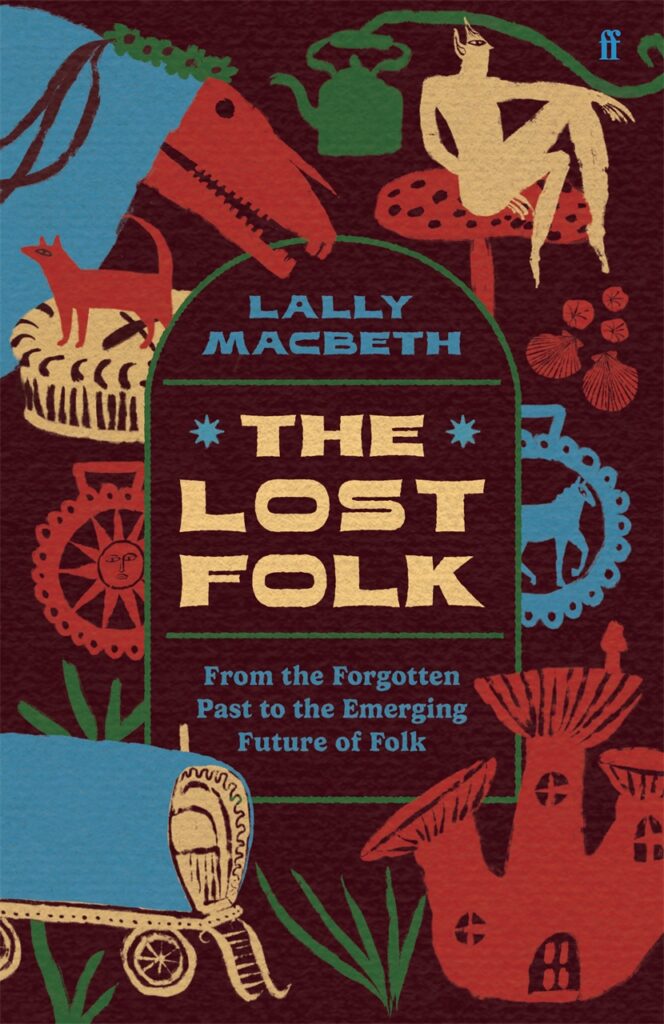

Published by Faber, Lally MacBeth’s ‘The Lost Folk: From the Forgotten Past to the Emerging Future of Folk’ is our July Book of the Month. Sophie Parkes reviews, finding an attentive author who not only cares deeply about folk culture, but also the people who create it.

The profile of folklore in the UK, and the accompanying interest in folk culture, has never seemed higher. Designer and director of the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, Simon Costin, in an article for The Sunday Times last year, expressed that folk culture is ever present, constantly evolving; it is simply our attention that fluctuates. ‘Any idea of revival is wrong. It’s a revival of interest,’ he said.

It may seem odd, then, that a book should be published in 2025 on the ‘lost’ aspects of folk culture. With young people reinventing traditional song, dance and custom to reflect their own twenty-first century concerns; with folkloric motifs being adopted and critiqued by contemporary television, film, and literature; with documentaries on the radio and television interrogating folkloric matter, surely there are more ‘found’ elements of folklore for us to be content with, ripe for reinterpretation?

Instead, Lally MacBeth succeeds in highlighting elements of folk culture that are frequently overlooked, and offers reasons for their marginalisation: the culture expressed and favoured by women, by migrant and diasporic communities, the domestic, municipal, quiet, eccentric, mundane, difficult to categorise. The significance of the church kneeler, which frequently appear on her Instagram account, The Folk Archive, is particularly well espoused, and deplores their invisibility or their utility as sandbags. Church kneelers are the epitome of MacBeth’s folk: created by (anonymous, likely female) hand, depicting scenes from daily life, publicly accessible but hugely undervalued. The Lost Folk, and MacBeth’s attentive eye, asks us to lean in, look closer, and appreciate. At times, though, it can feel a little like a roll-call of collectors, collections, customs: examples described and clearly admired, but with the book’s broad remit – the wide palette of folk culture she chooses to examine under the microscope, across the entirety of the United Kingdom – there is little room for in-depth analysis. What is the impact of the shell grotto, for example, and its apparent demise? What might a twenty-first century equivalent be? And why should we care?

Caring about folk culture is at the heart of The Lost Folk. MacBeth, understandably, mourns when a collection is consigned to the skip, or split between institutions on the death of the collector, or when a custom is no longer practiced, and the reader is entreated to grieve with her. But, at the risk of sounding uncaring, this is the cycle of folk culture: if a garden of topiary sculptures is not worth the upkeep in time and resource to the community it previously served, then it will be lost. Of course, it is particularly galling when there is a campaign to retain something and external forces – money, red tape, a lack of specialist knowledge – make this an impossibility. In our increasingly homogenous world, the value of something ‘touched or made by the human hand’, as MacBeth defines folk, may well be under threat. Perhaps, then, is the need for robust ‘documentation’, rather than the outright ‘preservation’ that MacBeth advocates. To my mind, The Lost Folk is doing the job of documentation well: giving platform to people and their practices, and, significantly, reiterating the desperate need for the recognition (and contribution) by people outside of the (current) canon.

MacBeth therefore, and rightly, cares about the folk themselves, and seeks to ensure that diverse folk practices are regarded on an equal footing to the historically accepted. She offers the example of Polish communities in Devon and Wales that have been quietly holding traditional dance evenings and decorating their community hubs in Polish traditional art since the Second World War. ‘In the case of migrant communities across Britain,’ MacBeth writes, ‘folk customs also offer a way of a community finding a new home and feeling settled – a way of laying down new roots’. Though folklorists and anthropologists may have been documenting instances like these for years, it is rare that they are acknowledged by the wider cultural milieu as part of the folklore of England, or Britain. This is welcome advocacy.

MacBeth’s desire for preservation seems to be confined to material culture; in ‘The Lost Customs’ section, she acknowledges the need for customs to evolve in line with individual and community need, again a symptom of the care at the book’s core. ‘If they want to hold their ceremony on that day rather than this, or wear this costume because it’s more comfortable than that old scratchy one that needs to be dry cleaned, or hold the festival outside rather than inside, or vice versa,’ she writes, ‘then that is perfectly legitimate. They are the people carrying on the tradition. They are the folk now’. Custodians of customs that refuse to evolve away from harmful practices, such as those with obvious links to minstrelsy, are condemned. Here the book is a companion to Liz Williams’ Rough Music (Reaktion), published only months before. Though MacBeth must tread carefully, as there are times when the book appears to support the survivals theory purported by the antiquarians-turned-folklorists of the twentieth century which, in summary, makes links between pre-Christian and contemporary folkloric practices. In reality, our folklore, and our customs in particular, are rarely as ‘ancient’ as we think (or hope), and though this theory abounds in lay explanations of our folklore, it has widely been discredited in academia.

Written in a genteel voice, The Lost Folk is personal. MacBeth’s charity shop finds often start or augment the search. Detail is supplied by her correspondence with the relatives of collectors, or photographs supplied by friends. Newspapers are scoured; old books consulted. Her encounters with folk culture are sometimes accidental, and not always straightforward, ‘I don’t drive and am often reliant on public transport or lifts, which can be hard to come by when the words “model” and “village” are mentioned together’. Her obvious delight in her discoveries are enjoyable to read, written so that we may follow in her footsteps – ‘I want everyone to get a chance to spend an hour or so as a giant’ – though she does warn against turning up en masse to the more photogenic and Instagrammable customs, instead inviting us to revive lapsed customs or start our own. This personal approach, and this encouragement to participate, makes for engaging reading and a useful way into this vast, appealing subject.

*

‘The Lost Folk: From the Forgotten Past to the Emerging Future of Folk’ is out now and available here (£19.00). Read an extract from the book, on model villages, here.

Sophie Parkes-Nield is a folklore researcher, creative writing lecturer, and, writing as Sophie Parkes, a novelist, short story writer, and music journalist. She is currently working on the AHRC funded National Folklore Survey for England project. Visit her website here.