Having traversed the same bridge – both ways – for our Port Eliot sojourn just the other week, Travis Elborough digs up a very British vintage travelogue capturing the joys of the Cornish coast…

1961 saw the opening to traffic of the Tamar suspension bridge between Saltash in Cornwall and Plymouth in Devon. That same year, the British Travel Association produced a film entitled Westward Ho! to promote tourism in the south west.

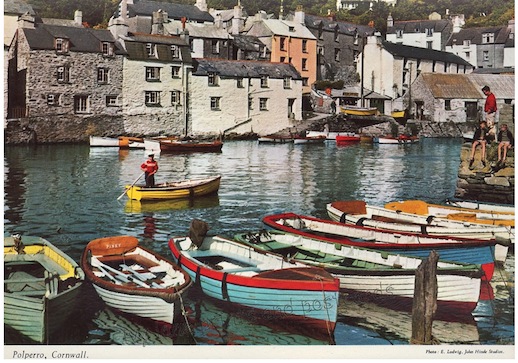

Narrated by the fruity-voiced Plymouth-born thesp Paul Rogers and top and tailed with a rousing score by Philip Green, the prolific film composer responsible for lending Carry On Admiral and Sea Fury suitably nautical, musical ballast (cue hornpipe refrain in any opportune scene), it depicts a Cornwall (and bits of Devon and Dorset) of sandy beaches, craggy coves, mossy cliffs and rocky harbours. A region of endless sunny days, dinky boats, whitewashed cottages, beamed inns, thatched eateries and olde worlde curiosity shoppes. One peopled almost exclusively by jovial, pipe-smoking fishermen in caps, ruddy-faced publicans, respectful guesthouse owners, ever-attentive waitresses, painters in oils-splattered smocks and crinkly eyed rustics who never miss an opportunity to show visitors the correct way to line a rod or bottle a matchstick ship. Or, when a pewter tankard of ale is handy, to regale them with yarns about smugglers and the salting of pilchards in days gone by.

As the script constantly underlines with its references to ‘agelessness’, ‘unchanging villages’, ‘picture book places’ and ‘fairy whistle stops’, King Arthur at Tintagel, King George’s men on the prowl around Burgh Island, Drake and bowls at Plymouth Hoe and Thomas Hardy in Dorchester, the film is as much a magical trip back in time as a journey through physical space.

Guiding us on this sojourn along this Dr Who-like continuum are two couples who move silently through each scene with exaggerated gestures, like live-action knitting pattern models. One pair are youthful, sporty, possibly newlyweds, who drive a go-gettingly with-it red mini. And the other are in late middle age, and very probably retired. Their vehicle, consequently, is a tubby, chrome-grilled, claret and cream saloon that exudes the safe, comfort over style practicality of a knobbly-buttoned cardigan from M&S or a good pair of wellies. Both voyage on, barely meeting another motorist. Pulling up on empty quaysides with little more than a tug of a handbrake, they saunter off to enjoy a run of maritime idylls and amply lubricated seafood lunches. With a legal drink driving limit and Barbara Castle’s breathalyzer lying, at this stage, some six years off, a spirit of (“Dash it all, we are on holiday, aren’t we Marjorie?”) one-more-for-the road prevails. A situation possibly only made worse by a clear division of gender roles that assigns the men, no matter how tight, the wheel and the women, the passivity of the passenger seat and, if lucky, an occasional chance to squint at the map.

An especially revealing incident occurs in a section on the perfect holiday in a sequence that is accompanied by images of a painter committing a picturesque bay to canvas. Lingering over every syllable, as only an actor who pronounces the word ‘off’ to rhyme with ‘wharf’ can, Rogers lists a trio of alliterative harbours – ‘Mouse Hole, Mullion, Megavissy’ – that he declares are ‘as pretty as a picture’. Just as we are absorbing this demonstrable truth, since a picture in situ is shown for our approval, he suddenly adds, less wistfully, and almost as if being handed a breaking news bulletin, ‘all joined by twenty minute lengths of motor road, no wonder artists flock to Cornwall.’

‘Cornwall’ and ‘motor road’, no matter how quaint the latter phrase now sounds, still strike a jarring note. Despite Shell oil’s sponsorship of guides, the implication that, in a sense, every budding Frank Bramley is a Mr Toad feels slightly distasteful somehow. Yet, this little detail provides the rest of this delightful fantasy with real verisimilitude. Here, in essence, is the mid-20th century dream of the car as the means of discovering the undiscovered for yourself, and the consequence-free, liberator of creative potential.

The British b-road, as anaemic a beast in comparison with the highways of America as, say Cliff Richard was to Elvis Presley in rock ‘n’ roll, might not inspire a kinetic rhapsody like On the Road. (Races to the coast on this side of the pond were more likely to stir up thoughts of Kenneth More and Larry Adler, than Jack Kerouac and Charlie Parker.) But with the wheel of an Austin Countryman, a Morris Traveller or possibly even a more resolutely pioneering Triumph Mayflower in your hands, a full pipe of shag clamped in your teeth, the wife at your side, a hamper full of spam in the boot and a tartan blanket and a spaniel on the backseat, the motorist of the early 1960s could feel at one with the wandering tinkers and painted wagons of an older Romantic tradition.

More films here

Caught by the River at Port Eliot 2014