Of Green Leaf, Bird and Flower: Artist’s Books and the Natural World.

Edited by Elisabeth R. Fairman.

Yale University Press, New Haven and London

Review by Sue Brooks.

Just looking at the front and back cover of this beautiful publication, the ribbon markers which match the colours of the illustrations, and the little specimen pocket which must have been attached by hand to each copy, I knew I was in for a treat. This is the physical book as an art object, and fittingly so since it accompanies the exhibition of the same name which is running at the Yale Centre For British Art until August 10th. Although inspired by the exhibition, it is a far from being a conventional catalogue. I was astonished to know the range and size of the permanent collection: it is the largest outside the UK, much of it the work of landscape artists and natural history collectors from the 17th to the 21st centuries. Elisabeth Fairman, Senior Curator at the Centre and curator of the present exhibition, has a particular interest in artist’s books and has added many contemporary works in recent years. Her knowledge and enthusiasm spill out in her introductory essay, and her tirelessness in doing justice to the beautiful objects in her care.

(7) The Language of Flowers, ca. 1860, chromolithograph, cut and folded paper. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund.

(7) The Language of Flowers, ca. 1860, chromolithograph, cut and folded paper. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund.

The book is printed and bound in Italy. The designer – Miko McGinty is given a full page credit with a delicate illustration of a poppy by Mandy Bonnell ( Wild Flowers Worth Notice 2012 ) and the photographers of each exhibit are named individually. Nothing has been spared to present the work in the best possible colour and light. The journey has been arranged in two sections. In the first we are in the company of Molly Duggins, art historian from the National Art School, Sydney, Australia, Robrt McCracken Peck, Senior Fellow of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and David Burnett, poet and collector of wood engravings. Each contribute an extended essay on a particular aspect of the exhibition, lavishly illustrated with photographs. In Elisabeth Fairman’s words, These three essays provide the reader with a solid footing for the journey through the flora and fauna of the British countryside that follows.

The second section opens dramatically as a double page spread of a Victorian album showing a display of dried flower and seaweed specimens on one side and the title Field Guide to the British Countryside on the other. The person who picked the poppy, fern and buttercup 155 years ago at Beyton, Rougham, Bury St Edmunds in August and Sept 1859, and arranged them so artistically in the album, is unknown. We can imagine her though, as have many of the contemporary artists who have drawn inspiration from the self- taught naturalists of the past. The juxtaposition of images and short texts, both contemporary and historic illustrate the common threads which allow them in the Field Guide, to walk hand in hand.

If I pull out anything for particular pleasure, it would be David Burnett’s introduction, as it was for me, to Sister Margaret Tournour, Wood Engraver, Naturalist and Catholic convert who entered the Society of the Sacred Heart age 30, giving up all her worldly goods including her engraving tools. They were not restored to her until her retirement. The exquisite work presented in the book was done in the last 20 years of her life, when she was confined to a wheelchair. David Burnett compares its surreal, mystical quality to Samuel Palmer and Blake (interestingly a pencil sketch by Palmer of a bramble, complete with measurements and the traced outline of a single leaf is included in the exhibition.)

Another would be the delightful Miss Rowe who joined Liverpool Naturalist’s Field Club in 1861, aged 19 and competed for the annual Botanical Prize for an arrangement in natural order, of wild flowers. Miss Rowe’s collection of 500 was housed in a wooden box, each one inside a blue stationery envelope with a water colour drawing of the specimen on the outside. The simple lines of the poppy and the faded and slightly ethereal blue of the envelope on page 20 are very moving. In fact, all the blues, and there are many of them, of various shades and subtleties throughout the book, are especially striking.

Edward Lear, Feathers from Family Album (fol.8), 1828-1836, natural specimens and watercolour. MS Typ 55.4, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Edward Lear, Feathers from Family Album (fol.8), 1828-1836, natural specimens and watercolour. MS Typ 55.4, Houghton Library, Harvard University

It is unlikely that I or any readers will be able to visit the exhibition so near its final day, but this book is a lasting testament to Elisabeth Fairman’s vision. It would be a wonderful addition to the library of any naturalist or artist. A feast for the eyes and a sharpening of acute observation of the natural world, especially, as David Burnett says of Sister Margaret phenomena which might at first sight appear slight or insignificant. Her purpose is not to close or settle, but to open and illuminate – a dandelion for example, or a teasel.

As a postscript, I was delighted to learn from the acknowledgements that grateful thanks were given for the enthusiastic interest and support of (Caught by the River contributor) Cheryl Tipp, Curator, Natural Sounds, Sound and Vision, at the British Library, who has compiled a selection of bird songs and sounds of the British countryside for the exhibition. Lovely to think of walking through a door in New Haven, Connecticut to the sounds of blackbird and sheep.

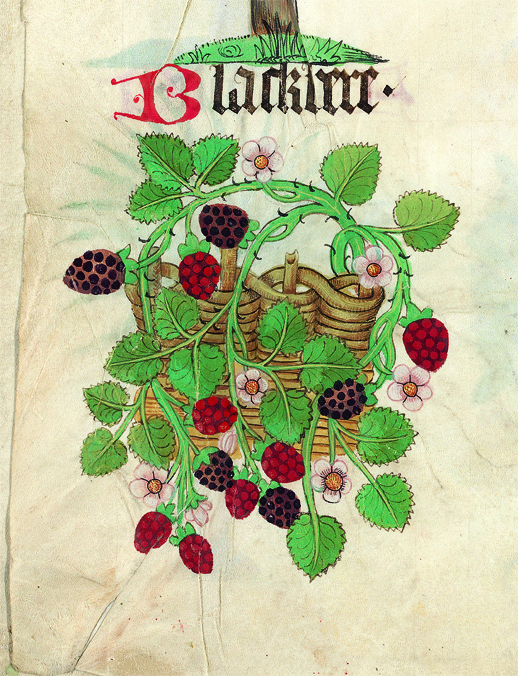

“Blackbere” from Helmingham Herbal and Bestiary (detail), ca. 1500, watercolour and gouache on parchment. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

“Blackbere” from Helmingham Herbal and Bestiary (detail), ca. 1500, watercolour and gouache on parchment. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection William Lewin, Common Hoopoe, ca. 1789, watercolour and gouache over graphite. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

William Lewin, Common Hoopoe, ca. 1789, watercolour and gouache over graphite. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.