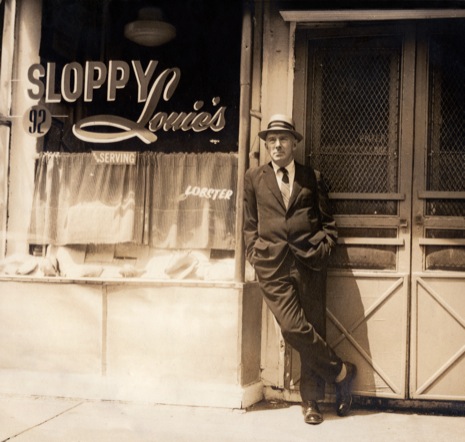

Photograph by Therese Mitchell

Man in Profile : Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker

by Thomas Kunkel

Random House, hardback, 344 pages

Reviewed by Andy Childs

Regular readers have already been introduced to the work of Joseph Mitchell via Ian Preece’s elegant appraisal of Mitchell’s writing that appeared here back in November 2012. If for some reason you missed or failed to respond to Ian’s fulsome recommendation and remain untouched by the great man’s oeuvre I would politely request that you first finish reading this review and then I would implore you to read Ian’s article again, then immerse yourself in Up In The Old Hotel (Mitchell’s collected works) and then invest in this excellent biography. A lot of reading I know. But it will surely be worth your time and afterwards you will hopefully have a full understanding of why Mitchell is widely regarded as one of the greatest journalists and commentators of the human condition that ever lived.

Man In Profile is a beautifully written and structured biography. Mr.Kunkel, who has previously published a book on New Yorker founding-editor Harold Ross, is clearly a Mitchell admirer and has used his copious interview material and access to archival papers to depict a life of personal dilemmas, good fortune, frequent depression, diligent and ground-breaking work in a trade at which he excelled, great sorrow at the way of the world (and especially the New York City he saw vanishing before his eyes) and ultimately, the frustration of a life’s work unfinished. Joseph Mitchell was born in July 1908 in Fairmont, N.Carolina, the eldest son of a successful cotton farmer who obviously expected him to take over the business one day. But Joe’s mother induced in him a love of books, he started to write, and when he realized that his chronic ineptitude at maths would surely prevent him running any sort of business, he made the difficult but inevitable decision to seek the life of a journalist, leave the family home and re-locate to New York in October 1929 where at age ten he’d previously visited with his father and declared “this is for me!”. His father was none too impressed – “Son,” he said, “is that the best you can do, sticking your nose into other people’s business?” Mitchell, naturally shy but determined, worked as a copy boy at the New York World, then as a reporter for the Herald Tribune, married journalist and photographer Therese Jacobsen in 1931, was fired from the Herald Tribune for famously defiling the editor’s office after a story alleging police corruption was taken from him and suppressed, signed on as a deckhand on a Russian-bound freighter, spent two weeks in Leningrad, landed a job at the World-Telegram when he arrived back in New York, and began to develop his inimitable style as a chronicler of New York life in the thirties.

A series of career-shaping interviews with anthropologist Franz Boas and a growing concern at the pace of change that was remorselessly eroding the New York he loved led Mitchell to pursue the task of recording the lives of the people who made that city what it was. Bored with the very notion of ‘celebrity journalism’, he wrote instead about Mazie the ticket-seller at the Venice Theatre who used to walk the streets of The Bowery by night dispensing cash to the needy. He wrote about the eccentric owner and clientele of McSorley’s Ale House. He described the life of Jane Barnell a bearded circus lady who, like him, left a North Carolina cotton farm for an uncertain and tempestuous existence in New York. He wrote about Mohawk steelworkers, Staten Island oystermen, and perhaps most famously, he immortalised the life of one Joe Gould – Harvard graduate, hustler, occasional drunk, scrounger, and supposed author of an ambitious work titled the Oral History Of Our Time. Mitchell chose outsiders, non-conformists, people who didn’t really fit the idea of what respectable New Yorkers should be but who nevertheless gave the city its character, its diversity, its very life. By this time Mitchell had been spotted and recruited by the New Yorker and was fast becoming their star writer, developing his lengthy profile pieces in an environment that gave him a degree of journalistic freedom and licence that he surely couldn’t have enjoyed anywhere else.

Indeed this latitude gave rise to a problem that perhaps for the only time in his career threatened his peerless reputation for scrupulousness. In January 1944 he published Old Mr.Flood, the story of a ninety-three year old “seafoodetarian” who frequents the Fulton Fish Market, a favourite source of inspiration for Mitchell. Two more Mr.Flood pieces followed but when the three essays were later collected together in a book Mitchell admitted that in fact Mr.Flood didn’t actually exist. He was a composite. An amalgam of various characters that Mitchell had come to know at the fish market with perhaps a dash of himself in the mix for good measure. This deliberate, if somewhat innocent, deception to some minds undermined the veracity and legitimacy of Mitchell’s profiles, while others – the majority thank goodness, including Harold Ross – excused this approach on the grounds that the great virtue of Mitchell’s impeccable style and his way of layering detail upon detail, real or imagined, to fully describe a character informed his writing with a depth and extra dimension that would have been lacking if he’d restrained himself from such artistic licence. When it subsequently emerged that other key characters in his collected ‘non-fiction’ such as King Cockeye Johnny (in King of the Gypsies) and Mr.Hunter (in Mr.Hunter’s Grave) were also partly fictional it should have come as no real surprise and Kunkel, himself deferring judgment on the ethics of such practice, leaves us to make up our own minds as to whether these profiles are in any way diminished as a result. I find it hard to imagine anyone who appreciates great writing thinking that they are.

Joe Gould of course was emphatically not a fictional character. There are photographs to prove it. But after Mitchell’s initial piece on Gould, entitled Professor Sea Gull, was published in 1942 it became painfully evident to the author that much of what Gould had imparted to Mitchell, including the existence of the Oral History, was fiction. And besides being a sham Gould had become a pest to Mitchell insinuating himself on the writer for more than a decade, so that Mitchell’s follow-up piece on Gould, Joe Gould’s Secret, published in September 1964, in turn exposed the crafty bum as a fraud but in a way that only the Southern gentleman that Joseph Mitchell remained all his life could have accommodated, also exonerated Gould from any damaging blame when it becomes apparent that he saw a great deal of himself in Gould. When asked why he found Gould so compelling, Mitchell replied, “Because he is me.”

To the extent that Gould apparently wrote mainly incomprehensible scraps of his Oral History and Mitchell wrote brief passages of autobiography but never published them (the New Yorker has since unearthed them in recent years) and that both of them indulged in the blurring of fact and fiction, the idea of Gould as doppelganger for Mitchell or vice versa remains an intriguing one and perhaps contributes tangentially to the unavoidable mystery of why, after the acclaimed Joe Gould’s Secret appeared in the New Yorker, Mitchell never published another word in that magazine nor, save for in the introduction to Up In The Old Hotel (1992), anywhere else for the rest of his life. This conundrum threatens, completely unfairly, to overshadow the enormous achievement of what he did write and Kunkel makes a valiant effort to reconcile this notorious case of so-called writer’s block by offering a cocktail of causes which kept interrupting his writing – the death of his father, his role as a grandfather, time spent minding the family farming business back in Fairmont, N.Carolina, the illness suffered by his devoted wife Therese and her death in 1980, his work on New York’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, and the grand idea he had to write a book about New York that was unfolding in his head and in snippets on paper in the form of autobiography.

But most likely, Kunkel concludes, the overriding reason for his absence in print was the fact that he had simply set himself such high standards and was such a perfectionist that nothing he wrote in the last thirty two years of his life was ever deemed good enough. He hadn’t stopped writing. He remained on the staff of the New Yorker all that time and he turned up for work most days (when he hadn’t decided instead to hang out at the Fulton Fish Market or McSorley’s Saloon) and his colleagues could hear the sound of his typing all day long. The fact that the New Yorker paid him a salary throughout these unproductive years and what’s more gave him a long-overdue payrise during this period is one of the more astounding stories associated with that unique and venerable institution. You’re either a huge fan of the New Yorker or it leaves you cold. I think it may be the best, probably the most important, and certainly the most consistently rewarding magazine ever. Why we in the UK have never managed to produce a publication to touch it is another of life’s mysteries.

Throughout the book Kunkel’s appraisal of Mitchell the writer is predictably warm and eulogistic and his portrayal of Mitchell the man is hardly less complimentary. Mitchell was well-liked, even loved amongst his many colleagues at the New Yorker. Kunkel’s Mitchell is an exacting character and mildly eccentric – always wore a suit and tie and a hat when he went out, dusted his large collection of books regularly and enjoyed vacuuming! He suffered periodic bouts of depression, liked a drink and was forever dissatisfied at what he earned at the New Yorker. In later life, when the writing occupied less of his time, he took to roaming the areas of New York that were being bulldozed away in the name of progress collecting seemingly mundane artifacts from condemned buildings – coat hooks, door knobs, nails, etc – taking them home, labelling them and filing them away in boxes secreted about the small apartment he lived in for over fifty years. It appears to be a poignant attempt to desperately safeguard a way of life and an era that his writing had already so eloquently preserved for all time.

There’s a good deal of talk these days about the idea of ‘place’ in what has emerged as a new hybrid of ‘nature writing’ that incorporates memoir, history and travel. All of these elements were present in Joseph Mitchell’s writing seventy years ago although he wrote primarily about human nature and his ‘place’ was New York City. He was indisputably a truly great writer and he now has the biography he has long deserved.

Thomas Kunkel talks about Joe Mitchell in this short film.

Andy Childs will be joining us at Port Eliot festival this Summer, for a unique event looking at the life and music of Nick Drake. More to come on this very soon.