Mandy Haggith’s ‘The Lost Elms’, published earlier this month by Wildfire, defies us not to fall in love with elm trees, writes Kirsteen Bell.

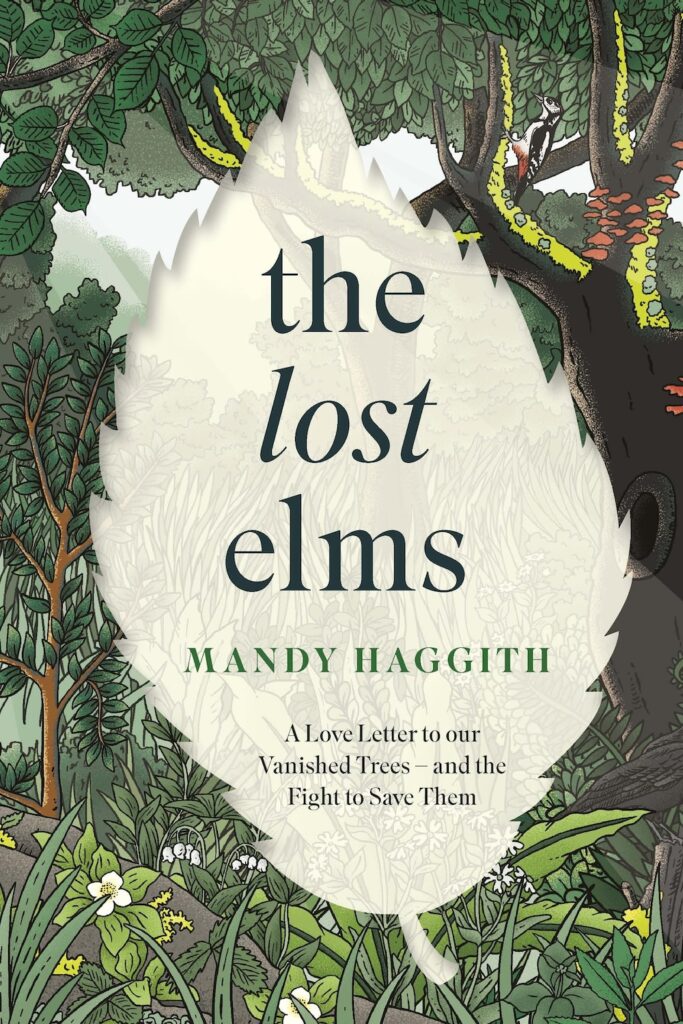

You could not write a book about elms now without first addressing the threat to their existence. The ghostly imprint of a leaf on the cover of The Lost Elms, over an otherwise abundant wood, gives some indication of Mandy Haggith’s intention to face the devastation of Dutch Elm Disease from the outset. DED decimated Haggith’s own childhood trees, so she has long known its ability to wipe out entire woods. Rather than despairing in the loss however, Haggith flips it, again and again, death and life on repeat, as she roots into the ecological and cultural history and life of the elm, and all that is being done to save it.

Haggith lives on a croft in Assynt with her husband, in what she calls a ‘zone of hope’. The bark beetles (Scolytus scolytus) that carry DED fungus are held back by colder climates, such as we generally have in the North of Scotland. Assynt lies just beyond the beetle’s range.

I visited that croft towards the end of last year to meet some of the trees in Mandy and Bill’s woodland. I did not meet an elm, but I did meet a regal stand of aspen. At the time, I told Mandy that we had no aspen on our own croft, and certainly no elms. Cut to a few weeks later and I stumbled upon the sawn log of a single aspen, left from contractors’ work on a neighbouring croft. We had had an aspen – and it was gone before I had even known it existed. Remembering that moment as I was reading The Lost Elms, I began to look for rogue elms in my daily travels up and down the lochside. I have yet to find one.

Haggith, however, has uncovered elms in every nook and cranny of the world. As she goes beyond the disease to look at elms’ practical and medicinal uses, their folklore and legacies, she shares the lives of multiple elm species and genera across the globe. It is eye-opening and heartening, to say the least. I particularly like her refusal to bow to the many taxonomic changes that elms have been subject to. No matter how tenuous the link to the elm family in the eyes of botanists now, all are welcome in this encompassing celebration of these trees. Just as she describes the local elms known from her walks into the Assynt woods and hills, it is as though Haggith has walked the world over peering in every gully and glen for any elms she could find. And whether we are taken to Europe, America, Africa, Australia, or Aotearoa, each story is told with a sensitivity towards the many ways humans interpret and relate to the trees.

Her own presence in the book is a steady guiding hand, in the same way that elms have been for her, and her research is full of the warmth of feeling she evidently has for them. Trees have been an integral part of her life and identity from a young age. Across the book, the death of the elms is lightly linked to the death of her parents. While there is a clear sense that it is a comparable grief, this is not a book that touts nature as a cure for human ills. It is that these trees are of comparable and fundamental importance to all our lives. The climate grief that permeates much of our days is immensely relatable in Haggith’s own experience of living through personal and environmental grief. By focusing on the elms, she shows that embracing grief is vital to caring enough to fight.

Knowing the depth at which elms have been present in culture and folklore across the world does make their absence harder to bear. In the chapter on Elms in the Arts, the fading of elms from contemporary poetry is as much a concern as the loss of the trees themselves. How can we fight for something if we have forgotten it? This absence in our minds perpetuates the idea that elms are utterly and irrevocably lost, that there is nothing to be done. The truth, as Haggith shows, is much more hopeful.

As a poet and writer, she argues for the power of the arts as a means by which we can see beyond the scope of our own small lifespans and into the lifespan of species such as the elm. Literature, music, visual arts all provide an expansion of view that is necessary for humans to see our way out of climate grief and into positive action. This is what makes The Lost Elms so important. Like the Japanese nagado drum made from a type of elmwood, that holds ‘the spirit of the tree its body came from’, Haggith’s words are embedded with the spirit of elms. As a result, you are left feeling like one of the more resilient species, ‘botanically and culturally rooted.’

This book defies us not to fall in love with elm trees, with the idea of elms and all that their loss and what remains represents to us. Younger generations of readers, who might not know what they are so very close to losing, will know the tree more intimately. Those who remember elms as a prolific presence in the landscape will find recognition, and a quiet promise to fight.

My thoughts turn again to finding a living elm near to me. I message an arborist friend to ask if he knows of any growing locally. He replies simply with a photo of a gorgeous leafy tree from his own garden. Its thick trunk is rich with moss, and its crown of many branches is full and resplendent in the sun.

*

‘The Lost Elms: A Love Letter to Our Vanished Trees – and the Fight to Save Them’ by Mandy Haggith is out now and available here (£20.90).

Kirsteen Bell lives and writes on a croft in Lochaber. She can also be found at Moniack Mhor, Scotland’s Creative Writing Centre, where she is Projects Manager and Highland Book Prize Co-ordinator. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter.