This month from Nina’s neighbours ‘The Children’

It’s eight years since Armorel and I first turned up Grange Lane in search of a better life. When I saw that sign, “Gun Site Allotments”, I thought, that’s going to end up as a poem. The heavyweight champion that you have to face in this arena is Virgil, with his four-part poem about farming known as the Georgics. His four sections aren’t the four seasons, though: they deal with, first, different kinds of land, then different kinds of crops, then herds and flocks, and finally beekeeping. Or as Dryden, his best English translator, pointed out, with an ascending sequence, from the mineral through the vegetable and animal to the social. There’s a poignant subtext there, because the Roman republic was tearing itself apart in catastrophic civil war while Virgil was writing about the peaceful (though none too democratic) community of the bees. Fortunately, you don’t have to go up against Virgil alone: there’s a gang of English poets to back you up. I was particularly encouraged by James Thomson, a Scot, whose Four Seasons was highly regarded throughout the eighteenth century, though not much read now. It gives the lie to the notion that no one noticed the countryside until the Romantics came along.

I did give the poem a good old-fashioned Latin epigram, though, from the Georgics. It comes from a passage about an old man whose land is too poor to graze cattle on, or grow wheat or vines, so he grows vegetables. Virgil says: “praetereo atque aliis post me memoranda relinquo”. Which means (so I’m told): “The recording of such things, however, I leave to others after me”. Which seemed a two-thousand- year-old open invitation to at least have a go. Here’s part of The Gun Site that deals with our present season, with Nature’s great closing-down sale (everything must go).

Twining stems of the beans, wrapped tight to their poles,

are flagged with the leavings of fertility,

a few leaves and a few twisted, vivid beans,

and the last rows of tomatoes, shrivelled stiff,

have made their fruit the sweetest in their decay.

Rocket and lettuce gone to seed. Piece by piece,

the ground’s put to sleep with its blanket of dung.

The living, meanwhile, remain to attend to

and the food they give to gather. The apple

trees swathed gracelessly in netting, in odd bits

of net wired together against the robbers,

the rooks and squirrels, stand like Magritte’s woman

with sheet-veiled face, hand to her throat (a ghost of

childhood recurring, of his drowned mother’s form).

Work your head through a gap of the enclosure:

the apples seem in possession of their space,

illuminating the somewhat-less-than-day

underneath caught leaves with a magical red

as if warmed within. Some near-bitter oil shields

their skin, but a bite explains they’re cool, then sweet,

fat with summer’s wet, with almost too much juice.

And now the small cherry tree with its large leaves

has sung the days backwards, from clear noon yellow

to a dawn-dark red, till retreating flames leave

nakedness. It barely stands to our shoulders,

with limbs that are longer than ours, whose handfuls

of lustrous fruit the birds stripped in a morning.

And now its twigs are tagged with the points of spring.

There’s still a spell of sun in the afternoon

when the world seems cleanest, all done with a blue

and orchestral green and yellow. The oaks go

slowly through their preparations for a fall

and mingle its varied stages on each branch.

From the heavy shades of their writhen timber

the leaves they are set to shed seem lighter still.

And still there’s the spell when a single maple

makes of itself a gilt sky, falling piecemeal,

while the sycamores are publishing, under

every step, masterpieces on the pavement,

even on that morning when the door opens

to a hostile air that’s muttering about snow

and a sideswipe gust, raw from lowering cloud.

Still to come, the oaks undoing their deeper

kind of gold to fledge with rust-wrinkled iron;

and just gone, the October day when a breeze

breathes heat for the last time and you and a friend,

beside the concrete sphinxes on stoic guard

of the Crystal Palace’s non-existence

admire the gentle suburban hills of Kent.

Out there, Palmer unfolds his English idyll,

fields where Arcadia ripens to Paradise:

Palmer the pilgrim who enters on his way

through the visions of the Interpreter’s House –

Fountain Court, off the Strand, the home of the Blakes.

When Samuel and William walk Sydenham Hill,

the Rye, Goose Green and Dulwich, these oaks are there.

Midnight in the old villages, heading south.

The wooded slope where the Gun Site lies hidden

shows no lights. It touches its intricate dark

to the simple dark of the sky and draws down

nearer the city’s timid remnant of stars.

Obscure foam cresting the horizon. That wave’s

long blank feels good against our burning fever.

*****

Here’s Armorel’s recipe for some of the final fruits of the year.

(From here on in, we’ll be subsisting mainly on roots and brassica leaves, in all their various forms.)

Fresh Tomato & Basil Linguine (served with Kir Spritzer!)

If you’ve still got tomatoes on your allotment, or your balcony or windowsill, real pasta sauces are the ultimate easy, quick and delicious dish to use them in.

One onion, finely chopped, in a good slug of finest olive oil, fried till transparent.

Add one crushed clove of garlic per serving to the onions.

While that’s cooking, put the tomatoes in a bowl and pour boiling water over them.

Leave for 5 minutes or so, till the skins come off easily.

Put them straight into the pan with the onion, leaving the skins in the bowl. (You can use this water to cook your linguine.)

Take a large bunch of basil, snipped carefully from your plant, chop and add to the tomatoes and onion, and add seasoning.

Drain the tomato skin water into a large pan, top up with boiling water, a bay leaf, salt and a spoonful of oil.

When the pasta’s cooked, add to the tomato pan and toss in the reduced sauce.

Serve with a good mixed green salad and grated parmesan.”

Our tipple at the moment, which is quite sweet but goes perfectly well with a fresh tomato pasta like this, is what might be called Kir Spritzer. Kir is a French aperitif, a mixture of crème de cassis (blackcurrent liqueur) with white wine. With champagne, it’s Kir Royal. Good old Wikipedia has just told me that Kir was actually the name of a mayor of Dijon after the second world war, who popularised the drink (Dijon being a famous producer of crème de cassis).

We make our Kir Spritzer with, approximately, one part of crème to six of wine, then top this up with half as much again of sparkling water. We’ve experimented to see how far down the price range of white wine you can go and still get a pleasant result, and the answer is, pretty far. Thinner white wines, like Pinot Grigio, are better than cheap sweet ones, though. It’s a fairly sweet drink, so a dash of dry vermouth can offset that nicely. Not too much, mind – or you’ll lose the flavour of the fruit.

During the summer soft fruit glut we made crème out of everything – blackcurrants, but also tayberries, loganberries, raspberries and blackberries. You might still be able to make some from the latter, if you’re lucky (the French call this crème de mûre). The recipe came from Hugh Fearnley Whittingstall in The Guardian, and it’s so simple that even I can remember it, because it’s mostly even proportions.

Method:

Put 1 kilo of fruit in a bowl and pour over 1 litre of a reasonably good and fruity red wine (or 500g to 500ml – you get the idea). Leave it to steep, covered with a cloth, for 48 hours.

Put it through muslin: it won’t drip through of its own accord, give it a good squishing.

Transfer the liquid with a measuring jug into a large heavy pan, and then measure in an equal volume of sugar. I usually used granulated, but soft brown might give you a marginally better flavour.

Now for the only slightly tricky part. Heat the liquid, stirring occasionally, to only-just a simmer, but don’t let it boil, and keep it there for about 40 minutes. If you cook it too hard, it’s not ruined, but your lovely syrupy crème will take on a slightly gloopy quality.

Finally, measure your liquid out again, and fortify it 1 part to 3 with vodka. I sterilised bottles in the oven at 100C before funnelling it in, but with the alcohol content it’s probably not essential.

We’re still exploring the uses for this delicious stuff: it’s lovely as a cordial, for instance, about 1 to 10 with sparkling water. Quick, hunt down those last blackberries, or autumn raspberries.

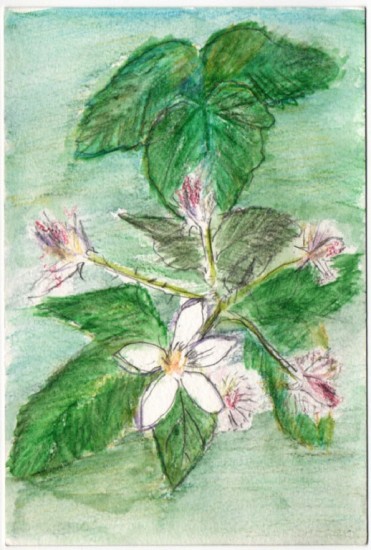

I don’t have any pictures of our berries, I’m afraid, but here’s what they looked like in their early childhood.

Click here for previous instalments of Allotment Watch