Brenton Wood teaches Jeb Loy Nichols about the flux of life.

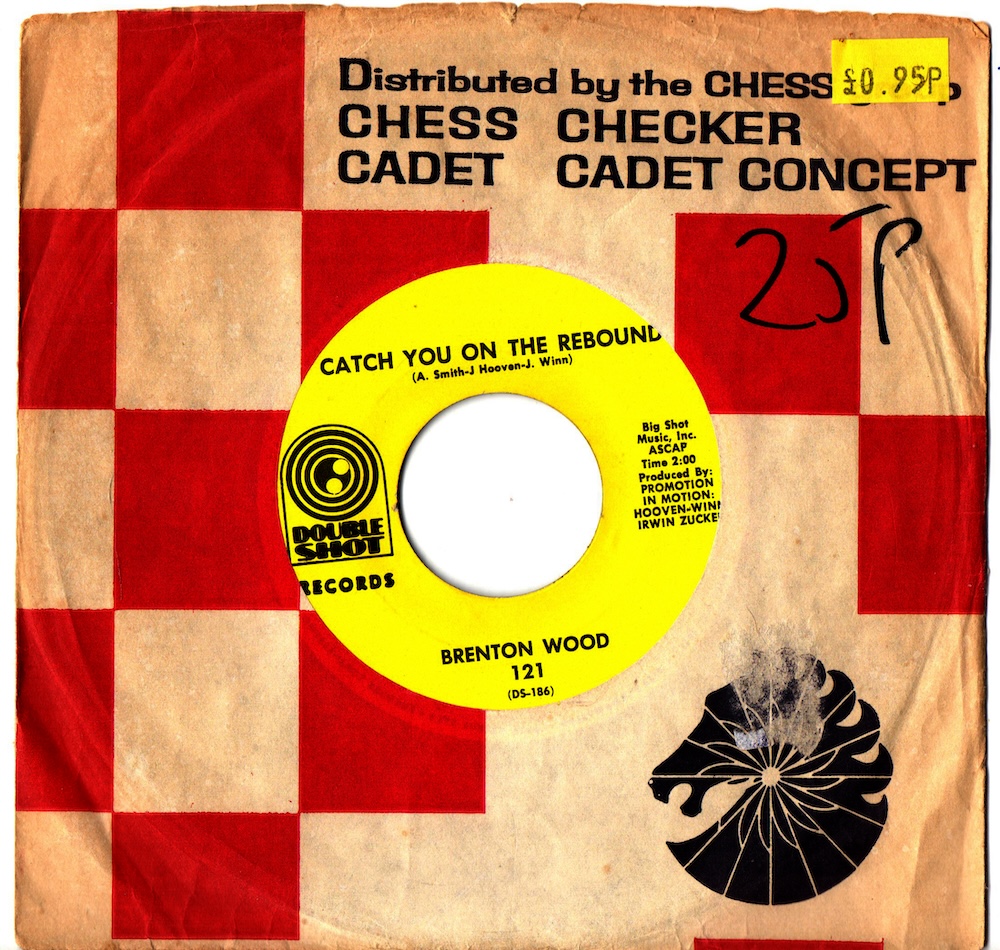

Brenton Wood

Catch You On The Rebound

Double Shot Records

1967

When I first came to London, nearly 40 years ago, I lived for a while in Kilburn where all the old men smoked their spliffs and drank their liquor and told confusing stories about women. They also gave detailed breakdowns about which neighbourhoods were likely to have rooms to let and at what prices. Also where you might get work. They wore cheap shoes and hats. They told lies. They complained. They postured. They talked endlessly about lack of money and lack of respect. They wore clothes from cut rate shops, they were lazy and they worked hard and they were funny; they had wives and girlfriends, often at the same time; they treated children and dogs with a grave approval.

I contrived, when I first arrived, to be often alone, walking home at night, nodding at street cleaners and taxi drivers. I felt both very old and very young. I wondered about something I’d read, a thing called sadness-for-no-reason. I wondered how it worked, how you dealt with it. I heard, one night as I passed along Westbourne Grove, a man telling another man that there was no need to worry. The first man was blowing great clouds of smoke; his companion slouched upwind.

The second man, trembling, said, do you think I’m unaware of the hunner fifty I owe you?

The first man turned away and said, I oughta gut you.

All four Jacks? asked the second man. I was supposed to see that coming?

The first man scowled and gave out the badass glare.

On a bitter, rainy afternoon, I want to a concert at St. Peter’s church hall. The concert was six pieces for solo piano. I sat next to a young mother and her child; the mother provided a whispered commentary. This music, she told her child, is from France, which is a country on the other side of the ocean. They speak French there and drive the most beautiful cars. Matisse and Simone DeBouvoir, she said, are French. Bridget Bardot too. And Maurice Chavalier. She made it clear that the woman playing the piano didn’t write the music. The music, she said, was written by Chopin, Debussy, Poulenc, Satie and Faure. She said the names as if reciting a poem.

Now, 38 years later, I remember nothing specific, only impressions; the woman’s pale green coat, the tranquil shimmer of the music, the smell of wood polish and damp wool, the rapt attention of the audience, the intricate parquet flooring, the dull blue of the walls, the pianist’s exact fingers, her straightened hair and black eyes, her ballet slippers, and a poster on the wall that said, Make Unto The Lord A Joyful Noise.

I remember a younger summer spent laying near the public baths within the shadows of strangers. Wanting what most people wanted but having no idea how to get it. Thinking myself a part of something bigger, something vital. A city boy now, a dreamer, at home amongst the buyers and havers, the recently birthed believers who ran the show, who preformed dull miracles, who eagerly participated, who understood. And thinking how, after dark, in still peopled parks, no one wanted to go home.

All these memories blow around me as I walk the hills where I now live. What happened 40 years ago and what’s happening now. Birds and sheep and birch trees mingle with Kilburn and Kennington and long nights at soul and reggae clubs. I come home and play Catch You On The Rebound by Brenton Wood. It’s a song that I’ve always loved; I feel like it’s trying to teach me something. I’m not, however, a good student. The song is about the temporariness of hurt, the impermanence of all things, the flux of life. You get hurt and then everything that happens in a life happens and you meet it all again on the way back. And you do it smiling. You do it without anger. You do it like Brenton Wood did it; you get up, dust yourself off and say, catch you on the rebound.

*

You can follow the Jeb’s Jukebox Spotify playlist here.