By Maurice Gorham and Edward Ardizzone

Review by Andrew Male

“What a very useful institution the local pub can be.” – Maurice Gorham.

It is September 1939, and in the London offices of The Radio Times, Art Editor Maurice Gorham is putting the finishing touches to his monograph on the London pub, The Local. Written under the heavy cloud of imminent conflict, his thoughts are weighted with a valedictory sadness, shrouded in the inky raiments of the wartime Blackout. “The lights went first,” writes Gorham, “The enormous lanterns of Victorian gin palaces, the warm glow through the red curtains of the cozierpubs… We grope our way to pubs nowadays, as though they were speakeasies…and when we get there we find them full of strange patrons.”

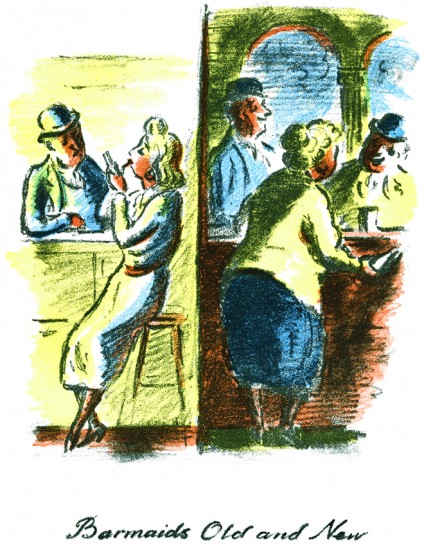

With the potmen called up, the barmaids sent home, and Gorham himself soon off to become the Director of the BBC’s North American Services, all was change in the “very useful institution” of the local pub. However, this wasn’t just the fault of the Second World War. Gorham also noted the effects of a far more sinister blight… “the “bright young people”.

A left-leaning, Oxford-educated journalist, Gorham was writing in the wake of Mass Observation, the 1937 social research organisation founded by Tom Harrisson, Charles Madge and Humphrey Jennings. Like Harrisson, Gorham recognized the scientific importance of recording the social customs of “the man in the street”. But unlike many of the often gossipy Mass Observation surveys, Gorham’s writing bestows a strange protective dignity upon the regulars of the local, observing their rituals with a hushed, scientific clarity, as if this were a field guide, allowing you to communicate with the aboriginals in their native language. All is guidelines, requisite tools for getting by, often delivered with a wry humour.

Gorham is excellent on the divisions of the local pub, both literal (the vital differences in furnishing and decoration between The Saloon Lounge, the Saloon Bar and The Public Bar) and social (“there are many public bars where any patron not dressed as a labourer is regarded with distrust”). He is even better on the infinite complexities and varieties of pub beer: “In London pubs, ale stands for Mild Ale, which is the mildest sort of beer. It is reddish-brown in colour, not unlike Burton to look at. Mild ale is also drunk mixed with bitter (Mild-and-bitter), Burton (old-and-mild), strong ale or stout. If you ask for a beer in a London pub without specifying what you want, you will probably get bitter.” There is even a Glossary at the back, a thing of beauty, educating the neophyte in the history of Burton ale, the derivation of “swipes”, “rough”, “wompo”, and “wollop”, recommended tipples (“Wine in pubs is a thing to avoid…draught beers take knowing”) and the vernacular names for a pint of old-and mild (“granny”), or stout-and-bitter (“mother-in-law”).

Yet, like so many social anthropologists,Gorham is a self-admitted “sentimentalist”, protective of his adopted tribe (“Every pub is somebody’s local”). He venerates the class segregations that exist in the pre-war pub, is suspicious of modern rebuilding projects that would do away with the snob screens, snugs and cubicles, and favours the “quiet, intellectual” pursuit of dominoes over “the darts craze”, that saw middle-class white-collared workers entering the public bar while “the regulars sat gloomily in corners , talking in undertones”.

In fact, Gorham sees nothing but destruction in the annexation of the Local by these “bright young people” and their “hard-boiled charm”, and is beautifully wrought 1939 account of their tyranny may still ring some bells of recognition today. As such, it is worth quoting in full:

It is a terrible thing to see a quiet, ordinary pub in process of being discovered by the bright young people, who are becoming increasingly fond of going to pubs. Their penetrating voices and scarlet fingernails soon come to dominate the Saloon Bar; the craze for darts may even bring them swarming into the cheapside. The pub that caters for them begins to go downhill. The local regulars abandon it and go elsewhere, the staff suffers a change. If redecoration has not already happened, it happens now. At this stage the bright young thingsoften change their habits and desert the redecorated house for another, leaving a wreck behind. Few pubs can thrive on their patronage. If it lasts long it may mean ruin; the sorts cars outside the door are as ominous to the licensed house as the hire purchase vans, taking back the furniture…”

Gorham’s point is that these middle-class usurpers had no true attachment to the pub. To them pub-going was a game, anovelty that they would eventually tire of – Marie Antoinette dressing up as a milk-maid – or another rung up on the ladder of cultural procurement, like those Cath Kidston-kitted modern armies who moved into the local allotments two years ago but have now abandoned their plots because it was too much like hard work.

Cultural spaces should be sites for life, believes Gorham; they are a job of work. “When a nice old pub is pulled down and turned into a cross between a roadhouse and a sanitorium it is the regulars who suffer….” he writes. “It is a sad ending to a modest and not altogether useless career.” Career. Isn’t that great?

The surprise of The Local is that Gorham’s pub aesthetic, however sentimental, still resonates powerfully today. Read his description of The Warrington in Maida Vale, where “the mere sight of the staircase makes you think of Edwardian revelry, of well-nourished book-makers and stout ladies in cartwheel hats, of feather boas and parasols and Malacca canes, of dogskin gloves and fat cigars”. Then visit their current website. It is now a Gordon Ramsay gastropub offering “Freshly sourced seasonal produce for hearty British pub dishes [with] a number of areas of the restaurant just perfect for hosting your corporate party.”

A pub is for life, not just for business.

Yet, Gorham’s words are only half the pleasure of The Local. Anyone familiar with the reputation of the book will be wondering why no mention has been made, until now, of the book’s illustrator, Edward Ardizzone. Well, Ardizzone is worth saving, and savouring.

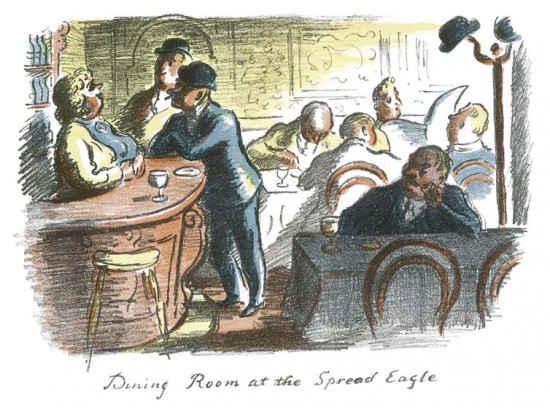

Born in 1900, in Haiphong, Tonkin Province, French Indo-China, to an Italian father and a Scottish mother, Edward Ardizzone was privately educated at Clayesmore School but took evening classes at Westminster School Of Art, eventually giving the elbow to life as a respected London businessman for that of a full-time artist. Most famous for his wartime drawings of the Blitz, the Home Guard, El Alemain and the Normandy Landings, Ardizzone possessed a loose, playful, fluid style that captured the everyday, everyman qualities of human beings in extraordinary circumstances, moments of prosaic familiarity and fleeting beauty; the hushed roadside conversations, the shared joke, the stolen kip in a ruined copse. As such, his colour illustrations for The Local, can be looked upon as his urtext, setting down the essential values of cosiness, community, contemplation and camaraderie that he would continue to seek out in his war-work and beyond.

When coupled with Gorham’s romantic, kind-hearted prose, Ardizzone’s images – quiet Saloon Bar contemplation, lamp-lit groups of revelers finishing up pavement conversations after closing time – reveal The Local’s true purpose: it is the pre-war service manual for the British pub; how to run it efficiently and how not to break it.

Ironically, the original publishers of The Local, Cassells, were bombed in the war, and all litho plates and unsold copies of the book were destroyed in the blaze. A post-war follow-up, Back to The Local, was published in 1949, but this is the one to track down. Now beautifully reprinted by Little Toller Books in blue-cloth hard-back, it is a slim, handsome, stout-spined thing. Carry it with you at all times, and when the next wave of middle-class locusts swarm through your local (or allotment, or fishing village) you can loudly declaim Gorham’s “bright young people” diatribe. In an ideal world, they will realize the error of their ways and retreat. Failing that, you could always crack them across the head with thebook. It’s a sturdy little thing.

The Local is on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £15.00