Many thanks to Neil Sentance for bringing this wonderful piece of writing to our attention. We’ll be running The Last Blacksmith in four parts: this is the first.

Part 1: Looking Back

Words and pictures: Ron Hewit

The double doors to the smithy bear the marks of the passing years. Hundreds of nails hammered deep into the wood, four horseshoes (two of them pointing up in the traditional way for luck; two pointing down), a small metal lion’s head of all things, a formidable hasp and a sneck, or latch, that feels comfortable to the touch, the mechanism worn loose and the metal thin by a million hands and fingers or, more likely, the same few fingers and thumbs a million times over. That reassuring dragging click of metal kissing metal.

The doors are a shabby mustard colour, worn dull by time and neglect, but on the left-hand door at shoulder height there are ten small circles of paint, the fading legacy of my boyhood Airfix habit. I would daub some Humbrol paint on the plane or ship I was making, walk out to the smithy, pausing to wipe excess paint off the brush on to the door, creating a crude circle of red or green or blue, pour a trickle of petrol into one of my dad’s empty tobacco tins, clean the brush, then wipe the excess petrol off the brush on to the door on the way back to the house. My dad wasn’t best pleased when he saw what I’d done. Now he’s dead, but the blobs of paint remain and will still be there when I die.

The sneck on the smithy door, 2015

The sneck on the smithy door, 2015

Nothing happens in Heiton. It’s a blink and you’ll miss it village, a straggle of houses either side of the main road between Kelso and Jedburgh in Roxburghshire in the Scottish borders – farming country. At one time, the village had a pub with stables and a school but now the pub has gone, the school is a private house and the stables were long ago turned into the village hall. The smithy house was built in 1849 and was originally a one-storey dwelling before it acquired a second floor in the early part of the 20th century. Built from local sandstone, it’s nicely proportioned and looks over an upward curve of fields, trees and hedgerows to Bowmont Forest on the crest of a hill.

To the rear, fields lead down to the River Teviot and hunched on the horizon are the three distinctive mounds of the Eildon Hills. The house and smithy are made from the same stone and are interlocked, forming an L-shape. They seem fused together, deeply rooted and permanent. The house next door was owned by the Dodds family, the wheelwright and joiner, their home and workshop a mirror image of ours forming a similar L-shape. For generations the Doddses would make the cartwheels and the Hewits, the blacksmiths, would fit the iron rims, the two businesses and families, like the two houses and their workplaces, intertwined.

My dad, Bob Hewit, was born in the smithy house on 29 January 1928. He grew up there and worked in the smithy as a blacksmith and master farrier for more than 50 years, learning the trade from his father as he had learnt it from his. Dad moved a hundred yards up the village to a council house after he married my mum, Wilma, in 1958; they had my brother John and sister Sandra and then moved back to the smithy house in December 1962 when his parents moved to a bungalow they built two doors away on land where once Dad had led the family’s cow to graze each day.

I was born on 27 January 1963, the fifth generation of Hewits to be born above the shop. When my granny died in 1987 my parents moved into the bungalow and my brother John and his family moved into the smithy house. Generation following generation, another slow roll of time, but by then I’d left Heiton behind for student life in Edinburgh.

I’ve been back home many times since then, but no return journey is more poignant than this, just days after my dad died peacefully in his own bed, in the same room in the bungalow that his father passed away 40-odd years ago. This time I’m drawn back to the smithy in search of memories and connections.

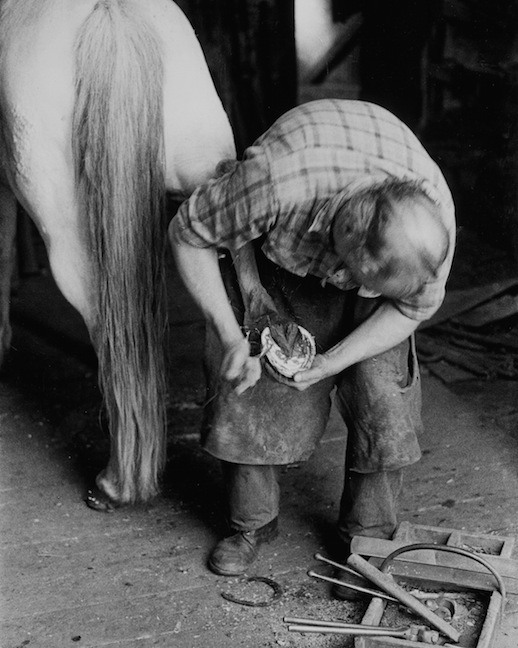

The double doors were only fully opened when a horse came to be shoed. The kitchen window looked out to the area in front of the smithy doors and I remember, as a child, hearing the clatter of hooves on a Saturday morning and rushing to the window where the view would be suddenly filled by a huge, snorting horse, the frame allowing only a close-up of its shoulder, flank and belly, the rider’s leg and the stirrup. My dad would be waiting, leather apron on, the smithy floor already splashed with water and swept “to keep the stoor doon”, the coals in the forge fired up and red-hot, ready.

Shoeing a horse is a highly skilled job – removing the old shoe and trimming the hard hoof wall with a set of nippers; clearing out the dirt and debris from around the softer sole and frog of the foot and carefully trimming them with a sharp, curved knife; filing the foot flat with a rasp then placing the new shoe so it fits perfectly before finally driving the nails home. It’s also back-breaking – you’re bent almost double, taking the weight of the horse’s hoof either between or on your knees.

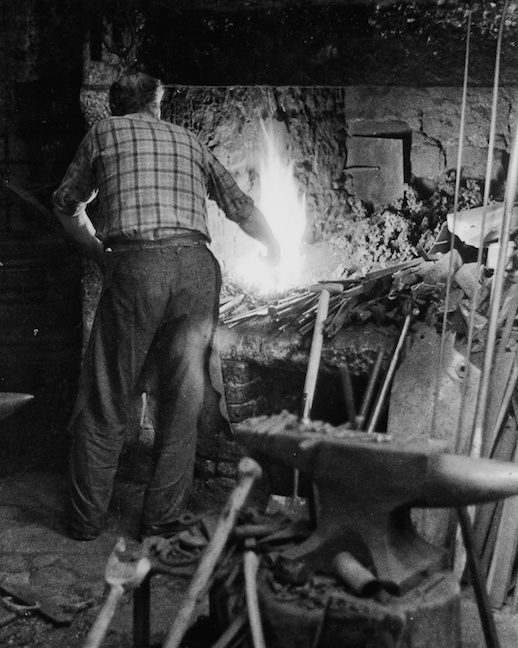

You could buy ready-made horseshoes, but Dad would make each set of shoes from scratch from a bar of steel. He knew the measurements of every horse he shoed regularly and would produce a copy from a master set every time new shoes were needed. Whenever a new horse needed shoeing he’d carefully measure its hooves a few days before it was due at the smithy to give him time to make the shoes. He preferred hot shoeing – heating the shoe

in the forge until it was hot enough to make a mark on the trimmed hoof, which allowed him to check how well it was fitting, making small adjustments at the anvil as he went. The smell of a hot shoe on a horse’s hoof is one you never forget. It’s a dramatic sight, too, with smoke billowing from the hoof and a dense, acrid smell similar to burning toenails but more intense. As a finishing touch Dad would give each hoof a quick rub with an oily rag to make it shine.

Dad shoeing a horse, circa 1980s

Dad shoeing a horse, circa 1980s

The area outside the smithy is nondescript but rich in memories. It’s where the rims would be fitted on to cart wheels, an operation I never saw but which Dad described to me – clouds of steam rising as the hot metal was cooled rapidly, the cracking and groaning of the wooden spokes as they were forced tighter into the hub by the contracting metal. One of my favourite family pictures shows my grandad, John Hewit, standing in the same area. It’s difficult to tell when the photograph was taken, but it’s probably the mid-1920s. In it my grandad is standing next to some unfathomable piece of machinery that he’s working on, a pair of pincers in one oil-blackened hand, his grubby collarless shirt buttoned to the throat, the sleeves rolled up above the elbow, leather apron around his waist. He looks long-limbed and relaxed, eyeing the camera with an easy confidence. Behind him the smithy doors are open, the interior tantalisingly in shadow, the outer wall and window almost the same then as they are now.

Grandad, John Hewit, outside the smithy, circa 1920s

Grandad, John Hewit, outside the smithy, circa 1920s

The doors have stood for decades unnoticed and unchanged apart from the rectangular notch cut into the top of one door, my dad’s thoughtful contribution to swallow husbandry. It meant the door could be shut and locked when not in use, but allowed the swallows that arrived each summer to take up residence to come and go. For a man who never travelled further from home than Jersey, Dad had a touching affinity with and love for the swallows that flew thousands of miles from their winter quarters in Africa to breed in the smithy, an annual miracle of nature and navigation, generation after generation flickering and darting through its doors. Come the early days of May he’d be on standby waiting for the first one to arrive, never happier than when his swallows had returned safely to their old nests or made new ones among the struts high in the roof. Later, the ranks of young swallows lined up on telephone wires, chattering and fidgeting, wings itching to begin the great migration back to Africa, were a sure sign that autumn was nearing.

My brother John has also made his mark on the doors – swipes of white, red and black paint showing that the habit of cleaning paintbrushes on doors runs in the genes. I could stretch now for a phrase or a sentence to knit these memories and images together and come up with something trite that would give shape and meaning to it all. But my dad would have scoffed at that. Where I peer through memories buffed golden by the passing years and see links and loops threaded through time he, unfussy and practical, would have said it’s all just people and time doing what they do.