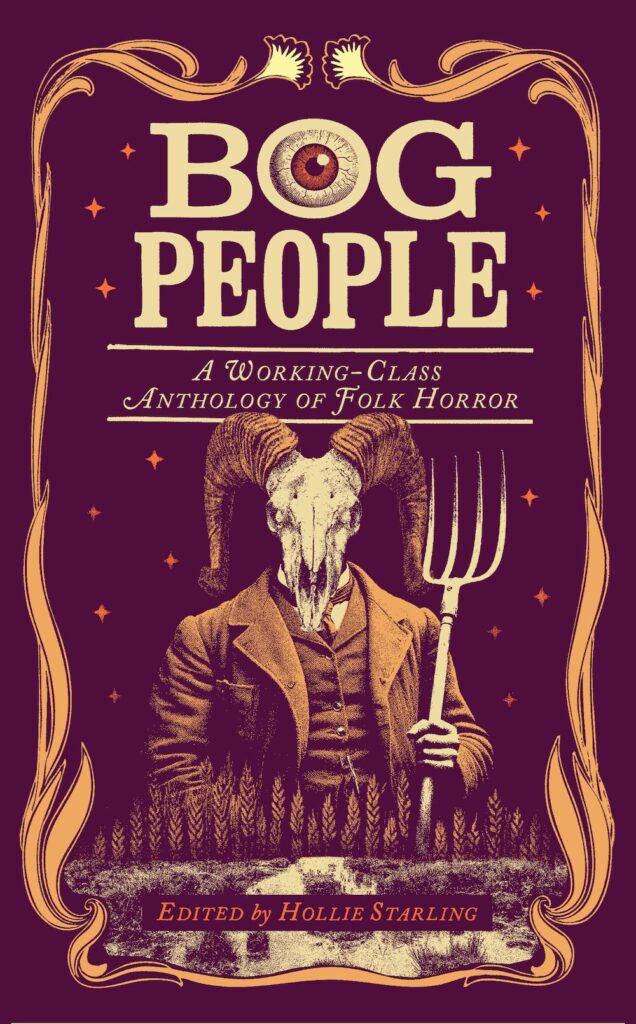

October Book of the Month is ‘Bog People: A Working-Class Anthology of Folk Horror’. In the following extract, a condensed excerpt from the introduction, anthology editor Hollie Starling considers the disruptive potential of stories to upend fortresses of power.

Once a year, the market town of Honiton in Devon performs the rites of a tradition thought to be more than 800 years old. Children gather in the town’s public square to compete for pennies cast out from the windows above. In times past, the nobility found it amusing to watch peasants scrabbling in the dirt for the coins. Back then, it is said, the pennies were first heated on the stove. Why? Because the spectacle was much more entertaining, the desperation much more evident, when to collect them the poor had to burn their fingers.

There is power in tradition. ‘The way things have always been done’ carries an authority that resists scrutiny. A self- styled mouthpiece of a community’s ancestors can be particularly persuasive. Take Christopher Lee’s betweeded autocrat Lord Summerisle in the 1973 film The Wicker Man, speaking of his father and father’s father before him: ‘He brought me up the same way, to reverence the music and the drama and the rituals of the Old Gods. To love nature and to fear it. And to rely on it and to appease it where necessary.’ His unique ability to interpret and placate this power allows Summerisle to control and guard the purity of his island. It is a trick of rhetoric not limited to fiction. In a memorial speech for St George’s Day 1961, another charismatic orator invoked ‘our ancestors’ directly, imploring them to ‘tell us what it is that binds us together; show us the clue that leads through a thousand years; whisper to us the secret of this charmed life of England, that we in our time may know how to hold it fast’. Some years later this man, Enoch Powell, would deliver his inflammatory ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, carving a discursive cleft through class and identity with which modern Britain still wrestles today. Being long dead, it seems, is of no consequence; our ancestors can be summoned to aid and abet just about any agenda, especially when a touch of romantic nationalism may help to grease the wheels.

This is, I think, what thrills me about the genre that began in Britain but has become known worldwide as ‘folk horror’. The menace feels so acute because real monsters do tread this green and pleasant land. It is a genre of obsession, and in that way mirrors Britain’s perpetual fascination with itself. Dual preoccupations – a mythic Albion of spellbinding legends and glorious sovereignty, and deeply embedded systems of class and rule – mould and inform, in a Powellian echo, ‘what it means to be British’. In folk horror the soil beneath our feet is seismically unstable. Our closest kin are unknowable and depraved, bound by unseen influences. As folk horror often examines belief, the very keystone of our identities, the moral peril is genuine. That we may be bewitched by the stirring words of a convincing populist, or fall into mass psychogenic hysteria, or take for granted ancient narratives of which we have little understanding, keeps us on our toes. Nothing can be relied upon.

Storytelling has always been one of our favourite pastimes and Britain’s bursting catalogue of folklore has provided plenty of grist for the mill. It might be said that folklore, as distinct from recorded history, is a type of collective social memory. Memory, subject to glitches and distortion, is naturally imperfect; but its capacity to capture experience and emotion offers its own sort of truth. A shared repository of familiar archetypes and narratives fosters a sense of community and belonging. Stories may become amulets for regional groups and, over time, the ingredients of national identity.

Unfortunately, tradition has been invoked to defend all sorts of cynical examples of British ‘cultural heritage’, from fox-hunting to blackface to smacking your kids. In online spaces, folk imagery, wistfulness for unspoilt landscape and appeals to ‘indigenous’ pride are used as dog-whistles to further the ethnonationalist fantasies of the far right. So it is essential that we define what folk horror is, and what it is not.

***

The great unwashed has always been an inconvenience, the grubby workers’ hands on the wheels of commerce an understood necessity, though an unsightly one. Those vested in the maintenance of capital-driven systems of control have worked hard to distract from one of history’s most abiding truths: that there are more of us than them. So often in folk horror narratives we see a culmination of an aberrant individual or group suppressed by the multitude. In this moment it is the perfect genre to glimpse an exhilarating role reversal, to provoke a change of regime. To conjure together a Feast of Fools that endures beyond dawn.

With Bog People we excavate the mud-bound relics and restore the great unwashed. In its pages we recognise the countless dead unnamed by the chroniclers of history; the poor, but also women, people of colour, marginal identities, the voices of the colonised, silent and suppressed. Together we will relearn the disruptive potential of stories to upend fortresses of power. Stories of reaping and sowing, stories that turn the staid soil so something fresh can grow from it, stories as sharp as a guillotine blade, stories to persist for all time.

Hollie Starling London, May Day 2025

*

‘Bog People: A Working-Class Anthology of Folk Horror’ is out now and available here (£18.04), published by Chatto & Windus.

Author and editor Hollie Starling grew up in north Lincolnshire and now lives and work in London. She runs the page Folk Horror Magpie on social media.

A bonus interview with Hollie, delving deeper into ‘Bog People’, working class representation and the wider Folk Horror genre, will be going out to paid Steady subscribers before the end of the month. Take out a paid subscription here to have it delivered to your inbox, and to gain access to last month’s bonus interview with Nicola Chester.