Dexter Petley reflects on the year his field became a forest.

Put simply, 2025 has been the year during which my field became a forest. Hec est finalis Concordia.

This new forest is not on parchment or in the feet of fines. It is not a forest because of the trees. Arboriculturists, I should add for veracity, might argue the terms and stages of succession, that it is only a forest at the first tree felled. Purchased as naked agricultural flood pasture in 2010, its one dead ash stump sat in bramble fester, seven oaks lined the lane, a straggle of goat willow and hazel shoots sporadic along the nettle boundary, an aquifer one yard underground, according to the water diviner. Not a lot to go on, though homeward bound. It even had a topographical name from 1077, La Folie, feulliée, fullie, foille, folie, a shelter of leaves.

Technically cued to become an ecotone, I dislike the term, my palimpsest was nonetheless a transitional zone between two different habitats. The idea was for the eventual presence of both species and features from bordering habitats. Though triangular, I counted four; two forest, one pasture, one tillage.

From the beginning, it was out of my hands. By its second summer the farmer said it was too woody to cut for hay. Pioneer saplings were arriving from the mother forest either side. At one end, the potager struggled then sank in soaked clay and marsh grass. At the other I hoisted camo nets to conceal my illegal home from any passing collaborator. La Folie, also a cabane, or maison de campagne. I need not have worried. Today, even the Google plane cannot spot the yurt.

My first autumn act of 2010 was to plant a twenty-six-tree orchard of mixed fruit. Each tree hole filled with brown water as I dug them, months after the first garden crops had already rotted in the ground. La Folie, according to Le Robert, dictionnaire historique de la langue française, poor ground only a madman would cultivate. For years the saplings stunted at competition level, the campagnoles and musaraignes stripped their bark until, when finally they struggled into flower one spring, they’d reverted to their root stocks, mostly gender-neutral prunes. Good cherry, pears and apples, plums and greengages floundering in no mans land.

In the intervening years, the jays chipped in to save the day. By their raucous meanderings, bombing acorns hither and thither, the one-by-one became thousands. Stubby oaks rose above the height of rye grass and marsh thistle. The winds supplied the rest. Aspens and ash, hazel and willow, beach, hornbeam and gean, all spreading in moonlight, until this year the fruit trees, deciduous and mycelium became one place, habitat united, 3-in-1, a forest garden as I sat and watched. Neither Weald nor Anderida of my roots, just the coincidence of joined hands, my triangular hectare and a spit is now the meeting place for the offspring of old forest pushed in from either side. Naturally aspirated, seen from the air or the ground, a young forest not because of trees, which do not on their own make a forest, but because of the mushrooms.

This summer, they came, these mycological migrants, in their thousands, in rings and rows, ranks and in reams. At first, they seemed to map the animal passages, having come by hoof and claw from three sides, few edible species yet, just their harbingers and precursors, the edibles spored-in for the next rise, or the next. The mousseron, though technically a field species, showed up in both spring and autumn variant. Both were eaten to ritual, as blood-of-ground in a kind of coming-of-age omelette. And among the aspens, now trembling with anticipation, the true heralds of boletus, the fly agarics, up and at ‘em, leaving their message poste restante. Cortinaires and pholiotes, lactaires and hygrophores, the latter at the first frosts, edible if mediocre. The fruit trees shared the evolution of good news. Dishevelled and unpruned, they flashed a show of April blossom which could only mean trouble come harvest. The orchard, having decided to fruit after 15 sterile autumns, was invisible once the blossom died, oaked-in and brambled over. Having witnessed this march of mushrooms and the blossom revival, I cleared a passage for the miracle as best I could. Though genus unconfirmed, they poured their summer hearts out into multi-coloured balls which bent the branches and filled the baskets.

Plums of a kind, mirabelles and greengages, apples and pears, wasps, hornets and pine martens in contention for the final. We picked and bottled and jarred, stuffed, swatted, spat and composted, like spenders at a jackpot. The hornets, sensing an end to famine, stayed until the end, making caves of the late Calvilles still on the tree, relinquished only at the first November frosts.

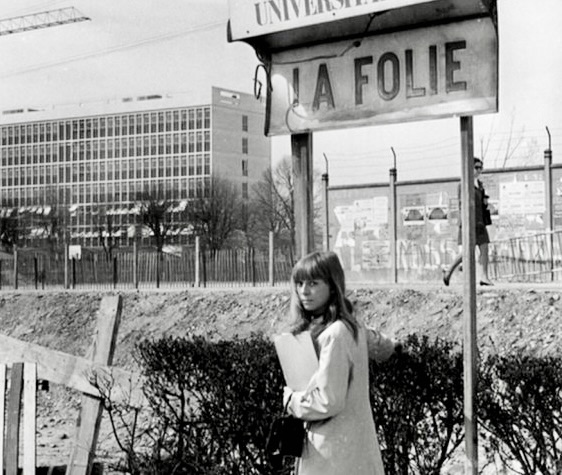

In these frosts I linger still, reluctant to pack down the outside kitchen, beside which hangs an old, enamelled metal sign with red lettering, LA FOLIE, once the name-plaque on a railway station platform. Somehow, through that mysterious passage of hands, it came to me this year, La Folie, an extravagant or dispendieuse construction. This modest sign, from the factory of Laborde, est.1900, merits personification for its place of witness, the times it saw, and those who saw it. Indeed, what’s in a name? La Folie, a stone’s throw from the Seine, was in 1690 a rich maison de plaisance, with all it implies, of boudoirs and alcoves and demi-mondaines. Underground, great caverns were created from mining the stone which built half of Paris. In 1809, La Folie became a factory producing chemicals. In 1837, a railway halt on the first line out of Paris. In 1900 the caves were rented to a champignonniste who produced the famous mushroom of Paris. An early camp d’aviation, La Folie in 1916 became a vital base where biplanes were stocked and repaired. In the Second World War the Camp de La Folie became Beutepark Luftwaffe n° 5 Nanterre, storage depot for Luftwaffe wrecks arriving by train, spare parts workshop, a black museum for shot-down allied planes dismantled for scrutiny in the laboratory of war. Swords into ploughshares, my enamelled plaque was still there on the post-war aero club platform when they built the University of Nanterre beside it. Perhaps torn down by students in the riots of 1968, La Folie being the very place where that whole thing began, or sold to a collector in 1972 when the station was rebuilt. In 2025, this old sign has been restored to camp, and the folly, also the madness, has been vindicated.

As daylight shrinks and the sun barely skirts the ground, the solar holds by touch and go, by twists and turns. Electricity is rationed to an hour per day, the power station tops the vital services, charging the fridge battery or laptop, bread dough mixer or electric bike, depending upon the weather or the task at hand. My old carp fishing barrow has converted to a mobile station, solar panel, battery and invertor, a constant standby which I wheel around the forest field as the sun pokes feebly into clearings, mostly just to keep a lamp lit above the stove. In August, the 1000 litre rain tank filled to its brim, now shut off and sealed with clean water, enough at 5 litres per week, my average total consumption, to last till doomsday. Coffee water comes from a spring in a nearby forest, the Fountain of Madame Jeanne, born 1378, daughter of Pierre II, the Comte d’Alençon. The spring was discovered by local monks in 1170 and reputed for its therapeutic properties. My old neighbour’s father, a farmer, would cycle to the fountain every morning during the war to fill the baby’s feeding bottles. Now just a bramble covered path, a plastic pipe sticks from a bank as water gushes into a gravel pool lined in brick, its 1880s thatched shelter a fenced off ruin, the thatch strewn in rough hanks along the path.

The point, it seems, of 2025, has been to complete that vision I had thirty years ago, of how life could be lived, by rain, and sun, and wood, by joined up history, wits and luck, risk and caution, sacrifice, even piety in the brunt of natural calamity, simplicity the overwhelming bounty, for in truth it’s also been about how to live on a third of the minimum wage, the neglected writer’s annuity, how nature pays your rent, fills your kettle, heats your free water. Poverty at its best, the woodshed full of logs from La Folie, the caravan-cum-pantry stocked with canning jars of La Folie, its cèpes and trompettes, green beans and born-again fruit. The palimpsest becomes botanical and bestiary, that old tin sign now turned the other way, from looking on at violence to face the sagacity of trees.