brought to us as always by Mr Andy Childs.

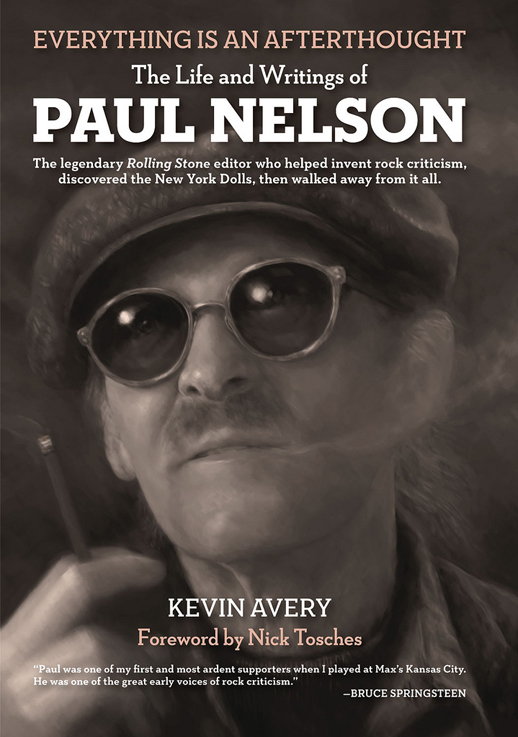

Everything Is An Afterthought : The Life and Writings of Paul Nelson

by Kevin Avery

Fantagraphics Books 497pp hdbk.

When I first started to have enough money to buy records on a regular basis my guide to what I should be listening to was largely the Rolling Stone record review section and its staff of writers whose taste and judgement I learned to trust and respect. Most of the time anyway. Greil Marcus, Lester Bangs, Ed Ward, John Mendelsohn, Jon Landau, Peter Guralnick, Lenny Kaye – these are all writers whose names and reputations have for one reason or another endured. And then there’s Paul Nelson, up there with the best of them but tragically forgotten and as a result cruelly under-rated.

Reading Kevin Avery’s meticulous and affectionate biography of Nelson, which comprises half of this book, it becomes apparent that when the history of rock’n’roll is ever written as it should be then he, Nelson, will take his place as a pivotal and hugely influential figure. Here are a few reasons why :

Born in 1936 in Minnesota into a religious household devoid of culture, Paul Nelson’s first love was folk music, which he shared with life-long friend Jon Pankake whom he met at the University of Minneapolis in 1957. Their other folk buddy at the time was Bob Zimmerman to whom they introduced the music of Woody Guthrie and Jack Elliott. His Bobness actually stole about twenty or thirty records from Pankake in order to enrich his repertoire. So Paul Nelson pointed Bob Dylan in the direction that would re-shape the whole landscape of popular music.

Then Paul and Jon, inspired by Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, started a folk music magazine, perhaps even the first music fanzine, called The Little Sandy Review which ran for thirty issues until 1963 and in that time informed and prompted a generation of musicians to go on and create the ‘new folk scene’. It counted Barret Hansen (later to be known as Dr.Demento) and Tony Glover among its contributors and via his connection with Jac Holzman managed to get the great Koerner, Ray & Glover signed to Elektra Records, and even produced their first album.

After graduating from the University of Minnesota he moved to New York and in 1964 became the managing editor – some say the best-ever – of the other eminent folk publication, Sing Out!, and began to develop a style of writing that was more introspective and personal, but nevertheless passionate and fully engaged, and I don’t think it’s too fanciful to suggest that he influenced the other great pioneer of serious music journalism, Paul Williams (founder of Crawdaddy magazine). Nelson’s style was also adopted and developed later by the likes of Tom Wolfe and other lesser writers eager to embrace the ‘New Journalism’ as it was called. Paul Nelson was first though.

The Newport Folk Festival of 1965 changed Nelson’s life as it did for most people who were caught in the cultural tsunami of Dylan’s electrified performance. Having simultaneously witnessed the future of folk and rock music and unable to continue to commit himself to a ‘traditional’ folk mag he immediately resigned as editor of Sing Out. He did freelance writing for a while and became Rolling Stone’s first New York-based writer – not an especially fruitful episode as he left after penning just ten articles and then, surprisingly, went to work for Mercury Records in 1970, first as a publicist and then as an A&R man. In the latter role he went head-to-head with the prevailing culture of complete antipathy towards anything other than MOR that existed at Mercury at the time and his reminiscences of meetings and discussions he had with bewildered, hapless execs are very funny and totally believable. In an episode that reminded me of nothing so much as the clueless CIA personnel in the film Burn After Reading he somehow persuaded the top brass that it would be a good idea to sign Mike Seeger for two albums, Music From True Vine and The Second Farewell Reunion , and even though his boss kept referring to them as Deep Purple he managed to persuade him to cough up a bargain $20,000 for The Velvet Underground 1969 Live album. But his greatest claim to A&R fame, and the deed that eventually led to his downfall at Mercury, was the signing of The New York Dolls, which, given his background and circumstances was a remarkably brave thing to do. This whole period in his life is encapsulated in the book’s most entertaining chapter, titled ‘Looking Back’, where Nelson reveals a rarely-displayed but brilliant sense of comic narrative analyzing his tenure at Mercury and the stultifying amount of ignorance and corporate stupidity he had to endure. He tells of a ‘big name manager’ scam that is outrageous and hilarious in its combination of audacity and naivity and his artist-related episodes are equally amusing – great Jerry Lee Lewis and Doug Sahm stories and the barely credible tale of how he had to tactfully inform David Bowie that the Lou Reed he thought he’d been introduced to by Nelson was in fact Doug Yule. Such anecdotes are trivial to be sure when stood up against the serious business of rock criticism but they provide some light relief near the end of a story that portrays a life and talent so rich in promise but that eventually ends up in semi-obscurity and destitution.

When his presence at Mercury eventually became more than he or they could bear he went freelance again for a while and then re-joined Rolling Stone as record reviews editor. But his relationship with founder Jan Wenner was a stormy one and he quit again (his letter of resignation, re-printed in the book, is a work of art in itself) when Wenner introduced the ‘star system’ for record reviews. As Dave Marsh commented : “That was the death of rock criticism right there”. And long-form rock criticism was Nelson’s forte and a craft he took very seriously.

His dedication to grasping the core of an artists’ music and trying to explain what he found there sometimes took him to the very edge of pretension but he was a totally implacable writer unafraid to dent the largest of egos in his rigorous adherence to the probity of his craft. The second half of this book is devoted to distinguished examples of Nelson’s writing. Bob Dylan, Elliott Murphy, Leonard Cohen, Patti Smith, Jackson Browne, Rod Stewart, Bruce Springsteen, Neil Young, Warren Zevon and The New York Dolls are all artists he interviewed, wrote extensively about and in some cases became close friends with, although, true as ever to his ideals, he never let friendship get in the way of his critical integrity. And I guess that’s one of the things that makes Nelson so special. In a business that accepts compromise, double-standards and moral cowardice as the norm, Nelson refused to be diverted from the purity of his writing. His intense submersion in his subject matter, the intellect he brought to the critical process, the agonised consideration he gave to every piece he wrote and the passion with which he expressed himself made him a great rock critic. It also probably made him unpopular with some people and almost certainly made him ill-equipped to survive in the music business.

When he left Rolling Stone Nelson retreated from the wider world and his professional career and private life went into gradual decline. He was undoubtedly a troubled man, plagued by insecurity and doubt. With a failed marriage behind him and seemingly never willing or able to maintain a long-term relationship he fell in and out of love with a variety of women. A marathon runner and smoker, his personal habits were singular – his Rolling Stone author biography stated that “among New York literati Paul Nelson is known for drinking two cokes with every meal and not eating a single green vegetable since Dylan went electric”, and there was an intensity and a degree of eccentricity in his general behaviour that seemed to make socializing difficult for him. Surprisingly for someone whose life was inextricably bound up in music and the music business, Nelson’s first love was actually film, a subject on which he was an authority and an occasional writer. At one point he was going to start a film magazine, financed by Jac Holzman, but like too many of Nelson’s great ideas it came to nothing. Through a combination of adherence to his own exacting standards and an increasing inability to focus on a piece of work for any length of time he developed a reputation for not finishing writing assignments, including a proposed book on Clint Eastwood, which eventually exasperated the great man after he’d granted Nelson unprecedented hours of interview time. Proposed books on Neil Young and Rod Stewart never progressed beyond the formative stages and eventually the assignments dried up. His enthusiasm for contemporary music appeared to exhaust itseld as well and in the last years of his life he apparently only listened to bluegrass music

His last ‘proper’ job was working at a video rental store called Evergreen Video where his unreliability and increasing crankiness eventually got him the sack. From then on his health and general well-being deteriorated, his economic situation worsened and he began borrowing money from friends and concerned artists, as well as selling his precious books and records to make ends meet. His isolation and estrangement from friends and family deepened and on July 4 2006, he was found dead of heart disease in his apartment, a largely forgotten and broken man.

It’s a desperately sad story, not just because his was a disturbed life cut short but also because it seems clear that he never fully realised the great potential he had as a writer. What he did write was significant and enduring but one can’t escape the feeling that there could have been so much more. Kevin Avery does a masterly job in re-constructing Paul Nelson’s reputation and after the enthusiastic critique in the first half of the book the examples of his work in the second half do not disappoint at all. Reading these pieces several times I tried to think of someone writing with this kind of fervour and conviction today, and I couldn’t. And he didn’t just leave an indelible mark on rock criticism. Such was the esteem that he was held in at the height of his career that he was assigned to curate the White House record library – which explains why to this day it contains a copy of Trout Mask Replica.

Andy Childs.

March 2013