Writer Sue Brooks picks up where she left off in January – the Antarctic – as she continues with the incredible story of Edgar Evans and the Terra Nova expedition, 1910-1912…

On July 20th 1911 in the depths of the austral winter when the sun sinks below the horizon for 4 months, Apsley Cherry-Garrard fell on a snow slope and both the Emperor Penguin eggs carried inside his fur mitts cracked. The first I emptied out, the second I left in my mitt to put in the cooker; it never got there……Of the five eggs collected at Cape Crozier, three survived, and one is on display at the Natural History Museum at South Kensington.

I’m on my way there at last. It’s March 20th 2014, one hundred and three years and four months after the day a fertilized Emperor Penguin’s egg was held by a human hand. I’m walking through the underpass and along Cromwell Road towards the revolving doors of the building that never fails to take my breath away. I buy a Souvenir Guide from a young man who tells me he practises his writing between shifts. What do you write about? Anything he says this place is so inspiring.

Darwin sits, wracked in thought, at the top of the central staircase, wishing, I have no doubt, that he could be at home in his beloved Down House. Alfred Russell Wallace in the painting beside him, looks benign. I imagine the only sentence I know from The Origin Of Species displayed as a huge banner behind them -THERE IS GRANDEUR IN THIS VIEW OF LIFE. I say the words under my breath and take the last few steps to the Cadogan Gallery which the Guide tells me, contains the Icons. 22 objects chosen from the 70 million in the collection. Objects of reverence, some of which shook our world view. Others highlighted our responsibility as custodians of the natural world. All have fired imaginations. Indeed they have. Is this the reason above all others that I am here? Is is that simple?

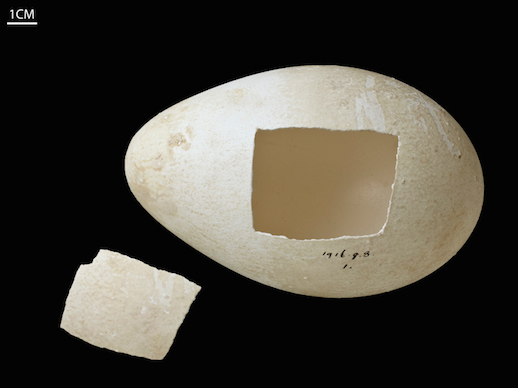

Each icon is alone in a black display case lit by a single spotlight. I take the anti-clockwise route past the Archaeopteryx fossil, a first edition of The Origin Of Species ( Constable 1859 ) and a tray of butterflies collected by Alfred Wallace. The Emperor Penguin’s egg looks like an alabaster jewel in its black case. A rectangular hole has been cut out of one side and beneath it I can just read in black ink, the numbers 1916.9.8. Evidence of the three years of obscurity after it had been delivered to the Museum in the hands of the sole human survivor in 1913. Another one hundred years would pass before it emerged as a sacred object.

As I flick through the information screen beside the case, a new photo appears. The one taken soon after the three men arrived back at Cape Evans, the one Henry Ponting is quoted as saying would haunt him for the rest of his life. I study the faces of Edward Wilson and Apsley Cherry-Garrard ( Bowers is turned away from the camera ) staring blankly through eyes that have been in the dark for almost 2 months. These are men who endured temperatures night after night as low as minus 70 degrees. Again and again Bill asked us how about going back, and always we said no. Yet there was nothing I should have liked better. I was quite sure that to dream of Cape Crozier was the wildest lunacy. That day we had advanced one and a half miles by the utmost labour and the usual relay work.

Relay work started on Day 3 of The Winter Journey when they realised three men could not pull the combined weight of two sledges, each one piled high with equipment – a total of 790lbs. If there was no Arctic wind or glimmer of moonlight, the relay trip for the second sledge was often done by candlelight. Three figures in the vast frozen darkness moving by the light of a single candle. It has a mythic quality: an austral Holy Grail. Like everyone else who has read, and probably reread “The Worst Journey In The World”, there are certain details which catch the heart, and for me, it has been the candle, and, so very endearingly, the pyjamas. Just writing the word makes me want to laugh and cry. Did they really do this? But there it is on page 278 where Apsley Cherry-Garrard is describing the collapse of the igloo in the blizzard : our pyjama jackets were stuffed between the roof and the rocks over the door. The rocks were lifting and shaking here till we thought they would fall.

Alan Bennett understood it, I think. Guy Burgess, in the play An Englishman Abroad, has all his wishes about Englishness granted, except the pyjamas. The striped red and white cotton ones I’m sure; the same English pyjamas which went to Cape Crozier and provided comfort at -70 degrees Fahrenheit.

I can feel the imagination tightening its grip. Searching for an antidote I come across Francis Spufford’s I May Be Some Time. Titus Oates stumbles to his death on the cover followed by the subtitle on page 5 – “Ice And The English Imagination.” Spufford devoted 6 years to researching the romance that has waxed and waned around the Polar expeditions. It is magnificently realised: it enthralled me to the end. And then there is an Epilogue. Two years after the publication of the book in 1996, he travels to Antarctica on a Russian tour ship. He stands on Observation Hill and thinks about each of the dead men.

I can picture them: I know things about them that they did not know about each other……and yet as I gaze from Observation Hill, I find myself admiring them more, not less……They learned the land minutely. They grew more intensely present in it. Dr Wilson wrote a poem of rapture –

We might be the men who were meant to know

The secrets of the barrier snow.

When it is time to leave the cairn with its 9 foot cross, which Spufford, ever attentive to detail, tells us has been blown down twice in polar blizzards, he finds a way to do it alone where his tears cannot be seen.

Is this what I needed to know? I have kept faith with the image from childhood, resurrected so surprisingly in the photo of Edgar Evans on the Gower, leading me past Charles Darwin and the Egg-as-Icon in the Natural History Museum gallery, and still it leads me on. Past Francis Spufford in his post-Romantic grief, to the man who is now more flesh and blood than all the others. Edward Wilson: artist, naturalist, Antarctic explorer and mystic who went up into the Crow’s Nest on Terra Nova to say his prayers. As a young man he wrote in a letter to his sister Once or twice I have seen heaven. I painted a primrose there. Unlike Darwin, he found no conflict between science and faith; science was a way of paying exquisite attention to the natural world. The painting of the primrose and the extract from the letter are illustrated in the Guide to the Museum that bears his name in Cheltenham. I went there last week. The Wilson Gallery in the vast building is no more than a large cupboard. An expedition sledge, narrow and heavy, made of solid wooden runners, and a pair of finnesko, the reindeer skin boots they all wore, lie behind a glass partition. A life-sized photo of Wilson is propped against the wall like a Kodak advert. He is smiling faintly, as if we were about to shake hands. I smile too, and say hello.

This is the reason I’m here. Not for the madness of The Winter Journey, but for the extraordinary qualities of the man who led it. He was willing to risk his life to contribute the missing link in the evolution of birds. Not for fame or reputation, but for the advancement of knowledge. Between the two Antarctic expeditions, he lectured and campaigned for the protection of the Emperor Penguin, and exhibited his drawings and paintings to raise money for the Terra Nova. The Winter Journey took on a life of its own and became a mission. It had to happen.

On the floor below the Wilson Gallery, through a fire door, I enter the Paper Store. The room is scrupulously air-conditioned and low-lighted to protect the memorabilia laid out in white cabinets. I am alone. I peer at the family albums: Edward aged 9 months, 8 years, at Cambridge with other students. His marriage to Oriana. The formal dress of the Edwardians on nearly all occasions. Edward sketching in his favourite place – his mother’s farm at The Crippets. Three of the drawers are marked OPEN. They slide out silently to reveal more photos, mostly of Antarctica, and the penultimate letter written to his wife from the tent in which he died.

Death hold no terror for me…I know we shall meet again. We are pretty done in. One of Cap Scott’s feet is frostbitten. Deeply, deeply moving to see his handwriting – clear, even, the words running in straight lines across the page of a small notebook. His friend called Cap Scott to the end.

I pause at the door. There is an unearthly silence in the room. No sound from the air-conditioning despite the strange quality of the air. It reminds me of the funeral parlour where I went to see my father’s body. I think of Atkinson taking the diaries from the bodies in the tent and shutting himself away in his own tent to read the story we all now know so well. The bible which was used bury Scott, Wilson and Bowers is above my head in the cupboard gallery. It is open at The Burial Of The Dead. A small group of men in the vast white wilderness, one voice speaking into the silence. We each make our own journey with these men. This has been mine. I close the door and leave them there.