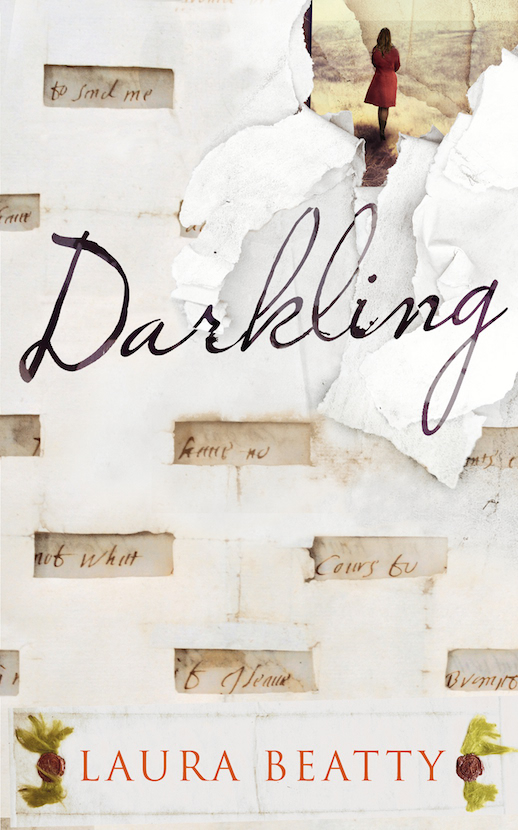

Emma Warren had a chat with the Pollard author who is about to publish her new book, Darkling.

Are you still living in Salcey Forest? Can you tell us what you see out of your bedroom window?

I live in Wiltshire now and I look out at a crazy slant of hill under a thick thatch fringe. Often when I brush my teeth, which is the first bit of looking out of the day, there is a wren looking in at me through pencilled eyebrows. Otherwise, there is a spider who I am less fond of, that lives in the overflow of the bath and last week a furious bee that had put itself behind one of the recessed lights in the kitchen. I also have hens.

Darkling is full of shifts to an animal perspective. It starts and ends with an animal perspective – a hawk seeing the world ‘like a tray, tilting’ at the start and a hawk hanging timelessly in the sky at the end. Can you talk us through some of these?

The hawk, in a sense, picks up where Pollard left off, with the aerial view from the top of the walk-way. I am very interested in perspective and how it changes the way we think about things. From the walk-way the forest looks ordered and spacious. On the ground it is muddled and compromised. It feels different. We are creatures who walk on the ground. We ought to see in close-up but we make maps, we fly planes and use satellites and take photographs and make plans in our heads or on pieces of paper, away from the things or the places concerned. We approach the world we live in, we deal with it, as if from a distance. Is this natural or unnatural? Who knows.

At a second level, I like the fact that if he goes high enough, the hawk can make us so small we disappear. I am always trying to put man into perspective. We loom so large to ourselves. Animals are a good way of doing that. They don’t know and don’t care about us. They make us irrelevant. The hawk was a way of making the present less solid, of evening things out between Mia, who is there, and Brilliana, who is gone. I was very conscious of the need constantly to balance the book – to spread the weight of past and present – and although most of the time I was busy making the past physical, I wanted also to make the present as evanescent as it really is. I wanted them to feel interchangeable.

The book is about a fictional grieving writer and a real woman she’s researching – Lady Brilliana Harley, who held out against the Royalists in the English Civil War. Why her?

I was asked to write a biography of Brilliana. That’s how the book started. It just took a different direction.

Are you interested in the different timelines of creatures and plants in the natural world? It’s a lovely additional shift in time along with the one you’ve got between Mia in the modern world and Brilliana in the seventeenth century.

In Pollard I was interested in the way that trees, as I see it, move through their lives in a spiral, coming back to the beginning with every year, while also moving on. We see our own lives as linear. We often say, ‘history repeats itself’, but there is no going back for the individual. In Darkling I wanted to collapse time altogether. I wanted past and present to be distinct in texture but simultaneous. Animals live the same way now as they did in the seventeenth century. If you watch a hare in a field, or a hawk in the sky, you have no way of knowing what century you are in, until an aeroplane passes.

How do you decide what a tree sounds like, as you did in Pollard where they became a kind of Greek chorus, or what a hawk sees?

You make it up. Then you do what Elizabeth Costello does in JM Coetzee’s novel and you listen for wrong notes. Writing for me is a lot about listening and checking back.

There’s a lyric from England by Trevor Moss and Hannah-Lou towards the end. Why that song, and those singers?

It’s a lovely song. It has something of the inscrutability of the English landscape about it – all that history, all that working and making and living, all those footsteps back and forth, and the hills just go on being green as if nothing had happened. It has something of the emotional response that landscape always seems to elicit, the surprised clutch at the heart of the moon getting up, or the sun, or the wind passing over. I like the word ‘precious’. Fields are precious in every sense. And I like the way that if you listen to Trevor and Hannah singing, you often can’t tell which is which. They swap and meld and become each other, as I wanted Brilliana and Mia to do.

What else might Caught by the River readers like to know about Darkling, or about what you’re doing, or perhaps about the forest?

I am still moving on slowly down the same chain of thoughts but it is difficult to talk about the next project before I’ve written it down. I’m aware that it possibly shouldn’t be the case but so much of my thinking is done through the writing itself. It’s too cloudy to get hold of before I get it onto the page.

Darkling by Laura Beatty is published today by Chatto & Windus. You can find it in our shop, priced £15.00