As he embarks on the writing of his next book, Dan Richards delves into the correspondences of Tove Jansson.

Last week, I caught up with Horatio Clare whilst he was en route to Marseille.

“I’m in a clapped-out Alfa Romeo with an anxious dog”, he shouted above the noise of the autoroute. “Just passed through Arles. I’m probably lost but I’m sure I saw the street of Van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night…”

This is just the sort of chat you want and get with Horatio — traveller, writer, raconteur — and the conversation pinballs between a time spent crewing boats on the Rhône for paranoid Russians, a recent trip to Sicily, moving to France, “well, you know; we thought ‘why not?’”, and ideas for books — he’s just delivered a manuscript and I’m just starting a new book about the things that go on overnight unseen to keep the world safe, sound, replenished whilst most of us are asleep — National Grid workers, Royal Mail sorters, newsrooms, hospitals, freight trains, Samaritans… “Get to the monasteries and fighter squadrons” counselled Horatio. I told him I was planning to go and revisit the Pellinge archipelago in Finland to talk to Marie Kellgren, who fishes in the Baltic around the islands where Tove Jansson wrote and illustrated many of the Moomin books. On a visit in November last year, Marie told me how, when the waters freeze and the days turn dark for months on end, she skates out across the ice on her motorised fan-sled to fish — attuned to the behaviour of the animals above and below her feet; the return of the sun, the slightest hint of thaw. Small wonder that the people of Pellinge celebrate the December solstice with euphoric fires and shindig.

It’ll also be a chance to write about Moominland Midwinter, I told Horatio. “Oh, yes! Fantastic book about the dark. I agree. What fun you’ll have!” Then we spoke about our love of Tove Jansson for a bit before he signed off to motor on south with the dog to the blue Mediterranean coast.

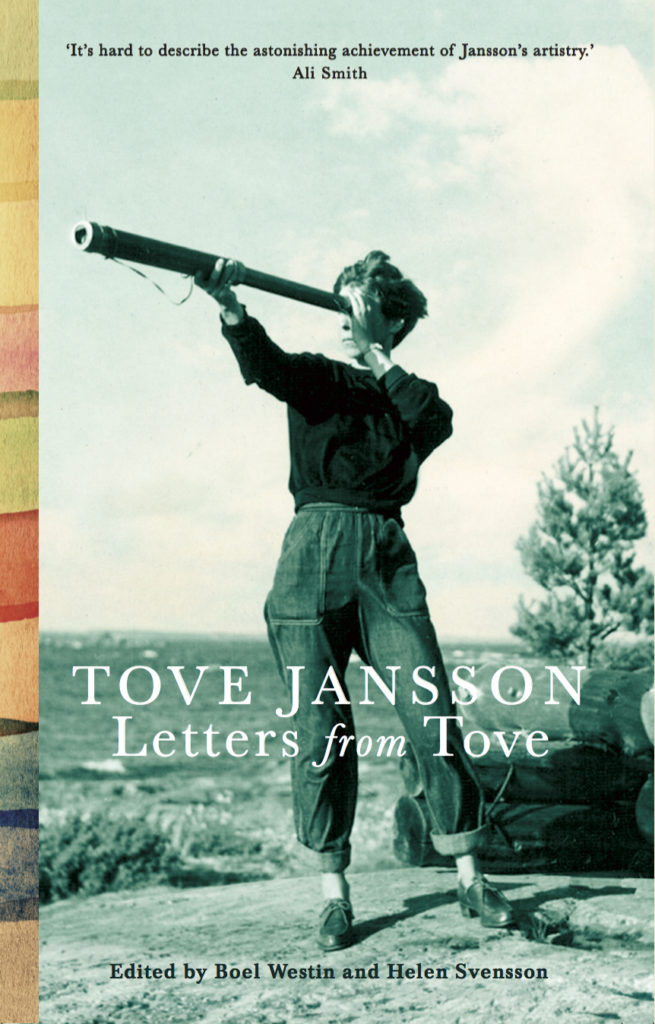

Horatio’s joie de vivre was hard to square with autumnal pandemic Edinburgh outside. The pubs had just closed for a fortnight and the empty early evening streets resumed the hush of anxious April and May. Since March, my research for my Overnight has been very much book-based. Almost everyone I wished to meet was a key worker one way or another so I stayed in one place and read — books about night trains, books about the BBC, books about air traffic control, and Moominland Midwinter, of course, that took me on a most fantastic, frightening voyage. And alongside that, for context and pleasure, I read Tove Jansson’s letters —a beautiful collection recently published in paperback by Sort of Books — chock-full of life, colour, incident and essential optimism — which became something of a light during lockdown. Wanderlust at one remove with added Moomin illustrations!

Here are three extracts, each great in a different way:

1.

Pompeii

June 4th, 1939

The young Tove is travelling around Europe after a time at art school in Paris.

Here, she writes to her family in light of a volcanic adventure:

“Beloved everybody!

I’m lying in bed drinking Cognac Medicinal as the Pompeian moon tips over the mountain ridge beyond the garden and the tsetse flies come swarming in along with other creepy crawlies…”

Yesterday Hr. Beck found a bedbug, she tells them, high-spirited after the flaming-hot day — “Even as we were driving up to Vesuvius yesterday there was something wrong with my insides and now I’ve diagnosed it as a slight dose of gastric flu. The kindly Danish couple who arrived recently have piled up half a medicine cupboard on my bedside table” — she predicts that tomorrow she ought to be able to launch herself at the ruins with “fresh enthusiasm.”

Fresh enthusiasm is very much the tone of the protean Tove’s early correspondence. Gastric flu and bedbugs have little chance of dampening her spirits as she zips about the Mediterranean, exploring with gleeful enthusiasm and vim.

“Of all I’ve seen, Vesuvius is certainly the highlight.” she writes. “We set off at 6 in the evening and drove up the new autostrada, which was only finished two months ago. It zigzags almost all the way up to the summit, and then you walk the rest of the way with a guide. Way down in the valley you could see the lava from the 1906 eruption towering up round burnt-out houses and, the higher you went, the wilder and gloomier everything got, the villages and Capri and the sea disappearing in the heat haze until everything was just a confusion of gravel and fabulously intertwining streams of lava, like a snakes’ wedding …”

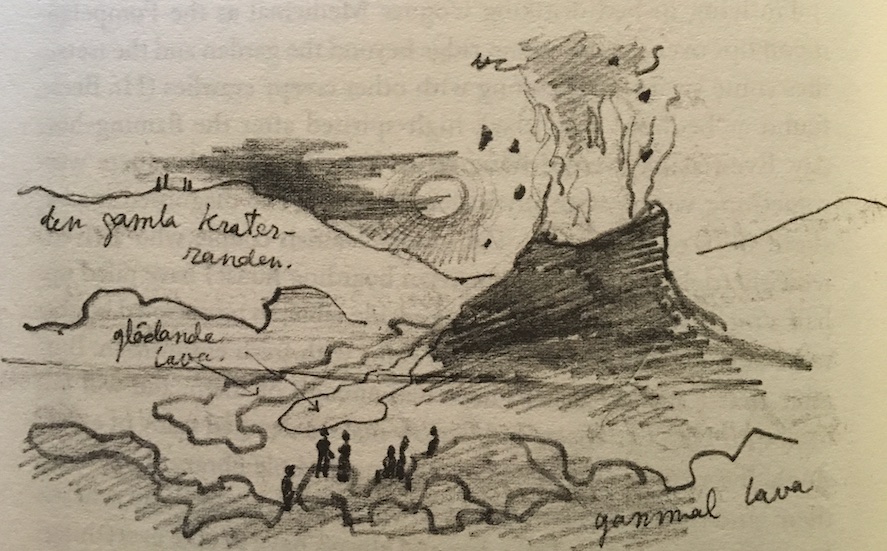

The description is accompanied by a marvellous pencil sketch. Tiny figures stand and sit before an immense mottled lava field whilst, to the right, a great black cone blasts fire and debris heavenward. A dark cloud threatens to overwhelm the hopeful sun. The hot jaspé of the foreground is annotated, each lava spill and stygian snake set down. It’s a work of tremendous energy and attention. One can imagine the artist cradling her notebook on the rim of the old crater and down into the cavity “from the centre of which Vesuvius hurled red-hot rocks high into the air, and huge plumes of fire at regular intervals” — working to record the immediate fidelity of the scene.

A version of the elemental sketch described appears in 1977’s The Dangerous Journey, a blazing mountain of the same shape circled by transfixed hattifatteners as it fires flame into the sky. The shattered pyramid cracks black and red, a crowd of onlookers stare aghast. Almost four decades after her Vesuviun encounter, Tove’s memories still shone in Technicolor.

Often in the collected letters one is aware that a double narrative is afoot, a magical mix of image and word. The bulletins are often raw in their record — actual first drafts in the case of some of the stories and images that would later recur in Tove’s published work — but they retain a gorgeous Polaroid quality read afresh now — ecstatic cinematic epistles:

“Everywhere you could see it smouldering in the cracks, yellow-green with sulphur, there was a rumble beneath your feet and it grew hotter and hotter. A little newborn crater, 4 days old, was sending out streams of lava right up to our feet, and behind it all the sun was setting amidst the brown vapour. We were allowed to light cigarettes on the lava…and we sat and looked at the splendid sight until it got dark and the whole thing looked the very picture of Dante’s inferno.”

2.

The Island (Bredskär)

June 5th, 1952

In a letter written 13 years and one day later, Tove writes to her emigre friend, photographer Eva Konikoff. The letter was written on Bredskär in the Finnish Gulf, the island Tove would later hymn and immortalise in The Summer Book.

“Dearest Eva,

…If only I could have you here for a week on the island! That’s how long I’ve been here with Ham [Tove’s mother]. When we came I was on the verge of tears from exhaustion and nerves, but now calm skies, horizons, the quiet and the gentle monotony of the days have wiped all that away. It’s strange to think there was a time when I didn’t “like nature”. How stupid.”

How can this be? What was this!? Such a sentence seems anathema to one’s image of Tove — an artist who seemed to earth her wonder at the natural world into her work, whose biophilia coloured everything she wrote and drew. “He thought about how much he loved everything;” she says of Moomintroll in Comet in Moominland (1946), “the forest and the sea, the rain and the wind, the sunshine, the grass and the moss, and how impossible it would be to live without them all, and this made him feel very, very sad.” Later, in Moominland Midwinter, when Moomin experiences snow for the first time, Tove manages to express his revelation in simple electric prose:

One by one, the snowflakes floated down on to his warm snout, and melted. He reached out to grab them so he could admire them for a fleeting moment. He looked towards the sky and watched them drift down towards him, more and more, soft and light as a feather. “So that’s how it works,” thought Moomintroll. “And I thought somehow that the snow grew from the ground up!”

To be able to conjure such a beautiful scene of joy and surprise from elements so well known, to invert the snow’s fall and renew its wonder in her readers’ minds; how could such a seer have once been blind to nature? Yet, she tells Eva, it was once so.

“… I’ve often described Bredskär to you.” she goes on. “You know everything that generally happens here, what I get up to, and that I’m happy on my island. So I’ll tell you instead what happened in town this hectic spring.” Four big paintings were accepted at a Helsinki gallery — “And better reviews than I had before the war. Maybe my painter’s block will ease off now.” And she’s been working on two big murals for the coastal town of Frederikshamn, ‘The Beach’ and ‘Seabed’ — “Working full days most of the time — and they were ready a week before I came out here for Ham’s 70th birthday, just in time…What made it such a rush was cartoon-strip business getting in the way, a chance that I didn’t dare pass up. Mr Sutton [Tove’s Moomin agent in London] came over on the last day of April to agree a contract between Associated Newspapers Ltd and me, and I had to have synopses for 80 cartoon strips ready for him.

I finished them the day he came. In the evening a big May Day Eve party for him at the studio for 20 people, guitars and Finnish brandy, irate caretaker, balloons, intrigues, dancing and morning coffee, the whole works…Mr. Sutton may have got a somewhat misleading impression of Finnish high spirits, but he certainly enjoyed himself.”

Meanwhile, a British translation of Moominpappa’s Memoirs is underway, and a Swiss publisher is interested in Finn Family Moomintroll; the Moomin, Mymble and Little My picture book is now at the printer’s and has also been translated into Finnish, and she needs to build stage sets for the Finnish Ballet in time for summer…

“I’m firing off commercial letters in all directions and am amazed at the sheer volume of all the Moomin business,” she tells her friend, and it’s an amazing thing to read her on the cusp of global fame; unsure where “the Moomin business” might be headed but determined to give it a go.

“If the cartoons prove popular in London I shall be engaged for maybe 4 years to deliver one a day. Permanent employment — the first time in my life…They want them quite large with lots of detail and keep changing things and raising objections, so it takes quite a long time to finish a whole strip. Here on the island I’ve finally had time to make a start on them — I’ve got to deliver them regularly, in bundles of six.

Where to put in murals and oil painting…?”

Where indeed!?

Tove was about to become busier than she could ever have imagined.

3.

Letter to Tuulikki Pietilä

Bredskär

4th May, 1962

Ten years later, Tove is again on Bredskär, alone but for her cat, Psipsu, but much has changed.

First, I note with delight that Tove is writing to Tuulikki Pietilä, who she met in 1956 and would go on to become her life partner. Tuulikki, known as Tooti — the inspiration for the character “Tooticki” in the Moomin books — was a remarkable graphic artist and printer, who taught for many years at Helsinki’s Academy of Arts, and was to be Tove’s great love, rock and creative foil ever after.

For Bredskär, the news was less good. In October 1961, the Swedish cargo vessel Coolaroo sank in the Gulf of Finland, leaking a large amount of oil in the process:

“And here it just keeps raining and blowing a gale, so I’ve started painting. As soon as it brightens up even slightly we’re out like a shot, Psipsu and I, burning stuff from the wreck and other rubbish caught in clefts in the rock, salvaging seaweed, chopping wood…and then the Weather sweeps in again from some angry direction and drives us indoors. It’s at its most vicious now, from the north, and the whole island is a palette of wet, earthy colours, with splashes of white snow and black oil.”

At the northern point of a neighbouring isle, oil has formed in huge pools, she goes on, along with great piles of grot-slicked driftwood. She tried to tidy things up, “made a few minimal heaps” of detritus but the scene she paints is one of dismal mullock. However, as ever with Tove, there are silver linings yet; “I found pussy willow and alder catkins and the birds were singing like crazy in the branches” she signs off, wishing Tooti were there to further brighten her world.

A couple of years after this last letter was written, Tove and Tooti moved out from green Bredskär to the black whale-back-like islet of Klovharun (as recorded in a letter and sketch of 10th June, 1964). Tove’s fame had brought with it a steady stream of friends and interlopers to Bredskär, with the result that the peace and quiet were often interrupted.

On my visit to Pellinge, I met Kim Gustafsson, with whose grandparents Tove first stayed when she visited the archipelago as a child. Kim showed me an attic room where Tove wrote Moominvalley in November, sitting at little desk throughout the winter of 1970. He opens a window and points out the roof where Tove practised sliding “as research for the book” and tells me how his bewildered family sat listening in the kitchen below, wondering what on earth she was doing. And he showed me a poster she made in light of the Coolaroo disaster; a seascape with a lighthouse and a black trail of oil which swirls to the front of the frame, where Snorkmaiden sits in a little boat, brow furrowed, ladling the sticky dreck into a pot. The caption, Kim told me, reads: “Keep the Sea Clean.”

When I got back home I asked my mother why there were no Moomin books in the house growing up, and she replied that they always seemed “too dark”. Reading them back now, I see that darkness as a subtle thread which runs through all of Jansson’s work. The summer days may be bright, but the winter nights are long and deathly cold. Yet there is always hope in the darkness, and, if Tove’s collected letters allow us a window into her world, they also reveal a great legacy of environmentalism, love, and positivity — a campaigning desire to protect and cherish the planet, to leave no trace, to do no harm.

Hopefully Overnight will carry some of the same fire.

*

With many thanks to Sort of Books for permission to quote from Tove’s letters, and to Moomin Characters for allowing us use of Tove’s original artwork and photographs.

‘Letters from Tove’, published in paperback by Sort of Books, is out now. Buy a copy here or from your local independent bookshop. Alternatively, chance your arm in a Caught by the River newsletter competition in the coming weeks, when we’ll have 3 copies of the book to give away.

Dan Richards’ latest book, ‘Outpost: A Journey to the Wild Ends of the Earth’ is out now in paperback.