplies for the partisan group. It’s an effigy full of the horror of war, a horror that those polite white stone, or grandiose bronze of more martial monuments, are designed to ignore. The final shot of the film is of child partisan Flyora, his face dirty with the Belorussian soil, corrupted by the horrors he has witnessed, the warning of what happens to youth whose masculinity is seduced by ideologies of violence.

Flyora in ‘Come and See’

With our eyes we can break down the physical manifestation of these back into the earth itself by thinking of how these metals, concretes and soils were for a while the working, living, fighting places for so many men whose forms were enclosed in the uniforms of their countries, and sent so far away from home to fight.

Those pictures of aircraft wrecks move me in a different way now, far from the excitable kid revelling in destruction. Instead, I think of concrete and steel, soil and clay not just as the hard matter of war but, as they are touched and caressed by water and leaf and wind and vine, as symbols of bodies now broken, but once loved and touched by lust.

*

This article was originally written as a talk given in response to Jennifer Lucy Allan’s ‘Clay – A Human History’, published by White Rabbit Books. Read Annie Lord’s review here.

Luke Turner’s ‘Men At War’ is out now in paperback (£10.44).