In which, as the year comes to its end, our friends and collaborators look back and share their moments:

I look around this desk and see the usual detritus: receipts, train tickets, lists, disregarded mail and a larger than usual pile of half-started books. There’s a permanence to this build up of debris which reinforces the feeling that for most of the year, in terms of sitting at my desk and working, I’ve only really been passing through. These piles are testament to a certain type of inertia, one which ensures being busy is far less productive than hours spent apparently lost in dead wall reveries or dredging slowly through the past. My first book was published in April and I spent a great deal of time, much of which was wonderful, promoting it.

Apart from a rogue three-day heat wave April and May were especially cold. From train windows I kept a keen eye on the allotments that are so often found near stations; nothing was growing in our patch and I found myself constantly scouring the municipal ground for shoots and seedlings or any indication of change. The first allotment boom in Britain was a result of the Great War. The mainland naval blockades meant there were food shortages and any suitable space was given over to the growth of produce. The railways were considerable landowners and the pastures and scrub around stations were turned over to the war effort. The ground was dug and sewn into vivid patchworks of individual and labour-intensive market gardening. By the time of the Beveridge report in 1942 there were around a million and a half allotments in Britain, all of them providing necessary accompaniment to the frugal pickings of rationing. Whenever I board a train these days my time seems to be suspended in a listless compromise. What felt like weeks if not months were spent contentedly staring at canes, plastic bottles and modest piles of gardening equipment all willing the plants to grow.

Peering out through rainy train windows for signs of life in one of the last vestiges of the post war settlement. As a metaphor perhaps it’s something of a stretch, but it seems to me to sum up the national mood of 2012 more accurately than any flag waving.

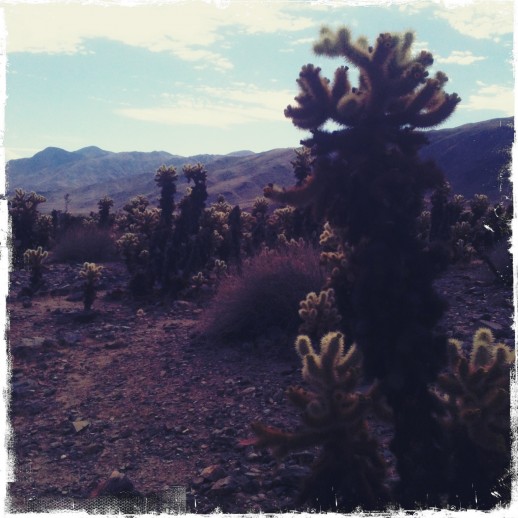

The bees finally arrived at the end of July and the growing season was condensed into a six or seven week binge that extended well into September. I spent part of that month in the Mojave Desert. I had gone there to see the landscape in which Don Van Vliet had lived and painted and to hear its murmur at night and to imagine the heat on his back as he immersed himself in the horizon. One morning a raven stood next to us on the trunk of a collapsed Joshua tree. It lingered awhile, shuffled and squawked then noisily flew away. As I looked up at its fan shaped tail cut through the heavy air I realised we were in exactly the right location.

I’ve met some remarkable individuals this year and have been able to spend time with friends who I don’t see enough. But whatever joy I have felt has been tempered by the fact that too many people I know are suffering. It’s a particular kind of suffering, not merely a tap on the shoulder from fate indicating it’s your turn, or a nasty run of bad luck, but a sense that people’s lives are being made unnecessarily and deliberately harder. We seem to be living under a settlement that feels mean and futile, one that feels a considered reflection about the findings of the Hillsborough Independent Panel report is not enough and that any response to such a report has to be accompanied by a running commentary on how well the Prime Minister delivered his lines. I’m as bewildered as anyone else as to quite how we’ve arrived here, but looking on at the uncompromising dignity of the families of the ninety-six and as names like Orgreave re-enter public debate, it’s hard not to feel warmth and optimism at the spirit that runs through this remarkable country.