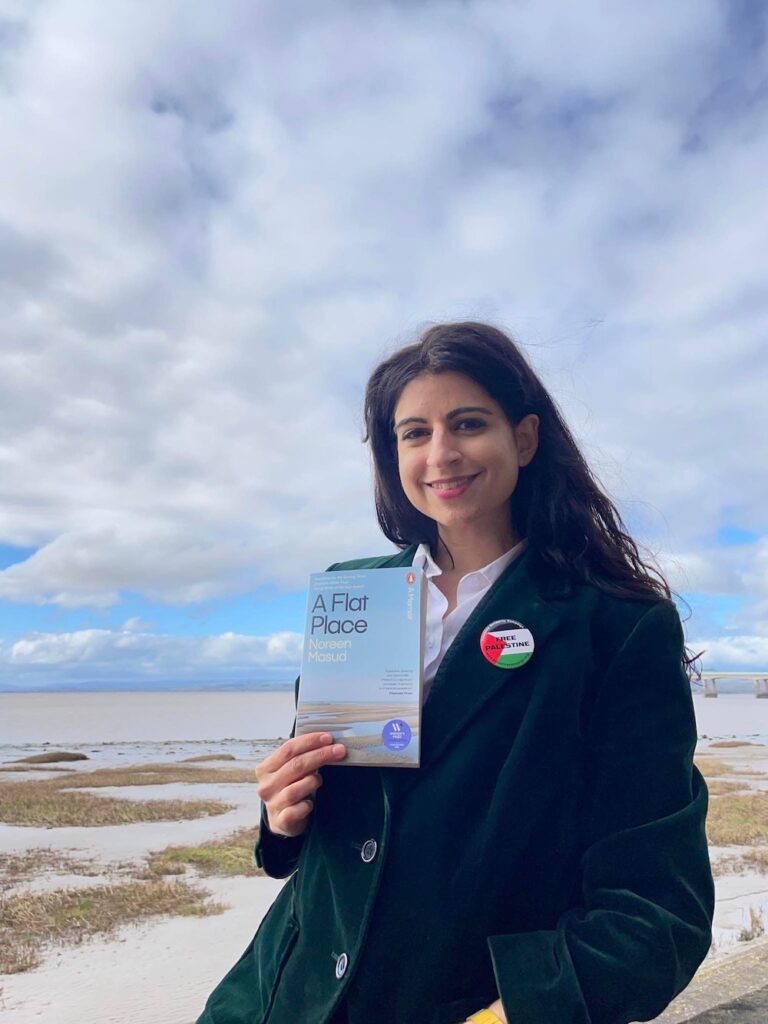

More than a year on from the publication of her acclaimed memoir ‘A Flat Place’, Tallulah Brennan speaks to Noreen Masud about the mystery of flat landscapes, the current state of nature writing, and the book industry’s reticence to support Palestinian liberation and fossil fuel divestment.

In the introduction to your book A Flat Place, you reference Virginia Woolf’s childhood memory of St Ives which has shaped her life: ‘If life has a base that it stands upon, if it is a bowl that one fills and fills and fills – then my bowl without a doubt stands upon this memory.’ I was wondering if the book has in any way become a part of the base that your life now stands upon? I don’t mean in the sense of any wealth or profile it might have brought, I mean in terms of making sense of your past, of flatness, of Britain or Pakistan, even. Over a year on from it being published, how do you feel that the book has shaped your life, and continues to?

Such an astute question. I love what you’ve picked up there, the possibility that foundational images and ways of thinking could change. I think that’s so important. So beautiful right, the idea that we are so much less fixed than we think; we are so much a composite of the people we’re around and what’s going on in the world. And of course, we are changed by practical, political things like whether we have access to what we need. Even after I’ve talked about the book so much and with so many people, the image of a flat landscape still feels like a mystery to me that I will never finish plumbing. So in that sense the base is the same, but, previously, I suppose it would be fair to say the base felt totally private, totally unsharable. What was unexpected about the book was first of all that I was believed. I had the experience of being believed by my publisher and by my readers, and that was transformative. That allows you to have faith. But also I have had emails and messages from people all over the world, some women of colour, but also people utterly unlike me saying that they found something in the book that resonated in some way. Still it’s the lesson that we all as humans have to learn, again and again, that what seems totally unique to us is not. And so I suppose, as I hint at the end of the book, though the base, the flat fields of Lahore, Pakistan, may remain the same, the kind of feelings that attach to it soften, they may be less stark and heartbroken.

In the chapter on Orford Ness, a place associated with war stories, you wrote: ‘Your mind bends back and down the paths carved out for it. You find yourself, always, telling a story you already know. You register it, like a rubber stamp coming down, and you move on.’ You say you feel you have nothing to add, because here is a place ‘written over, again and again, by other people’; it is ‘white male memory… bombs and drama’. How do you relate this to the current state of British nature writing, or people writing on their environment full stop? Put straightforwardly, are you finding yourself bored with the state of nature writing?

Yes! Nature writing, in the way that we understand the term today, is one of the most rigid genres. I will say that there are people doing interesting things with nature writing. I think that Polly Atkin’s Some of Us Just Fall is really interesting. I just read Jenn Ashworth’s, The Parallel Path, which, like everything Jenn Ashworth writes, is fresh – she could take the most burnt out genre and make it zingy again, right? One of the things shadowing this conversation is the recent exposé of The Salt Path. You know, the heavily implied nature cure narrative, the walk-a-100-miles-to-cure-whatever-incurable-disease is what sells. That book was a bestseller, because these ready-made stories are comforting, and people like to read more of what they already know. People think they want newness, but I think as human beings often we find newness very challenging. The mental demand that it makes is often something we feel, rightly or wrongly, that we don’t have the energy for. People like treading the same paths again and again, they like being told things they already think. So it’s a particular obstacle for me, because I have skin in the game. As the book implies, the stories that have already been told about women of colour, they might be comforting ones to white people, but they are not comforting to people like me. And so, it was really important to me, as I wrote this book, that I not re-inscribe the Islamophobic narratives around South Asian women’s lives, and particularly about Muslim women’s lives. I was wary of the kind of rigidity of the stories available to me as a ‘nature writer’, but also as someone writing about a difficult childhood that happened to me, that was a Muslim childhood and a South Asian childhood. But yes, to return to your question, I am bored!

There’s something almost anti-ambition about the book, which I think feeds into this too. ‘Not all discoveries involve digging… or ascending heights’, you say. A moment that really stuck with me is when you’re happy admitting you do not know the name of certain shells, or you’re happy that what you saw could have been a red backed shrike ‘or almost anything else’. You state that you’ve never been good at reading maps either. These statements read as simply neutral observations about your limits. You might be able to help me think this through, because I have a strong sense that this is linked to the effect a mountain can have — ‘How cruel, to instill the belief that one must always be striving’, as you so astutely write. So, how do flat landscapes affect your writing in this way? Do they assure you that there is no conventional standard to rise to, or do they drive you towards something other than the ambition of comprehensive, exhaustive knowledge of nature? Would you like to see nature writing freed, in some way, of ambition?

There is a lot to say on this question. The first thing I have to say is that I massively respect expertise, in an age where expert knowledge is really under threat. All power to people who know things. At the same time, I suppose what was interesting to me as I wrote the book was, what are our intellectual options when we’re faced with something we don’t understand. What are the ready-made paths available for how we deal with the world in front of us? One of those of course is to name. It’s about assimilating the world to the kind of modes of relationship that fall easily to hand. Naming is comforting, it makes us feel like we are in charge, like we know the rules of this game. One of the things I find so fascinating about a flat landscape is that it’s an encounter that completely, I think, scuppers the rules of any game we might try and play with them, because it’s nothing to look at, or anything you might look at doesn’t matter. So what are our choices? Either we make small things matter or we give up on any idea of mattering. Making small things matter has long been the way people engage with the flat landscape — think of Jon Clare in the fens: ‘Look, you think there is nothing to see, but look at those lovely crocuses!’ Fine, but it’s still the same game. What if we what if we were to imagine a different game? The flat landscape challenges us to do so. It is scary to be vulnerable and not knowing. Let’s allow it to be definitional of itself, to set its own terms. That seems to me an ethical necessity particularly at the moment. We need the capacity to relate that doesn’t slot people and places into predefined experiences. Flat places make you wait a little longer before recognising what is in front of you. How do we care about things that might not respond meaningfully to being variously singled out, named, focused on, assimilated, in other words, to our modes of knowledge? It is a challenge we must face as the climate crisis accelerates. We have to find ways of caring about things and people that we cannot individuate. People perhaps in the future, people on the other side of the world from ourselves, people who look and speak and sound and think very differently to us. We have to find ways of making their suffering urgent to us, and that requires a rethinking of our need to individuate in order to relate.

To go further with the idea of finding and caring for stories we cannot see ourselves in, as people in the Global North, after you discuss your family’s experience of Partition or civil war, you say ‘Why would you speak if you don’t trust anyone to listen or care?’ In so many ways, we have more voices which were once treated with contempt or suspicion than ever in the cultural sphere. In the past couple of years, there have been literary prize nominations for Palestinian authors, the Wainwright Prize was awarded to a book on migration, belonging and nature in Britain, your own book was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize, for example. Yet we also are witnessing a genocide which has resulted in the countless deaths of writers, artists and journalists, and Britain is witnessing another peak in its identity crisis, and one which is becoming increasingly violent towards people of colour. I was wondering if you could speak to how this contradictory cultural moment feels to you? Why is some kind of listening accepted, putting a Palestinian poet on your lineup for example, but not a boycott and demand for divestment?

I think that’s a brilliant question. Until I would say the last couple of months, it has felt torturous. I grew up very lucky compared to people around me, in terms of my access to books. I took very seriously the idea that books could change the world. Books in Pakistan when I was growing up, that’s where there was the possibility of non-sanctioned knowledge. I found the possibility of different worlds and different perspectives and different ways of doing things. It was an absolute tenet of my youth that what you learned you did something with. If you learned that things were wrong, it was your duty to make them different. It comes back to the fact that it is the things that seem simplest that are the most difficult — to act on what we know to be true. This moment has shown us people find it impossibly difficult. But I continue not really to be able to do anything else; it is a rigidity in me. And so, when I organise with Fossil Free Books, the line on every side in order to try to smear us, sway us, discourage us, intimidate us, was: ‘you should come along to the festival to debate, you shouldn’t seek to endanger the festival because books change the world.’ And I thought, what an appalling insult. What an insult to celebrate books, and reading and knowledge and yet not act upon what they are telling us to do. What is a book then? It becomes something masturbatory, it becomes mere fantasy. I take that very personally because I think that writing is very important. In the case of the book industry, there is an extra level of righteousness and a sense of moral superiority because they think books are intrinsically a good thing, or that reading makes you a better person. I’ve worked in many English departments, and I can very confidently say that reading doesn’t make you a better person.

It has taken until now essentially for the cultural industries to be lined up in condemnation. What has to happen though is for writers to understand urgently that their responsibility to the world now is not as writers necessarily. It’s not necessarily to write yet another beautiful poem about how bad everything is. It is to do what is boring, to do admin, it’s to have hard conversations with people, it’s putting out spreadsheets, it’s doing what needs to be done in order to hunt down the money. The reason the genocide goes on is because it is politically and financially expedient for our government, and the only theory of change I have access to is that it will not stop no matter how beautiful our poems are, until we make it more expensive and difficult to support the genocide, until we make it a poor investment, it will continue.

Yes, and the reality is that it can continue because there is little acknowledgement of Palestinian humanity — as you question yourself, ‘…was it just accepted that some lives could, and would, and should expect to hold more pain than others?’ When you wrote this, I assume you were not thinking of how this might manifest in the book industry, but maybe you were, and if so, how do you think this applies in your writing, but also in the industry generally? Have you felt it resonated in your collaborations with Fossil Free Books?

I write in a piece I did for Tolka Journal about how relieved I am in a way but my book came out that year, and not so the year before. Say it was a year before the genocide started, and I had the book industry coming to me and being kind, and making friends with me; it is very hard to criticize people you are friends with. By the time A Flat Place was longlisted for the Women’s Prize, and certainly by the time it was shortlisted for it and other prizes, I had already seen the book industry’s response to the genocide, so I knew the limits of the praise. And thank goodness, because I am a weak human being, I’m a flawed person, and I would probably have done what is expedient, because we’re all so much weaker than we would like to think. But it was unignorable because of the timing.

In Isabella Hammad’s Enter Ghost, she writes, ‘Haneen once compared Palestine to an exposed part of an electronic network, where someone has cut the rubber coating with a knife to show the wires and currents underneath. She probably didn’t say that exactly, but that was the image she had brought into my mind. That this place revealed something about the whole world.’ The idea that the conflict in Palestine is a litmus test for all of humanity, an experiment in how much suffering we could accept, or how much can be tolerated, is gaining traction. Yet, at the Society of Authors, the largest writers’ union, a resolution for fossil fuel divestment was accepted, but not the call to make a statement demanding an end to genocide in Gaza. Clearly, many people are still ignorant of the way these issues are connected, something FFB has been persistently making the case for. How do you think this separation of struggles is still possible, and does this surprise you from this industry? What has to happen to keep people tying these things together?

It’s a bigger thing than I have the kind of capacity to talk about usefully. I think when there is a social consensus, it is incredibly difficult to speak against it, and it is incredibly dangerous to let yourself see what your community — your intellectual community, writerly community, your family and friends — what they do not want to see and are not able to see. It’s incredibly risky to see that. And what do people have to lose? A lot. Us at Fossil Free Books have lost jobs, community, and gigs, and many have been seriously harmed financially and emotionally by the media lies. It doesn’t matter about being right to most people, or about doing the right thing, it matters that the people you respect think you’re doing the right thing. You know it’s very middle-class-acceptable to say that climate change is bad. Until very recently that was not the case for affirming solidarity with Palestine, that has been cast as a fringe view.

I think it is a really normal experience for even very intellectual people to live inside cognitive dissonance. It’s better to live inside cognitive dissonance than to take the risk. We’re just such profoundly social animals, and we have to understand this, we have to understand it is much more useful to acknowledge the reasons which are to do with being a kind of normal, frightened, flawed human being. Reasons which lead people to not see or not know what they perceive as dangerous to see or to know. We have to acknowledge that and we have to work with that if we want to change minds. We have to take a deep breath and say, whether we like it or not, this is how people work.

I mean it’s the case at the moment that our writers union, the Society of Authors, is a fairly conservative organization. It’s pretty invested in the status quo, because the status quo mostly works for it as a largely white, middle-class organisation. But the status quo is fundamentally built on genocides, historical and ongoing. It is so frightening how security should make people brave but it makes them cowardly, and I think constantly about the connotations of the phrase cultural capital. As I believe with all capital, one should not hoard capital, one should give it away, one should allow it to flow back into society. I’ve gained a little bit of cultural capital with the publication of A Flat Place and the generous reception it received, and it is my job then not to hold that capital but to put it on the line in service of what needs to be done. What could it possibly mean to write about the degradation and sidelineing of, specifically in my case brown bodies, and then not give away that capital in service of campaigning to make things better?

‘What does my private experience, [my] transformational experience of reading a book have to do with snipers in the West Bank?’ is what Lola Olufemi suggests Fossil Free Books have to answer and make clear. I think the publishing industry really relies on an often false, romantic idea of reading, and memoir and nature writing is perhaps the most obvious avenue for that. I thought your line ‘I’d rather be grief-stricken than feel unreal’ applies perfectly. Peter Riley, who wrote Strandings: Confessions of a Whale Scavenger, calls for the disavowal of ‘fictions of purity’ about nature, and most importantly maybe, nature writing itself, which is something I see clearly in A Flat Place. Do you feel that some writing does have a sense of being ‘unreal’, and is this why you wrote the book in the way you did? If you do feel that way, then what are the ways in which you find the industry perpetuates this romantic distance-making?

To start with what is closest to hand for me, to be racialized, to be minoritized, to have grown up in the Global South, and to have been educated under a colonial system, is always to be told that what is happening to you is not real. That you are not real, that you are a shadow. It is a commitment that I made to myself whilst writing A Flat Place that I would honor myself to be as real as I possibly could. The real and the unreal are adjudicated by the capitalist, or colonial world. One of the things that happens, if you don’t trust anyone to hear, to come back to the line you quoted earlier, is if there is no chance of you ever getting people’s approval, you have nothing to hide anymore. It is freeing, you just say what is true. But this is a definite shift in nature writing. The book I mentioned earlier, Jenn Ashworth’s The Parallel Path, about walking the Coast to Coast, something goes very wrong in that book, and that shows we are in a new place in nature writing.

We talked about wanting what we already know. We want this careful balance between what we already know, the path that’s ready made, with a tiny little tweak. You want the tiny little variation, what Freud might have called the narcissism of minor difference, that if you change one thing it’s fundamentally different. To keep the kind of machinery of aspiration and desire in motion, it is always a complex of the real and the unreal. I think that the book industry does not like to acknowledge the the conditions on which it is built, the way that many of our publishers are owned by like massive conglomerates, the way that our major book selling chains are owned by awful people, the way that bookselling is so dependent on Amazon, which is a tremendous evil in the world. Just one example is that whenever I meet a bookish person, they’ll look at my book which is folded over, and dog eared, and things are ripped out, and they look horrified. And I say to them, do you know how many books are pulped every year, because no one wants to buy or read them? Our fantasy around books and the reality of book production and dissemination is so wildly separate. It’s in the book industry’s interests to maintain and pretend that the tremendous aura and specialness of the book. It is something for you to read and use and act upon. That is the beginning and the end of its realm. It is not something sacred.

The real and the unreal in nature writing is so interesting because to touch grass, to go out and think out in nature, is that a reconnection with what is real and what is most important? Or is that a running away from what is real? What is real? Is it the videos of children being disemboweled in our phones or is it the unspeaking grass in our gardens? The answer is that neither is the whole reality. At its worst, nature writing urges political naivety under the guise of an encounter with the real.

Finally, I was thinking of Saaidiya Hartman saying, ‘Every generation confronts the task of choosing its past. Inheritances are chosen as much as they are passed on. The past depends less on “what happened then” than on the desires and discontents of the present… But when does one decide to stop looking to the past and instead conceive of a new order?’ It reminds me of the moment in A Flat Place, in which you are pondering the fens. You write about a place being able to be both damaged and beautiful; ‘Is the life marked by loss? Does the life spring forth from that loss?’ Do you see a way that Fossil Free Books could build a new order, something beautiful and lively out of the violent reality corporate sponsorship has made of the book industry? In the years to come, of climate breakdown, of living in the wreckage of a genocide, where do you see the role of writers in choosing a new inheritance?

Part of the way I survive is detaching my actions from any hopeful result. I say, I do the thing because it is the right thing to do, not because I need to see the result, because I don’t think I will see the result in my lifetime. The result of focusing on the result would be to burn out. Fossil Free Books of course will not build a new order on its own. It has inspired other groups, it will go on to inspire other groups. I find it almost impossible to answer this question because every ounce of me is a pessimist. All of that pessimism must be subordinated to hope. I behave as if there is hope even if there is none, because not to do so is a cognitive dissonance I cannot bear. We at Fossil Free books are encouraging people to join the Society of Authors to make it a union that is truly representative, which can stick up for writers everywhere, including in Gaza. That’s what we as a collective have decided is the next focus for our campaign. To see the role of a writer as something that is not the lone genius at their desk, beavering away, but as somebody whose choices have power over the world, that we must own, and stand by, and behave consistently with.

*

Noreen Masud is an Associate Professor at the University of Bristol. ‘A Flat Place’ was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize, the Young Writer of the Year Award, the Ondaatje Prize, the Jhalak Prize and the Books are my Bag Award.

Tallulah Brennan is a writer based in the North of England, interested in the relationships between humans and their environment, and how they in turn shape each other. She is also a contributing editor at Caught by the River. Follow Tallulah’s Substack here. If you enjoyed this interview, you may also like our bonus Book of the Month interviews for paid subscribers, conducted by Tallulah on a monthly basis. Get a taster here.