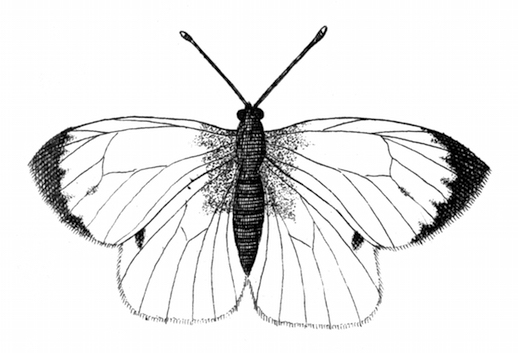

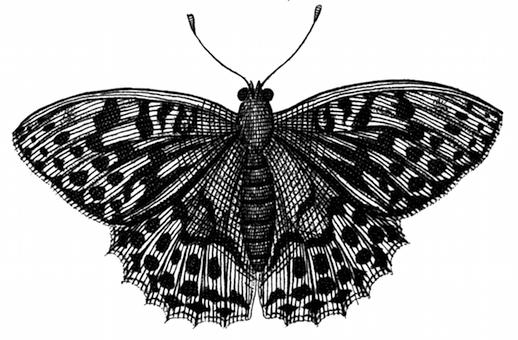

Illustrations taken from ‘Papilionum Britanniae Icones’ by James Petiver (1717) and ‘An Illustrated Natural History of British Butterflies’ by Edward Newman (1871)

Words and photographs: Sue Brooks

Arnside Knott, overlooking Morecambe Bay in early July this year. A light southwesterly wind, sunshine through thin cloud. I made myself walk slowly. I let my eyes scan in a casual way and thought hard about deferred gratification. There is no better means of intensifying the desire.

I stood still in a clearing with bracken, brambles and thistles sparse enough for violets to grow in the leaf litter. Mature oaks, holly and elder close by. I waited and they came. Small Pearl Bordered Fritillaries – golden-winged butterflies scudding from nowhere to take nectar from the thistle flowers. Nabokov’s words in my mind, as always at such moments – the highest enjoyment of timelessness .….. is when I stand among rare butterflies and their food plants.

Some time later I thought I was getting closer to the part of Arnside favoured by the High Brown Fritillary – the most endangered U.K. butterfly. A south-facing slope with short grasses and a rich variety of wild flowers. It felt right. However – apart from declining by 80% in the last 30 years, the High Brown is almost impossible to distinguish from the more common Dark Green Fritillary without seeing the diagnostic pattern on the underwings. On the upperwings, the only difference is the third spot from the outer edge of the forewing which is slightly indented, rather than in a line on the Dark Green. Not once that afternoon did a single large golden fritillary settle with closed wings. I strained through the binoculars for the third spot from the edge, seeking gratification. To hell with deferment. Was that an indentation? Indisputably.

I came late to the love of butterflies. They did not enter my imagination until I was reading Nabokov obsessively in my late twenties. Like him, every butterfly enthusiast I have encountered since, was entranced as a child, mostly little boys. It didn’t seem to happen to girls. The autobiography Speak, Memory was my favourite, especially Chapter 6 where he describes in exquisitely elegant and sensuous prose his passionate falling in love with the lepidoptera on the family estate near St Petersburg. It imprinted deeply and years later, in some magical way which felt natural and inevitable, the doors opened, and I walked into the world that had been silent and sealed for four decades.

A Hummingbird Hawk Moth was the door keeper; appearing in my garden one warm afternoon in 2011, dipping its tongue deep into the corolla of a honeysuckle flower, allowing a long timeless moment with the olive and pink body almost stationary inside a vibrating halo. It is said to be the bringer of good fortune.

Patrick Barkham’s The Butterfly Isles, published the same year, was my guide. I followed his quest to see all 59 species of butterfly in the UK, and began to discover some of them myself as I was walking the dog. Most notably the Wood White, described by Patrick as rare, but in the mysterious way in which things were developing, the only white butterfly along the familiar daily track. Two rested on a bramble leaf facing each other. One seemed to be stroking the other with delicate movements of the proboscis and antennae. I moved closer and could see the black and white stripes and the shiny tips. The white bodies, with ghostly pale folded wings, were quite still. There was only the hypnotic waving of the antennae. I imagined if butterflies could close their eyes, they would be closed. The courtship ritual of the Wood White, according to the Field Guide. I have never seen it since. I am deeply grateful to Patrick for this initiation. Apart from Nabokov, he has been the only writer who describes how it feels to be in the presence of butterflies and their food plants, how each of the 59 has its own unique quality which becomes evident over time – their personality, for want of a better word – jizz in the bird world.

2015 has been an outstanding year in this respect. Two new books about butterfly enchantment: Matthew Oates’ In Pursuit of Butterflies: A 50 Year Affair And Peter Marren’s Rainbow Dust: Three Centuries Of Delight In British Butterflies. Both have been wonderfully enriching.

There is no doubt that Matthew Oates has been totally and gloriously in love since the age of 10. On Sunday May 19th 1968, he ran the two and a half miles from his boarding school in W. Sussex to Marlpost Woods, entered the wood at the zenith of Spring and crossed rapturously into a new dimension. There were in those halcyon days, colonies of what are now rare butterflies in the woods of the southern counties of the U.K. His diaries recorded every detail of the love affair, including the emotional highs and lows. He was given a full-time occupation, a passion, a lifetime’s happiness, and perhaps most important of all, the gift of patience. Patience which enabled him over weeks, months and years of watching and waiting, Jonathan Agnew’s Test Match Special voice in the ear-phones, to gather the data which is crucial for good conservation. That Brimstones prefer to lay their eggs on young buckthorn rather than mature trees, for example, or Scotch Argus females favour short grasses, no more than 8cm tall, in May and June. There is a wealth of information here about the finer aspects of butterfly ecology, and so much more which remains unknown. Even after 50 years of study, their ability to surprise us seems infinite.

The butterfly Gods smiled on their loyal servant, giving him access to some of the most elusive and tantalising species, especially the Purple Emperor on which Matthew Oates has become one of the foremost authorities. The long running website thepurpleempire.com provides information about sightings throughout the season. He has never ceased in his quest for ap Iola, the rare black form of the Purple Emperor – once I finally encounter this miraculous chimera, I will give up butterflying. I trust it will remain the Holy Grail of his dreams, forever unattainable.

Male Purple Emperor on fox scat, Fermyn Woods

Male Purple Emperor on fox scat, Fermyn Woods

Peter Marren’s book is filled with people as well as butterflies. People whose lives, like mine, were changed by butterflies. Exotic, fascinating people like Lord Rothschild – who ironically included ap Iola in his vast collection, now residing in the Darwin Centre at the Natural History Museum – Elinor Glanville, and the unforgettable Edward Bagwell Purefoy who first unravelled the mysterious life cycle of the Large Blue. Also the history of the names of butterflies, both common and Latin. To a beginner, the names are part of the allure: the Silver Studded Blue, the Brown Argus, Green Hairstreak, Silver Washed Fritillary, the Duke of Burgundy. The Latin names even more so. 28 of the 59 British butterflies are named after characters in Greek mythology. Nabokov’s favourite butterfly, the Red Admiral, is given a whole chapter. I have looked hard in my garden for the numbers 1881, said to be distinguishable on the hind wings after vast numbers of Red Admirals were seen in northern Russia at the time of the assassination of Tsar Alexander 11 in that year. It is clearer on some butterflies than others. I haven’t seen it yet, but it’s all rich food for the imagination.

Both authors have strong views on butterfly conservation. Peter Marren, for example: Even conservation charities are starting to recognise that nature reserves – butterfly ghettoes – are almost a council of despair, a procedural blind alley offering short-term expediency rather than a long-term answer…… these are deep waters. Deep waters indeed. But not as deep or as long lasting as our human infatuation with these mysteriously beautiful creatures. There must be love in order to feel the pain of potential loss – an England without Fritillaries or Adonis Blues. Perhaps next year I’ll learn to tell a High Brown Fritillary from a Dark Green Fritillary ON THE WING ( Matthew Oates can do this ) or see the gold spangled pupa of the Red Admiral, or camp in Compton Bay on the Isle of Wight for the emergence of Glanville Fritillaries in early June. Plenty of time for deferred gratification. I’ll keep you posted.

In Pursuit of Butterflies: A Fifty-year Affair by Matthew Oates is available here

Rainbow Dust: Three Centuries of Delight in British Butterflies by Peter Marren is available here