In an extract from work-in-progress ‘Tenderfoot’, JLM Morton tells the story of a forgotten river.

the river can make you good

~ Natalie Diaz

This is a story of a river. Not a mighty, noteworthy river like the Amazon or the Nile or a river that stabilises the global climate and sustains millions of lives.

This is a story of a river that goes unnoticed. A modest river that flows south-east through the Gloucestershire countryside rising on the limestone escarpment above Cheltenham Spa and running through villages, farmlands and the wetlands of the Cotswold Water Park before feeling its way over the border into Wiltshire and joining the Thames at Cricklade. It is a country river folded neatly away in the landscape, tucked under culverts, tunnelled through high banks of vegetation in summer, slipping through water meadows, running parallel to dual carriageways behind dry stone walls, coursing through private estates and exclusive fishing grounds. It is a river whose very existence has been contested. Perhaps unsurprisingly then, no one who doesn’t live locally has heard of the Churn. When I mention it, people respond without recognition.

Ghost river.

River ghost.

Yet however small or insignificant or unknown, this river is a home to me. It has taught me that it’s possible to feel deep connection and kinship with a river, that it’s possible to find solace and joy and comfort in a waterway, a fluid element that’s always already elsewhere, reinventing itself again, repeating itself over and over.

~ ~ ~

The source of the Churn rises at seven springs clustered close together along a gently curving line in a bowl of ground, just below a layby off the A436. A tall dry-stone wall has been built around the source, bulwark against a bank of earth, with alcoves for each spring tucked into the base. Rough cut steps lead down to the water, overgrown with moss and ivy and scattered with starbursts of celandines and daffodils.

The water is cold and pristine, so crystalline the earth could be exhaling light, beaming lasers past bryophytes, tender liverwort and a tangle of last year’s leaves. I close my eyes and feel the aliveness of it, can almost hear it breathe, before one lorry, then another, thunder by, overpowering everything else.

There is a wide sweep of ground for the source to rise on, but it’s been a dry year so far, and the water is shallow and no broader than a meter where it flows briefly over a honey-coloured limestone beach before disappearing into the concrete culvert that takes the young Churn under the main road.

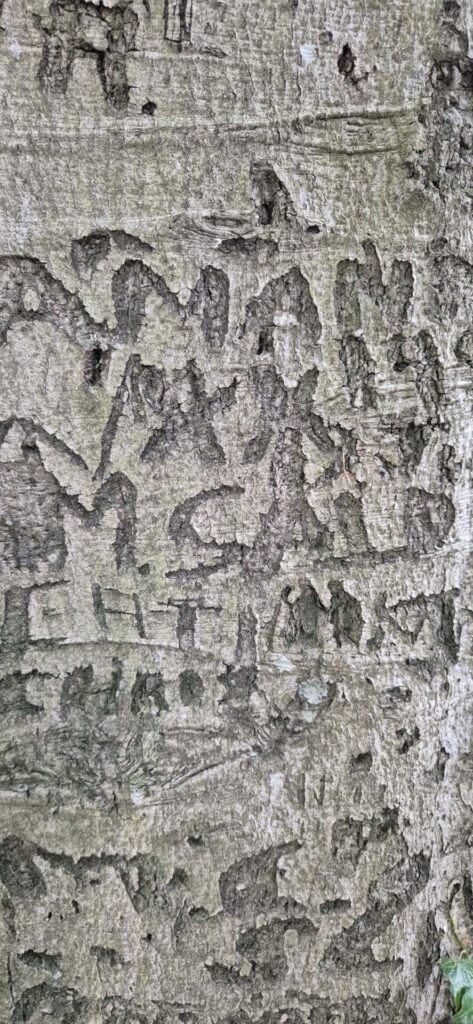

I jump on the steppingstones, snapping spent beech nuts underfoot and clear some litter from the area — cans, plastic, a barbecue charcoal bag. Seven Springs is used now, as it may always have been, as a site of ritual and remembrance. A safe place to gather just off a very busy road, these days it is a shrine to those who have been killed in countless car accidents along this stretch between Seven Springs and Ullenwood. Young men mainly, memorialised in framed photographs placed near the springs or in messages sealed in cellophane and attached to long-dead bouquets. Initials are deeply carved in a mature tree overlooking the source. People bring offerings and libations, ashes to scatter, pausing for a while with their thoughts and watching the water, distracted, leaving their rubbish behind. On my latest visit, I find red rose petals strewn and snagged round the springs.

I return up the steps and take the curving path round the layby. Waiting for a gap in the traffic, I scoot over the road and scramble down a scrappy verge of nettles, ash and elder and peer over the mess of crumbled wall and barbed wire to see where the Churn emerges from under the road and out the other side. It empties into a stagnant, deep green pond fenced off in the garden of the Seven Springs Pub. I jog back along the road’s edge to see if I can get in for a closer look, but the pub is closed, possibly permanently, faded posters advertising meal deals peeling off the inside of the windows.

~ ~ ~

It had been grief that brought me home for good; and before that, a sudden decline in my father’s health. From the top floor, I could see the grey outlines of hedgerows, fields and the rooves of the Bowling Green estate through the condensation on the glass. The orange fuzz of a streetlamp outside. I shoved the window open with the heel of my hand, unsticking white paint from the frame. Cold air and the faint smell of lowing cattle rushed in from the meadows abreast of the River Churn below. I hadn’t stayed there for years and yet that view, that looking, was as familiar to me as a well-worn path.

I visited Dad in hospital for the first time. Admitted in an ambulance sent for by his GP, he looked thin, the clear blue of his eyes startling against the line of his black lashes. He still had that hollow look to him that I’d seen on his birthday three weeks before.

My brother and I sat either side of his bed. We’d brought newspapers and magazines and we stared at each other, our eye-lines disturbed by the urgent comings and goings of the unit. It was the first time for decades I’d seen Dad out in the world, not at home, around a table. I felt I needed to interpret it for him, keep him safe. I realised that I didn’t really know him at all.

There was something childlike about his face that night. A man who lived alone, worked alone, dined alone, drank alone, thrust into the official world of the hospital with its ECGs, saline drips, privacy curtains and nurses busy with drugs and charts and equipment. All that sudden activity in a life so permanently quiet.

~ ~ ~

Two signs have been erected at Seven Springs. One is a stone plaque set into the headwall of the culvert overlooking the source. The carved Latin inscription reads:

Hic Tuus

O Tamesine Pater

Septemgeminus Fons

Translated, the text reads: ‘Here / O Father Thames / is your sevenfold spring.’ The plaque is signed with the mysterious initials T.S.E.. The river’s name is believed to be derived from the Proto-Celtic word ‘tamēssa,’ meaning ‘dark’ or ‘dark water,’ referring to the rivers’ appearance. This word was later adopted by the Romans as ‘Tamesis,’ a name still commonly used by locals.

The other sign near the top of the steps to the springs is a white information board, sheened with algae, installed by Coberley Parish Council. The board thanks its sponsors for work carried out to restore the dry-stone walling around ‘this natural history landmark,’ and notes that:

despite the controversy over the years, Seven Springs is certainly one of the sources of the River Thames and is held by many to be its ultimate source.

What authority the many have to the claim isn’t revealed, but the board goes on to state that the waters at the official Thames Head rise only seasonally — a winter bourne — whereas those at Seven Springs ‘flow throughout the year:’

The Thames / Churn river may, therefore, be regarded as the longest natural river flow in the United Kingdom, beating its nearest rival, the River Severn, by some 9 miles.

As if the text itself weren’t plain enough, the word beating seems to drive home the intent, to lay claim to the longest river in the land. Beating like a heart striking against a breast. River as a pulsing life force, the clear blood that connects these humble springs to the mighty Thames.

The name ‘dark water’ seems well suited to a river that’s almost been forgotten (the Churn) and become so evocative of our collective memory (the Thames). The Thames is a river so deeply held in the English imagination. It has nourished and shaped the country’s now faltering status as a global power, as well as its vision of itself as the green and pleasant land of children’s classics like Wind in the Willows, which is set in the Thames valley. Defence and boundary, this powerful river is liquid history, circuitous and looping, symbol of redemption and renewal, brown god and pastoral idyll, emblem of abundance, trade and influence. Small wonder Coberley Parish Council has been so eager declare the Thames their own.

~ ~ ~

The desire to claim and control natural resources has surely been a cause of conflict since humans learned to punch each other with their fists — and water wars loom as a likely feature of our future. If you walk along the A436 from Seven Springs and take a right toward Crickley Hill over the fields, you will soon find a site of great antiquity. Archaeologists have found the earliest evidence there of a battle in Britain, c.4000 BC, fought with flint arrows and spears on this extraordinary vantage point overlooking the floodplain of the Severn, south-west towards the Bannau Brycheiniog and the Black Mountains, and north towards the Malvern Hills.

Looking out over the escarpment towards the Malverns, I remind myself I’m one of a new generation whose relationship to the land has been shaped by different forces. On an evening in May 1992, we crested the brow of those hills at dusk and descended the other side. We saw the twinkling lights spread out between the vehicles and sound systems on the common below with an anticipation that was electrifying. All talking at once, rolling fags, hanging out of the car windows, we found a spot to park up off the B4208 and entered three days that would change the rest of our lives forever.

Party-goers stumbled around saucer-eyed and gurning, my brother was mugged almost as soon as we arrived, the site was used as a toilet and people threw up in local gardens, creating tension between ravers and the travellers who respected the land and had learned to protect their culture by keeping proceedings tidy. Castlemorton rave was rough and lawless, a ramshackle sprawling convoy of horse boxes, caravans, coaches, tents and cars, but it was also pure groundbreaking magic. Us bored rural kids were excited, proud even, that something this big was happening round our way.

It wasn’t my first free party – there were plenty more (Stroud, Lechlade, Acton, placenames I can’t now remember) — and it wasn’t my last, but immersed in the trippy euphoria of the sound — DIY, Circus Warp, Spiral Tribe, Bedlam — dancing all night with a nomadic, open, inclusive community of like-minded souls, the seeds of a sensibility that belonged to a wild land beyond the urban norm were set for life.

Castlemorton festival was a landmark in ‘90s free party culture, the last major youth movement before the digital age and one that connected music with environmental consciousness and community building and questioned laws on trespass and land access. I thought I’d left my raving days behind, but the memory of a kind of carefree daring flickers in my bones on that day at the source of the River Churn. And that flickering flares into a flame as I jump the fence that encloses the Seven Springs pub and take my first of many steps as a trespasser along the 23 miles of the river, looking for a line in the overgrown grass where the water drains out of the pond, tugged along by the certainty of gravity.

~ ~ ~

As I spent the winter watching my father die, the Thames connected us. Its churning lower course flowed through London, where I lived, from the source which was just a few miles from Dad’s home and where his ashes are now interred on the scarp. Water runs through my family tree, an element connecting me to the relatives who died before I arrived, the uncles and ancestors I never met who worked as stevedores on the Thames at the London docks, and to my grandfather who kept the lock at Sonning. My dad was a legend in the family for swimming the English Channel smeared in goose fat and for steering a sailing boat over the Irish Sea through a severe storm, lashed to the wheel. Whether true or apocryphal, these tales have taken on the patina of historical fact in the family record, saying something deeply felt about who we think we are as a people. In the midst of quite an ordinary upbringing this was a kind of origin story we told ourselves, as if our bloodline were something hallowed. Maybe even as precious and potent as the Thames itself.

~ ~ ~

In February 1937 Hansard records MPs debating the Thames source in Parliament. William Morrison, Minister of Agriculture and MP for Cirencester and Tewkesbury where the Thames Head is located, insisted ‘leading authorities agree that the name of the stream which rises at Seven Springs is the “Churn”’ and that under no circumstances could a change be justified.

Sir Robert Perkins, MP for Stroud, countered that Seven Springs is twice as high above sea level than Thames Head and farther from the estuary, to which the Minister reiterated that the Thames rises in his constituency.

Lord Apsley, owner of the Bathurst Estate and land which surrounds Thames Head, pointed to the ancient origins of the name Churn as an assurance of its provenance. Then, making a wildcard intervention, Apsley suggested the real Thames is a stream called Will-brook in the constituency of the ‘honourable and gallant Member for Chippenham, Captain Cazalet.’

Evidently no definitive conclusion was reached in this obscure political game of cat and mouse and the issue does not appear to have been debated again in Parliament. The Ordnance Survey continues to mark Thames Head near Kemble as the source, and the controversy continues to ignite local passions, illuminating a long and ongoing impulse to name, claim, cordon and control.

~ ~ ~

I stood, leaning over the bathroom sink in my rented maisonette in Peckham, getting ready to pack my bags and set off to find Dad in the obscure cottage hospital he’d been transferred to. I thought about how there is only as much water as there will ever be on the planet as I watched it spiral down the plughole.

The spiral, an image prior to language. Felt in the body, in birth, in life, in death and rebirth. An ancient geometric shape and such a common pattern in nature, found in mollusc shells, pinecones, winding through the heart of our galaxy.

A line and a circle, looped in ever increasing or decreasing circumference, representing expansion and contraction, a journey outward and inward, a quest as well as a homecoming.

Like grief, it is determined and equivocal, a shape that shifts and turns; like the ghost river that haunted me and still haunts me. Like the spiralling water that draws me onwards and will not let me go.

*

JLM Morton’s debut poetry collection is ‘Red Handed’ (Broken Sleep Books, 2024), a Poetry Society Book of the year. Her new pamphlet ‘Forest’ tells the tale of the black pine, first tree to arrive in a woodland (Yew Tree Press, 2025). She is currently writing her next book with the support of an Authors Foundation grant from the Society of Authors. Juliette is based in the West of England, where she lives with her family. Find her online @jlmmorton / www.jlmmorton.com