Ian Preece pays tribute to John Broad, a.k.a. Johnny Green — author, Rouleur columnist, and road manager for The Clash, Joe Ely and John Cooper Clarke — who died in March aged 75.

In the film Rude Boy, and in other online footage of The Clash as they pile onstage at Rock Against Racism in Victoria Park, April 1978, there’s a five-second glimpse of road manager Johnny Green and his two young daughters, Acorn and Goldy. In his book A Riot of our Own: Night and Day with The Clash John wrote, ‘I felt quite proud that my kids had come to see Daddy at work. A guy in a silk tour jacket – a Tom Robinson roadie – said, “Who let these kids up here?” I said, “I did. So what? Fuck off.”’

Twenty-eight years later, in the summer of 2006, it was late, gone midnight – the first night of the first Latitude festival. We’d just retired to our tents. All four of us (our kids were only 7) were in our crappy tent, surrounded by a laager of Broads (John, Janette and their young brood: Ruby, Polly, Earl) in theirs, when some other campers returned, one of them brandishing an acoustic guitar and loudly proclaiming: ‘Let’s get this fire going!’ I heard John sigh in the neighbouring tent, the rip of a zip being undone. I winced in anticipation. There were many advantages to hanging out with the ex-road manager of The Clash, and a decent night’s sleep in a field was just one. There was no clambake.

At the same festival John checked out the stand-up poetry tent to reacquaint himself with an old compadre from the punk days: before long he’d become John Cooper Clarke’s ‘gentleman travelling companion’, reprising his Clash role of cutting through the bullshit and time-wasters and ensuring smooth passage to the green rooms of Leicester De Montford Hall, the Flowerpot in Derby, Baths Hall, Scunthorpe, etc; hours spent speeding up A-roads discussing the Talking Pictures schedule, literature and the nature of comedy. (Too ill to drive JCC around anymore, but still integral to the whole operation, plans were drawn up for John to direct affairs from his own quarters on the spring 2025 Cooper Clarke tour bus – the prospect of becoming the first road manager ever to be assigned a road manager delighted him.) At the same Latitude festival back in 2006 John also hooked up again with Patti Smith, who he had a lot of time for; later ferrying her and other authors like Willy Vlautin and poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy from isolated rural train stations to Richard Thomas’s literary tents at the Laugharne, Latitude and Green Man festivals.

But John wasn’t just a road man: as often as not he’d be up on stage himself, sparring with and interviewing authors promoting their books – Don Letts, Jah Wobble, Paul Torday, John Cooper Clarke himself – sometimes reading from his own work: frequently A Riot of our Own (written with Garry Barker), his inside-track on days with the band, often billed as the definitive book on The Clash, a title which hasn’t been out of print since 1997.

Before punk Johnny Green lived other lives. He was born John Broad in a maternity home in Chatham, Kent, in July 1949. His early years were spent on the Twydall estate in Gillingham, where his parents, Jack and Margery, were primary school teachers. Jack was renowned for his NUT work and later became the first head of a school in Kent to ban corporal punishment. He also bought a plot of land and built a bungalow a stone’s throw from Gillingham FC’s Priestfield ground – John’s football addiction kicked in young. Observing the comings and goings at the end of his road, fastidiously collecting the autographs of the likes of Gillingham defenders (‘psychopathic-looking’ Roy Proverbs and Mike Burgess with his ‘cantilever haircut’), John sniffed out early a peculiar mix of the quotidian and 1950/60s glamour (albeit via the English Third Division. On another autograph-hunting occasion, the football-mad youngster managed to squeeze onto the Man Utd first-team coach taking the stars of Matt Busby’s second great side from their hotel in Russell Square to a game at Stamford Bridge. Bobby Charlton tried to throw John off the bus – but Denis Law intervened; a case of one maverick looking out for another, early doors, as it were.)

On leaving Gillingham Grammar School John sold copies of Gandalf’s Garden and International Times magazine around the Medway towns (sourced from the ‘head shop’ at the World’s End, Chelsea) and struck up regular correspondence with John Peel through the latter’s Perfumed Garden show. John moved north to York University, where he lived in a ‘meditative commune’, dropped out of his philosophy, politics and economics course, but married his girlfriend Richenda. The pair then moved further north, to Scotland, John working for the Forestry Commission in Kinloch Rannoch (a deep love of the glens and mountain walking, and strong opinions on porridge-making were forged) before settling back in Yorkshire in a cottage in Moor Monkton with their two young daughters, Acorn and Goldy, and following the hippy trail into the nascent wholefood trade – working in a collective, milling flour, then overseeing a number of ‘grain’ enterprises in Snowdonia and Hull. (This slays me now: I knew there’d been a bit of dipping into tubs of dried cranberries and raisins – but all this from the man who remained unremittingly dismissive of my early enthusiasm for Midlake, Espers and fellow felt-booted, freak-folk, Brattleboro-based troubadours like Feathers.) In 1974, still up to his neck in flax, but influenced by a lecturer at Hull University, Andrew Rawlinson, John enrolled for Arabic and Islamic Studies at Lancaster University – while there he ran a student disco with his pal, fellow undergraduate ‘Stevie’ McCarthy (today éminence grise of Deptford Dub Club); Richard Hell and the Voidoids and Augustus Pablo came to replace the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band in his affections; and he established a not-for-profit wholefood store called Feedback. By the autumn of 1977, freshly graduated but also newly divorced, he was ready to return to Tunisia following a student placement in North Africa and keen to explore Yemen, that ancient crossroads of civilisation, in depth – but at a joint birthday party for Acorn and Goldy he ran into an old friend from Gandalf’s head shop, John Hallaway, now organising transport for this new band called The Clash; the next morning, via the Stranraer ferry, the pair met Joe Strummer in Belfast; John’s first gig followed in Dublin…Wielding gaffer tape, speeding up motorways, spearing fools, sidelining fakes and geeing up the band ‘like a football manager giving a team talk’, John took to the berserk energy of punk like a crazed duck in Praia do Norte, Nazaré: ‘I loved the sheer magnitude of the panic attack that took hold as the time for the set approached. Junkies talk about the rush of smack being like six white stallions galloping up the spine to the brain. This was better. This was pressure, building and building from the inside, but just knowing it was worth doing made me learn to ride it out, until surfing on the lip of the tidal wave of anxiety became a buzz in itself.’

But, for John, while the initial explosion of punk was a moment of simple purity, punk was…exactly that: to be experienced in the moment – he wasn’t interested in legacy (even though for the rest of his life waifs and strays he’d let into Clash gigs for free continued to stop him the street to express love and gratitude), and he certainly wasn’t interested in any safe, predictable corporate rock machine. After working the early 1980 Clash tour of the States, and receiving a condescending thumbs-up from the impresarios’ impresario Bill Graham in New York, he turned his back on it all. He wanted to live in America, to ‘touch it’, not see it through the windscreen or the hotel bar window. He was impressed by Lee Dorsey, he left The Clash, was drafted in to sharpen up their Texas country soul brother Joe Ely’s touring operation – by which point he’d met and married exuberant punk scenester/designer Lindy Poltock – moved to Lubbock, but ended up jumping bail after a difference of opinion with a cop in Austin over what constituted ‘dangerous’ driving had gotten out of hand.

Back in London John worked for Stiff Records then Fifth Column t-shirts; Lindy gave birth first to Earl then to Dirk, but died suddenly of pneumococcal meningitis – Dirk, too, a fortnight later – in Whipps Cross hospital in 1983. Rudderless for a while, John ended up back in Kent. As Earl puts it today, ‘When the chips were down, he realised a more stable environment was required in order to bring me up and he entered a profession he’d always vowed to steer clear of…’ At teacher training college in Canterbury in 1985 John met Janette Border, who became his soulmate, future wife and grounding force for the rest of his life. Janette graduated to become a maths teacher; for John, it was a case of not only ageing Clash fans stopping him in the street, but a whole generation of schoolkids from the North Kent Coast, eager to recall times spent with their old R.E. and sex education teacher (like his dad, he even became father of the NUT chapel). Aubrey Harris, a colleague and close friend, remembers the new R.E. teacher arriving at Faversham’s Abbey School: “On his job application John had passed off his Clash years as ‘organising social events for young people’…John’s teaching style proved to be interactive to say the least: most of his lessons turned into mini-riots, with him at the centre, orchestrating things. He had great empathy with the kids.”

For John and Janette, Ashford in the eighties became Whitstable in the nineties; and Earl soon had two younger sisters to hang out with, Polly and Ruby. As Aubrey noted, John always got on with the kids: he was quietly super-proud of all his own; and our two were straight into the back of the car for a trip to see ‘the Broadies’. It was also a total pleasure to edit John’s books (and you can’t say that about every writer). It’s those early 21st century days that I recall most fondly: sunny afternoons in Whitstable when it was still, if not quite a grimy fishing port then at least not the DFL mecca it’s become today; or hanging out at festivals, John easing into his new life as a writer semi-camped in the cycling and music worlds, brandishing his stove-top coffee maker in the mornings, holding forth on various authors/cyclists/bands/footballers/religions; putting a world of chancers and squarejohns to rights; kids running free everywhere. Back home he’d ruminate on the changing tides of the Thames estuary; the cassette player in his living room would be playing Guy Clarke’s ‘Like a Coat from the Cold’.

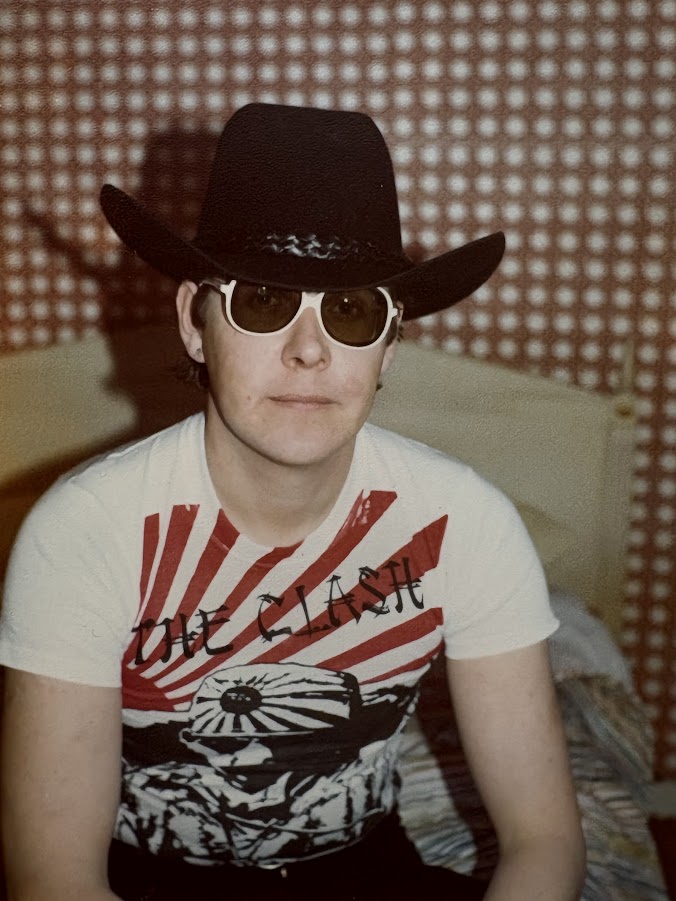

John was a brilliant author and raconteur: thoughtful and astute, with hilarious alacrity, everything – be it Rimbaud (a pencil drawing of ‘the original punk’ sits above the fireplace in Whitstable); the country laments of George Jones; Bob Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour; Eddy Merckx’s perfect hair; Marco Cippolini’s 400 suits; Hank Williams’ stage craft; the life and times of Gillingham centre-half Barry Ashby (one story involved the Medway legend, the open boot of a car and a baseball bat); Michael Herr’s Vietnam Dispatches; life in Yemen; or a train ride through the Canadian Rockies – would be processed through the Green/Broad filter to emerge in needle-sharp prose on the page or on the stage or just in everyday conversation. Following A Riot…John took the same gonzo modus operandi to another world he loved, cycling, for Push Yourself Just a Little Bit More: Backstage at the Tour de France (2005), one foot in the press box for access, the other, crucially, on the outside, riffing constantly with Earl under the burning sun of the Massif Central or on the slopes of Mont Ventoux. (He’s explaining what lies behind the monument to Tommy Simpson to a young Polly and Ruby in one photo here.) Earl was also a fixture by his side at the Priestfield as they navigated the twists and turns of chairman ‘Mr Scally’s years. They both complained I cut out too many food references from Push Yourself… They were considerably ahead of the seemingly inescapable hot-new-gravy/pie/taco/locally-roasted/alfresco-pop-up-streetfood-shack 21st century wave of food fetishism/marketing spiel – but given that, long term, I’m still confident I was right.

I first met John with publisher Mike Petty (who commissioned Riot) in a pub on the Strand in 1996 – at the time John was seeing therapist Bill Reading; his rock’n’roll years in the rearview mirror, his young family and nascent writing career in the front seat, he steadfastly drank Coke all night. John never did anything by halves. We never had a phone call without discussing books. The last time I spoke to him he was absorbing some Japanese death haikus because he “always like[d] to be ahead of the game”. There’s no question the world is a lesser place without the planned Johnny Green volumes on Beatles road manager Mal Evans (a kind of lodestar for John), his opus based around years of correspondence with another blood brother from the punk days, the artist Ray Lowry (they shared roots in Cadishead, Salford, where John’s dad was from), and his Joe Ely-in-Texas reflections and recollections. There was a time when he nearly midwifed Topper Headon’s autobiography into the world. Then there was the hugely anticipated: Row Yourself Just a Little Bit More: Backstage at the Henley Regatta. He was also toying with fiction. Chapeau, mon ami – in your mad intensity, beautiful generosity of spirit and total respect for the unserious side of life, you showed everyone how to live. John is survived by his lovely family: Janette, Ruby, Polly, Earl, Goldy, Acorn and four grandchildren.

(With thanks to Janette Broad, Earl Broad, Polly Broad, Ruby Broad and Aubrey Harris; truncated, heavily edited fragments of this appreciation first appeared in the Guardian, ‘Other Lives’, 17th April 2025.)

Johnny Green/John Broad, 30th July 1949 – 2nd March 2025