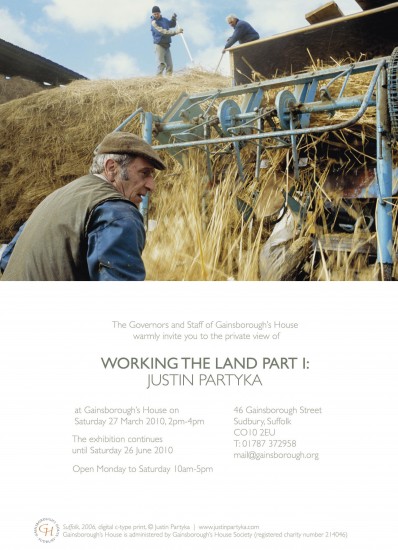

Private view on Saturday 27th of March, 2pm – 4pm. This invitation is open to all our readers. If you plan to go please print a copy of the invitation and take it along with you.

The following interview was conducted by Isabel Taylor for Albion Magazine. Reproduced by kind permission.

Justin Partyka’s work is finally beginning to garner the attention it deserves. A superbly sensitive photographer of landscapes and people, Partyka takes pictures that are mysterious and tinged with melancholy. His studies of East Anglian farmers are extraordinarily natural and dignified, while he is also adept at capturing the eloquent sky of this part of England, by turns banked with sombre cloud, a vibrant robin’s-egg blue, luminous with mist, or full of an otherworldly half-light. These unsentimental photographs capture the dust and bric-a-brac of farmyards, the spartan interiors of farmhouses, and the occasional harshness of country life. His camera extracts an uncannily profound sense of place, whether he is photographing close to home or in the streets of Cádiz. We interviewed him about his photographs, the Fens, and Eric Wortley, the 100-year-old inspiration for some of his work.

As a child were you aware of Norfolk’s agrarian heritage, or was it something that you only became aware of later on? Did you grow up around small farmers?

I was born and raised in Norfolk, in what has become a large village -or small town— on the Wash. On one side of the village is the sea, and on the other are fields and woods. I do not come from a family involved in agriculture. Of course I was aware that farming existed around me, but it was just there and not something I really thought about. This part of Norfolk is not an area of small agrarian farms, though; it is more a place of big landowners and estate farms, with their “Private – Keep Out” signs. For some reason I was typically drawn inland far more than to the coast. I would ride my bike along the farm tracks and go exploring in the nearby fields and woods, either alone or with my friends. This is not to say that I never went to the coast—I did— but it was in the fields that I felt most at home. Looking back on that time, these quiet rural places were our own little worlds that we thought nobody knew about.

Your vision of the countryside is very different from the popular image. Do you think there is a need to show people today the realities of rural life?

It is important for people to be aware that my vision of the East Anglian countryside – or wherever else I photograph – is very much my personal vision. I’m certainly not saying that my work is an objective vision, or that this is how other people should see it. It is shaped by how I explore, think about, and respond to a place, and the various things that influence me along the way. It’s all very subjective, which leaves my work open to various interpretations. At the same time, I’d like think that as I work on a project over time, eventually after digging away for a while I start to reveal a little bit of the unique sense of place that is there—or at least, that is what I try and do. As for showing ‘reality,’ that’s a very problematic term, because everybody’s reality is different. I would prefer to say that my photographs attempt to show things that people tend not to see, or choose not to see, but again it is my own interpretation of these things. Who can really say what is real?

The popular image of the countryside has become very much an idealised one, based on the safe, sanitised ideas of what people often want or expect the countryside to be. In many ways the English countryside is being turned into a giant theme park: we are told where to go and where not to go, and the landscape is being manicured, created, and controlled for our (perceived) enjoyment and safety. You have to wonder where it will all end. In the area where I grew up in Norfolk, I have noticed that the landscape is being shaped to control people, and in recent years more and more fences and gates have appeared in the countryside to keep people out, or in. It’s very sad and frustrating that this is what the rural landscape has become. Obviously we cannot stop things changing, but the only worthwhile change is improvement, and I certainly don’t see these changes as benefiting the landscape or how people experience it. Instead they are rather alienating.

Do you see yourself as trying to capture a vanishing world?

It’s a clichéd and romantic idea to suggest that as a photographer one is trying to capture something before it disappears. It follows the notion of salvage anthropology: to enter into a culture and record the last of its traditions before they become tainted by the modern world or popular culture and subsequently vanish. But for me at least, there has to be an aspect of this idea behind the work. A part of me likes to believe that the things I photograph are going to vanish, or at least experience major change, because it helps to drive the work and give it a sense of urgency. Sometimes you need these little things to inspire you to go out and photograph and do the physical work.

There’s a very strong sense of place that comes through in all of your photographs, whether they’re of East Anglia, Saskatchewan, Cádiz or Madrid. Do you consciously try to capture this sort of atmosphere in your pictures?

Yes, I think it is important to try and identify the unique sense of place wherever I may be working. After all, places are like people and they all have a specific personality. Sometimes this is very obvious, other times more subtle. I think how I conceive a sense of place is first influenced by how a place makes me feel, how I respond to its light and colour, its textures. I then try and gain an understanding of its rhythm and the traditions and culture that have grown out of the place. It’s important to be curious, to try and see the world with a childlike wonder – that way you hopefully will see things that most people would pass by. But like any of the arts, photography is very much about authorship, so how I present a sense of place should hopefully reveal how I see the world.

It is often said that my work is “dark” and for some people it’s too dark. (Perhaps I have a dark vision of the world.) I do like to photograph at the end of the day in dusk light. I find this to be a magical time: the betwixt and between hours when the landscape takes on a timeless quality in the soft fading light before disappearing into darkness. At this time of day aspects of a place come alive that had been hidden in the harsh light of the day, but it is difficult to explain exactly what these things are. As a photographer you look through a viewfinder and occasionally you see something that excites you inside and makes you press the shutter button, and you hope that this feeling is communicated in the photograph. It rarely is, but sometimes you are lucky!

Do you feel that the Fens are an underappreciated English landscape?

I think people often struggle to see the beauty of the Fens, but for me it is a very special landscape—probably the most interesting landscape of the British Isles. Even today the idea of an aesthetically pleasing landscape is still based on the notions established by the Romantics, who were typically drawn to majestic mountainous landscapes: think of the early paintings of Turner such as Llanberis (1799-1800), or the work of Caspar David Friedrich. This continued later into photography with Ansel Adams. A sublime landscape is supposedly one that towers above us, one that we look up at in awe, and desire to climb with great effort and anxious excitement, as if we all aspire to follow in the footsteps of Samuel Taylor Coleridge who became addicted to the vertigo of mountain climbing. Robert Macfarlane explores these ideas in detail in his book Mountains of the Mind. When I took Robert out to some of the fenland farms that I photograph for the piece we did together for “The New Nature Writing” issue of Granta (no. 102, Summer 2008), we discussed our feelings towards these different extremes of landscape. Robert comes from the Romantic tradition of being drawn to the mountains, and he feels at home in that kind of landscape, whereas I feel uncomfortable when faced with mountains and have no desire to climb one; I even find the Lake District an ominous place. When Robert asked me why, I half-jokingly replied “You can fall off a mountain.” In his book Robert includes a quote by John Ruskin, another mountain lover who, when faced with a totally flat landscape, reportedly felt “a kind of sickness and pain.” I’m clearly the opposite.

Returning to the subject of the Fens specifically, it is a unique landscape that in turn shapes unique people. Remember, it is essentially a man-made landscape that was drained to be worked for agriculture. The people of the Fens are part of the land on which they live and work, and having spent a lot of time there photographing, I think I can understand that feeling of intimately belonging to such a place. There is something very special about being able to see straight across a field to the far distant horizon: at times the view can be so far that it is as if you can see time coming at you. You can certainly see the wind coming! For me, from a visual perspective, the colour of the black-earthed landscape and the quality of the light from the massive sky can be extraordinary. Although it is a cultivated landscape, I see an underlying wildness there – the drained swamps are forever trying to reclaim the farmland, and most likely one day they will. There is also a mysterious, unsettling nature to this landscape, with its long straight lines of water ways and raised roads, and the scattering of abandoned farm sheds, relics from a time when agrarian farming dominated the Fens. For me, this all adds up to create a sublime place.

How did you set about gaining the trust of farmers in what must be quite isolated places, in order to take these photographs?

It is all about how you present yourself. I think I’m very gentle as a photographer, or at least I try to be, and I respect the people I am photographing. I have a quiet personality and I’m discreet in how I work; usually you quickly get a sense of how close you can work to people, when to move in and when to stay back a bit. But in terms of The East Anglians work, I’ve been photographing some of these farmers for a few years now and they’ve become my friends, so I can just turn up and photograph their lives whenever I like and they treat me as part of their world.

You seem to explore common themes in the East Anglia and Saskatchewan photographs. Is the decline of farming in general a major concern of yours?

First and foremost my work is a study of places, but mixed up in there somewhere is the influence of my training as a folklorist at Memorial University in Newfoundland. I am interested in how place shapes a culture. In East Anglia and Saskatchewan there is obviously a very rich farming tradition. Over the last fifty or sixty years this has shifted from being one of small family owned agrarian farms to the large corporate farms of agribusiness. If you drive across East Anglia today you will typically see massive fields worked by massive machines. It’s farming driven by money at the expense of losing the emotional, psychological, and physical relationship to the land. When I started photographing in East Anglia I was still living in Newfoundland, and the beginnings of The East Anglians project came out of visits back home to Norfolk. In fact the whole project only came about because I did my folklore MA dissertation on the life and work of a traditional Norfolk rabbit catcher: the earliest photograph from The East Anglians dates from 2001 and was made during my dissertation fieldwork. So one aspect of the project is me reconnecting with the region where I grew up. Through the process of photographing in East Anglia – especially the Fens – I developed a curiosity about the cultures of flat prairie landscapes, which eventually took me to Saskatchewan.

Saskatchewan is an amazing place and I felt very much at home there. There is something special and distinct about prairie life, and at times I felt like I had stepped into the pages of a Willa Cather novel. I’m pretty sure that when I first moved out to Canada to start my MA degree in 1999 I had never heard of the province, which is embarrassing now when I think about it. But I started to hear it mentioned on CBC radio and occasionally see it named in the newspapers, and once it had dawned on me that it was the centre of the Canadian prairies and essentially a place of farming I was keen to find out more. I came across a short article in the Washington Post by DeNeen Brown (Oct 25, 2003) which described how agribusiness was destroying the culture of family farms. When you consider that Saskatchewan is almost three times the size of Britain but with a population of just over one million, the significance of this cultural change becomes clear. After I’d read Brown’s article I knew that I had to go there.

It’s not quite accurate to say that farming is declining, but it is changing – or rather has changed – quite dramatically. I’m really interested in what is left behind: the forgotten small-time farmers who struggle on and try to make a living from a few acres of land, and the farms (and whole towns in the case of Saskatchewan) abandoned by those forced to quit the land. I certainly don’t want my work to be overtly political, but it does subtly hint at these issues and hopefully makes people think about them. The writings of Wendell Berry – the American writer, poet, farmer, and agrarian advocate – have been important in shaping how I think about these things.

Your work reminds me strongly of Ronald Blythe’s books, particularly Akenfield. Were you at all influenced by him?

Of course I am aware of Ronald Blythe’s work and he has recently written a nice introduction for the reissue of Adrian Bell’s Men and the Fields, but he has had no influence on my work. The books of George Ewart Evans have, though; I discovered them in the folklore department at Memorial University. Evans’ writing is still considered very important as oral history, and it is also a great model for a detailed study of a specific rural region. I like to think that the world I have photographed in The East Anglians is a remnant of the world described in Evans’ books. I have been told stories by the old Norfolk farmers I know that are very similar to those collected by Evans from the old farmers he knew in the 1950s.

Literature has been very influential in shaping how I think about and visually construct a sense of place. Pig Earth by John Berger, J. A. Baker’s The Peregrine, The Pine Barrens by John McPhee, William Faulkner, and even Thomas Hardy, all come to mind as being influential. I’ve recently been rereading Jack Kerouac’s Doctor Sax and was reminded how eloquently he depicts the Lowell of his childhood with a fantasy gothic slant; it’s very powerful stuff. When you read something like that, it’s bound to have some kind of influence if you’re open to it.

How did you learn photography, and who are your photographic influences?

I am essentially a self-taught photographer in that I’ve had no formal training, although I have taken part in a few one-week workshops taught by photographers including Ernesto Bazan, Alex Webb, and David Alan Harvey, and these have certainly helped to inform my photographic education. The main photographic influence has been John Cohen’s photo essay in the liner notes of Mountain Music of Kentucky, the album of field recordings he produced for Folkways records. As an artistic document, nothing beats this for its authenticity and completeness. Other photographers whose work I regularly return to are Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, William Eggleston, and Jeff Jacobson.

There’s a painterly effect to your photographs. Did you consciously set out to achieve this?

More than any photographic influence, the work of Vincent Van Gogh has influenced how I think about photographing rural landscapes. It’s not that I consciously go out to try and replicate his paintings, but I don’t think any visual artist has understood the rural landscape and the work of farmers more deeply than he did, and perhaps some of his sensibilities have rubbed off on me. Obviously you cannot turn a photograph into a painting, but I’m sure the appeal of a certain colour palette and light helps to achieve this painterly effect in some of my images. It is not something that I consciously think about when photographing, but I obviously make certain decisions, and I guess sometimes this adds up to more than what I expect or hope for.

Your photographs of Cádiz and Madrid are fascinating. Were they taken on the same trip? Why did you choose to photograph Spain?

I have been to Cádiz seven times now, and my work there will eventually result in a book and exhibition. I’ve tried to visit at least once every year, although I didn’t make it in 2009. My first visit, in 2004, was to take part in a workshop taught by Alex Webb and his wife Rebecca Norris Webb. I had been wanting to take a workshop with Alex and learned of this one in Cádiz, and it sounded like a very interesting place. It is a small city built on the end of a narrow peninsula. Although it is not rural, what interests me is that its location has helped to shape a very insular and unique culture. There is certainly a strong carnivalesque (in the Bakhtinian sense) tradition underlying daily life there. At the same time the city is currently going through a very active period of gentrification, and I am interested in how this will change the place visually.

My photographs from Madrid were made in 2006. I went to visit a friend who lived there, and every day I would go out and photograph. It’s a wonderful city, with great food and art, but a tough place to be in the summer as a photographer. I love hot climates, but the intense dry heat got to me a little bit. The afternoon light was very special, though.

You mention Laurie Lee in your essay on Cádiz. Is he an influence on your work?

As I Walked out One Midsummer Morning is the best writing in English that I’ve come across about Spain, followed by Hemingway’s work. Spain is still very much a country of surrealism, and Laurie Lee really captured the energy of that in his book. When I photograph in Cádiz I certainly think about the encounters he had on that journey.

I found your gallery The Place That Roger Built very interesting. Did you know Roger Deakin, and was he an influence?

I didn’t know Roger Deakin personally but I know people who did, so I knew about Walnut Tree Farm and how important it had been in shaping who he was. My photographs are just a snapshot of the place. It was my intention to go back and do more work there but it never happened, and then the house was sold and it changed, and the opportunity was gone. His writing has not had a direct influence, but there are things he said about landscape that have undoubtedly rubbed off on me.

How did the idea for My Friend Eric come about?

My Friend Eric is really the result of just playing around and realising that there was some special value in what I was doing. In March 2008 I bought a digital camera, a Canon G9, which is essentially a point-and-shoot camera but very good for its size. I realised that the camera had a video function and it’s small enough to fit in a coat pocket, so I just started carrying it around when I photographed the farmers and would occasionally get it out and film them. When I eventually looked at some of the video I realised how interesting the film of Eric Wortley was, so I just kept filming for about a year, and now and again I still do. I probably have approximately 100 hours of film now, so perhaps I should stop!

When I started to edit the film for the trailer – which was shown at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich and can be seen on Youtube – I saw that there are many ways the narrative could go, and I’m still thinking about that, so right now the film is in the mid-editing stage. I had always intended for it to have a website-based release, but that might change now. The new Apple iPad has created a lot of excitement in the photographic community as a potential new way to present work. I have yet to see one, but if video looks good on it, I’m thinking that I may release the film that way, and probably on a website too. We’ll see.

I first met the Wortleys in 2004. I was introduced to Eric by another farmer who lives nearby, and I’ve been visiting them regularly since then. And as the title of the film suggests, Eric -who is now 100 years old— has become my friend.

Eric’s reaction in the film trailer [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1aBBxJtvKeQ ] to the photo of him in The East Anglians was interesting. What sorts of reactions have you had generally from people who appear in the photos?

Yes, I thought it would be interesting to play upon Eric’s reaction to the photograph. It highlights how a photograph transforms the subject into something else and plays with reality. Sometimes you really have to look carefully at a photograph to see what is there. It is important to remember that a photograph only shows what the photographer decided to point the camera at. What I found especially interesting was how, when I combine still photographs with video of the same scene, it reveals how the freezing of a moment in a photograph visually transforms the scene into something different to what the film suggests. The opening scenes of the trailer are a good example, and you start to get a feeling of what it is like for me to photograph in such situations. It is impossible to get that feeling from the still photographs alone.

I’ve always had a very positive reaction from the people who appear in the photographs. I try whenever possible to include them in events connected to the work. A number of the farmers came to the opening of The East Anglians exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre.

It appears that you did a lot of winnowing to settle on the images you’ve included in The East Anglians. Is there any chance of you eventually publishing some of the photos that didn’t make the initial cut?

I’ve lost count of how many rolls of film I’ve used while working on The East Anglians, but it must easily be over 500 by now, which means I’ve taken 18, 000 images plus. It sounds like a lot, but it’s not. The special photographs are few and far between. This kind of photography is about exploring the world visually, and reacting spontaneously to what you discover. It is like using the camera as a sketchpad: you work quickly to try and capture the essence of what you sense is there. Not all photographers work this way, but many do. Charles Harbutt writes very well about this type of photography in the epilogue to his book Travelog.

The final selection has yet to be decided, so right now it is open in terms of which photographs will make the final, definitive cut. Who knows when and if any of the other photographs will ever be seen, but I think a photographer (or writer, etc) should only ever present his or her best work to the public. It’s difficult to articulate what makes a good photograph, but I think it goes beyond simply describing something: it has a greater quality, something that cannot really be put into words. Such photographs eventually present themselves if you look at the work closely enough. In terms of editing a sequence, you are trying to create a narrative with a flow or a rhythm. It is a lot like music, which has a big influence on my work, both when editing but also when actually photographing – it’s about creating a mood.

What gave you the idea for your new project And the Waters Will Come? What will the project involve?

And the Waters Will Come was a working title and that project has evolved into something quite different now. As I mentioned earlier I was never that interested in the coast, but I had been doing some walks and exploring it with an open mind, and I started to feel that perhaps there was something there for me to photograph after all. The threat of erosion seemed like the obvious idea to explore, but it is so obvious that it is a cliché these days – it took me a little while to realise that. Instead, I’ve spent the last year working on an intimate study of a small area of flood plain on the Norfolk coast, and I’m still making new photographs there every week. I’ve also recently been working on a new landscape project inland. Hopefully I will be presenting some work from these new projects later in the year.

When is the book version of The East Anglians coming out?

It has always been my intention that The East Anglians will be a book, but I’ve been working on the project for a number of years now, so the final book has to be right. I have a collection of various book dummies that I’ve produced, but I have yet to produce something that I feel is special enough. I’ve approached a few publishers during the last year but have yet to get any commitment. Another option would be to produce a limited edition hand-made artist’s book. My ideas for what form this book should take are developing all the time, but I feel that I’m getting close to what I hope it will be. When the book finally appears it will be announced on my website.

Exhibition: A selection of Justin’s photographs from The East Anglians series will be on show at Gainsborough’s House in Sudbury, Suffolk from 27 March to 26 June, 2010. See

http://www.justinpartyka.com/

Copyright © Isabel Taylor 2010.