by Richard King.

“So sweet and tender, cover the seed lightly, in frame or window, where the new plants are to grow”

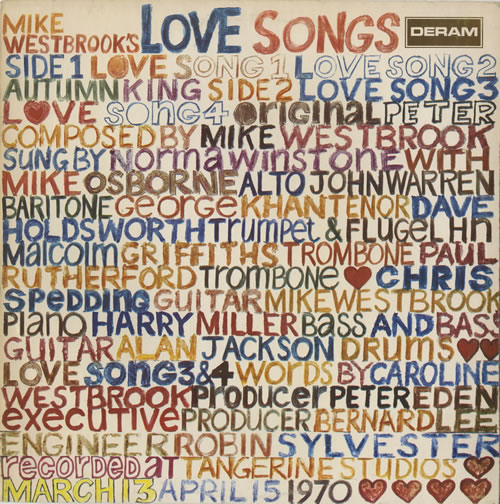

Norma Winstone’s voice, double tracked as a duet, hangs over Autumn King, the third track on Mike Westbrook’s Love Songs, like dew on a leaf. Love Songs, released in 1970 is a high watermark of intuitive, ensemble playing. The record catches a moment of grace, before the sixties fractured away into the introspection, confusion and bombast of the early years of the ensuing decade. Featuring John Surman, Mike Osborne and other luminaries of Albion jazz, on Love Songs, the Mike Westbrook Concert Band sound like the ultimate Deram outfit: exploratory, hyped up and distinctly British.

The lyrics, sung with the eroticism of new love, are borrowed from the back of a carrot seed packet, the potager’s allotment favourite: Autumn King. A dependable variety, Autumn King is harvested in September, a heavy cropper with long tapering roots and a golden hue. In Winstone’s delivery, the instructions to the gardener: ‘sew from spring until mid-June’ become a marital rite. Here is sunlight, growth, wheelbarrow paganism and starry British music in the back garden.

In St Elmo’s Fire, Brian Eno serenades ‘the cool August moon’. We don’t have the ultramarine hues of the Mediterranean in Britain. Instead we have the faded-sky pastels of the coast and the life-affirming ennui of the tide. August, despite the promise of occasional sunshine and holidays, turns cold. Now we have left the dog days of summer behind, autumn is king and September feels like the subtlest month of the calendar.

Autumn King rejoices in this subtlety: earthbound by its bass line, but fleet of foot. Time signature changes, shifts in key, and brass vamps all testify to the avant pub backroom tradition. Winstone’s authority in front of the microphone, already a veteran by her mid twenties, suggest a confidence in the sound of her own vocal abilities that is startling. This is a British music that isn’t anything but itself. Winstone’s voice, a one of a kind Thames Valley instrument, has the inflexion of an accent. Rich and lugubrious, there are subtleties to her vowels that suggest a BBC continuity announcer, or the ability to project to the back stalls of the rep theatre.

The British female voice often sounds convincing whereas its male counterpart – usually hung up on camp, class, or both – achieves only acute self-consciousness. Particularly when tied to its mother’s apron, this is of course part of its boyish charm.

This subtle confidence reappeared twenty years later in a different, but no less beguilingly parochial context. On their first two singles, St Etienne took two introspective lonely boy laments and blended them with the grains of the female voice, an intervention that feels both cinematic and liberating. For their debut, in 1990, Neil Young’s Only Love Can Break Your Heart was re-routed away from sleepy Topanga Canyon, east of the River Nile, to the minor-key melancholy of the last tube on the newly opened Hammersmith & City Line. Its follow up, sung by Donna Savage, took a more English direction that signposted the way ahead to the band’s long-term identity as Embankment auteurs. Few bands have ever found such subtlety at the heart of the city, re-mapping the grid so Zones 1-6 become a branch line tapestry of second hand bookshops, formica and allotments.

This subtle confidence reappeared twenty years later in a different, but no less beguilingly parochial context. On their first two singles, St Etienne took two introspective lonely boy laments and blended them with the grains of the female voice, an intervention that feels both cinematic and liberating. For their debut, in 1990, Neil Young’s Only Love Can Break Your Heart was re-routed away from sleepy Topanga Canyon, east of the River Nile, to the minor-key melancholy of the last tube on the newly opened Hammersmith & City Line. Its follow up, sung by Donna Savage, took a more English direction that signposted the way ahead to the band’s long-term identity as Embankment auteurs. Few bands have ever found such subtlety at the heart of the city, re-mapping the grid so Zones 1-6 become a branch line tapestry of second hand bookshops, formica and allotments.

Savage’s accent, the way ‘Up’ ever so slightly becomes “Uhp” has twice the resonance of her male contemporaries, hunched as they were, in front of the microphone, flattening their vowels to fit into their baggy clothes. Kiss And Make Up, originally written and recorded as a bed-sit confessional by The Field Mice is set loose onto a Balearic breeze, the promise of reconciliation offered as a sensual contract. By replacing the original’s wet blanket apology with a Roland 909, St Etienne sound like they really know how to kiss. The Field Mice, for all their wounded ambience, sound like they need a hug – which, while perhaps not quite so exciting, is no less an emotion.

“There’s light at the end of the summer’’

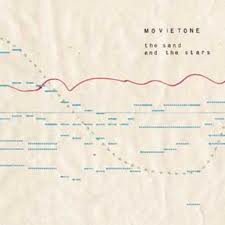

Kate Wright of Movietone sings with one of the most English voices ever sent to tape. On 2003’s Beach Samba she sings ‘theatre’ with a RADA approved pronunciation of ‘thee-eh-tah’; the confidence in her quiet delivery given added resonance and strength by her Bristolian burr. Recorded live on a two-track under the stars, on the beach at Porthcurno in Cornwall, Beach Samba, with brass arrangements and a loping English sense of mystery brings us back to Autumn King.

These are pastoral sounds that resist the inflections of Celtic tunings or folkish tropes to record the landscape. Listening to Movietone, you can literally hear the waves. As a result, it has the startling authenticity of an autumnal walk along the beach, taking the British inner journey, so often an urban or suburban daydream, for a breath of fresh air.

From the allotment, to the coast, then back; this might well be a dream trajectory through the cycle of the British seasons.

The harvest of Autumn King is gathered in and the seed heads, in readiness for next year’s liminal transformation, are collected for next year’s sewing. A subtle process of renewal at this shimmering point in the world.