Brontës and Boggarts: Jenny Chamarette sinks into Clare Shaw and Anna Chilvers’ (eds), ‘The Book of Bogs’.

Peatlands are one of earth’s most precious and endangered ecosystems. Storing more carbon than the world’s forests combined, they are found in boreal regions and tropics – though substantial areas remain unmapped in the Global South. On the twin isles of Britain and Ireland, as The Book of Bogs states, over 80% are damaged or destroyed. Amassed by peat’s near-magical capacity to preserve millennia-old remains, bogs, heaths and moors are linguistically and culturally plural landscapes. Histories of cultivation, colonial and industrial exploitation encircle them, alongside communities who seek to preserve these places abundant in myth and science.

In the making of The Book of Bogs, Clare Shaw and Anna Chilvers lit a beacon for writers across England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland to assemble their craft in honour of peatlands. Fondly self-describing as Boggarts, they spoke up initially for one localised spot, the Walshaw Moor. Situated between Burnley and Halifax, Walshaw is sometimes lovingly referred to as the ‘Wuthering Moors’, after Emily Brontë’s classic novel Wuthering Heights. The Brontës feature amply: from Claire O’Callaghan’s ‘A Scamper on the Moors’, a literary analysis of Emily’s early eco-criticism, to icons of storytelling in David Morley’s ‘Emily Brontë’ and Ian Humphreys’ ‘The Dog Star Quartet’, or travelling across media and engrained in Nicola Chester’s writing psyche and environmental activism in ‘Wild Moors of the Imagination.’

Many essays, like Mike Mayal’s beautiful cross-genre experimental piece ‘Lystna’, identify that Walshaw is under threat from overseas development as a wind farm. My first uneducated response: renewable energy is a good thing, right? But – what if the revenue generated sits with those who have no ethical investment in the land’s stewardship? What happens to these wild landscapes whose fragile ecosystems perish under man-made development, but which are vital for our ecological survival: flood defences, carbon sinks, thermoregulation? If renewables come at the cost of CO2 emission from disturbed peat, where is the net environmental gain?

Walshaw and its protection are cyclical returns throughout the collection, which represents startling diversity in thinking, writing and being with moors and mires. Bogs are fine drawn through Johnny Turner’s bryology field trip ‘The Little Moss That Stayed’, in Guy Shrubsole’s ‘Make Britain Wet Again’, an investigation into catastrophic moor burns supplying grouse hunts for uber-wealthy landowners, or Melanie Giles’ ‘Moss Fox’, a creative melding of human archaeology and vulpine life. Bog language is as important as place: Robert Macfarlane’s ‘In Which Names Are Spoken’ demonstrates thousands of localised words that map the moors of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Words make stories, and from stories come truths, wrapped in peat.

Boggarts – eldritch bog spirits that come to live in local dwellings – are everywhere. Half my family descends from the working classes of the North West: Jenny Greenteeth and Will O’ The Wisp are embedded in memories of deep slanting rain on Pennine hills. George Parr and Bunty May Marshall bring these centuries-old figures to light in ‘The Call of the Moors,’ on the mythologies that encircle the bog’s deceptive terrains. A boggart comes to stay for one torrential night in Sophie Underwood’s fireside story, ‘What Came Down in the Flood’. And bog spirits are not exclusive to the Global North, as in Annie Worsley’s ‘There Are Boggarts in the Tropics Too’, a geochemistry-cum-autoethnography of her peat encounters in late 1970s Papua New Guinea.

The collection’s four sections track a narrative arc from definition (see Alys Fowler’s gently queer ‘A Peatland Has Two Mothers’) to tension, immersion and, finally, action. Poetry winds throughout, each poem reeling in the anthology’s pulse before sending it on its way. Outstanding examples come from Pascale Petit, whose ‘Bearah Bog’ and ‘Beast’s Castle’ pulsate with life; Patti Smith’s mourning song ‘Death of a Tramp’; and Carola Luther’s Jarman-esque epic poem ‘Descent’, an angelic conversation of the air between bog and wind turbine. Memoir features prominently too, including Amy Liptrot’s ‘Ten Revelations of Peat’, Polly Aitken and Sally Huband’s enjoinder to “believe the ill, or join us” in their cautionary reflection on embodied and environmental breakdown in ‘Conversation Overheard on a Peat bog,’ and Jennifer Jones’ meditation on her in-utero bog-connection, ‘Rooted in Peat.’

And then there is the moss. Sphagnum embraces the book in the photography of its fold-out flyleaves; it lands softly in almost every piece. Like the sphagnum that encases it, The Book of Bogs contains fragile, furious, resilient ecosystems of writing, demanding the protection of a vulnerable environment we need more than we know. Consider it a spell, to encircle the wild peat of your heart.

*

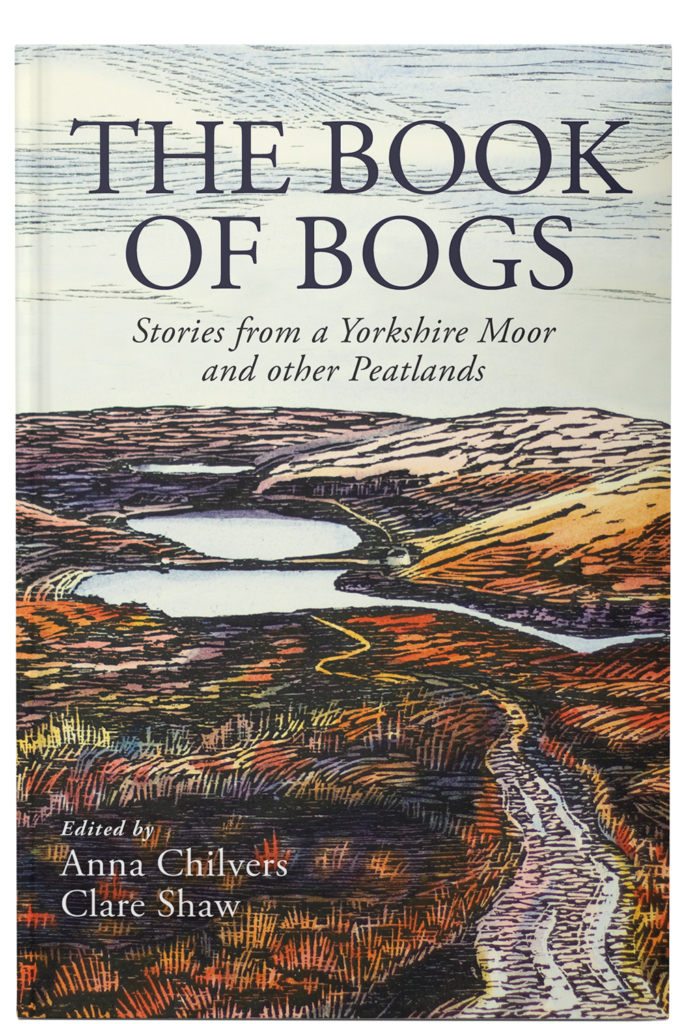

Published by Little Toller, ‘The Book of Bogs: Stories from a Yorkshire Moor and Other Peatlands’ was December’s Book of the Month. Read an extract here, and if you’re a paid Steady subscriber, an interview with its editors here. Buy a copy here (£19).

Jenny Chamarette is a writer, researcher and arts critic, curator and mentor based in London, UK. Shortlisted for the Fitzcarraldo and Nature Chronicles prizes, and longlisted for the Nan Shepherd and Space Crone prizes, Jenny’s non-fiction has been published in anthologies by Saraband and Elliott & Thompson, in Sight & Sound, Litro, Lucy Writers Platform, and Club des Femmes among others. Jenny’s upcoming book ‘Q is for Garden’ explores the radical relationships between sexuality, nature, culture and cultivation.