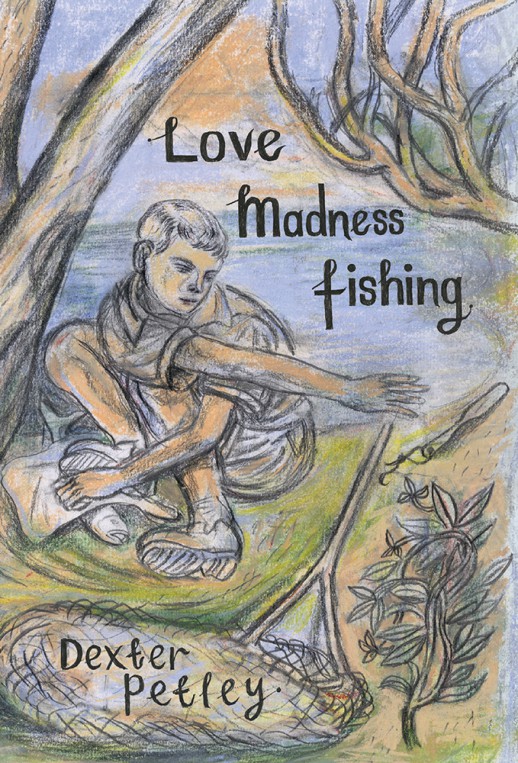

An extract From Love Madness Fishing, our Book of the Month for April. Published by Little Toller / Caught by the River. Out April 12th and available to preorder now.

An extract From Love Madness Fishing, our Book of the Month for April. Published by Little Toller / Caught by the River. Out April 12th and available to preorder now.

Words: Dexter Petley

Nineteen seventy-one was the summer of puppy love. The curtains fell from my eyes and I was blinded by sight. Under Sarah’s guidance, and the Ordinance Survey map she always carried, Hawkhurst became transfigured, from a kind of open borstal of the over-familiar, into a new world of rustic vocabulary. Places once designated for a laugh were now traversed by bridal paths where romantic excursions held overtones of local history. Streams and ponds, no longer targets for floats and worms, became the tapestry images in Sarah’s medieval landscapes, aesthetic bowers where she taught me nature’s poetics. I became a cultural novice. How to feel the rain, watch a tree, listen to the words of birds. The fishing rods, for by now I owned six, became interred in shame, in the outhouse cemetery, with the cannon-ball, Mac’s tools and the dog’s box.

A novice is always disturbed by immensity. The sombre notes, the undertones, were in Sarah’s poetry. It wasn’t an ordinary sadness. My early sense of being locked out of her poetry intellectually eased, through reading the collections she leant me. Instead, into that disturbance, came a fear that I would lose her to the very thing driving these precocious and brilliant poems. We saw each other every day, learned to kiss and walk miles arm in arm without tripping over our gowns and tie-dyed fancy dress, but all the time our happiness didn’t seem as strong as the sadness, or gloom, in her poems. Then one morning she took me off on a short walk over the Lawns behind Theobald’s Pond. She had something to tell me, something, she said, which would make me despise her. I feared that maybe I wasn’t the first to have put my hand up her smock, but no, it was an invisible hand which had been there first. I had depression, she said.

Perhaps depression wasn’t a poetic enough word. Sarah over-estimated how far I’d got with poetry if she thought I’d despise her for it. It was cold fear went through me instead. Until then, my progress had depended upon emulation. My fear was losing her to someone else, not invisibility. Ignorance runs so much deeper than wisdom. Everything she said to me was still new, previously unknown, and now this, another truth to diagnose. I had never been depressed for a minute of my sixteen years. But Sarah, at the age of fourteen, had spent several months in Bethlem Royal, a notorious mental hospital. The rumours had been true. They had to send her away. She made it sound like a great public school for sensitive genius, where great poets and artists had suffered for their art. There, she’d read Sylvia Plath and forged her solidarity with fellow ‘lunatics’ Louis Wain, John Clare, Christopher Smart, Richard Dadd, Ezra Pound, Robert Lowell. She’d watched a girl set light to herself on the hospital steps. She took walks with a printmaker who starved herself to death. Sarah made the knowledge of such things seem as essential to a poet as the first trout is to a fisherman.

The correct response eluded me. I attempted something like: that’s all right, I’ve been depressed too. She walked off shouting. No, you don’t understand. I mean real depression, suicidal depression.

Even the intellectual is manual labour for a working-class youth. By September the worm had barely turned, a maggot hardly hatched. I was a poet, but I was Sarah’s cultural slave, doggerel in the manger, still confused by this insistence on melancholy which love and poetry seemed to demand of us. Sarah began her last year at TWIGGS, in the fifth form. I enrolled at West Kent College of Further Education in Tonbridge. I’d left Swattenden with more roach over the pound mark than CSEs. O levels were for the elite, not the done thing at Swattenden, which had ceased educating anyway, flattened by the rise of the comprehensive. I’d been its last ever expulsee.

Sarah had procured the West Kent prospectus for me. She was enrolling herself the following year for her A levels, those two-pound roach of the mind. I had a year to get the entry requirement, two O levels. There was no question of her going to study poetry without me. My present course was flatteringly known as pre-diploma business studies. Five crammed O levels: economic history, accounts, the principles of English law, statistics and British Constitution. Lectures were in the Territorial Army drill hall. Access was through the garage bay where armoured vehicles were left unguarded. The rooms were cramped and dark. The lecturers were shabby, depressed men with bleak medical futures. Hernia men, goitres and stomach trusses already.

Fishing had been so thoroughly extinguished. Instead, I’d filled two exercise books with upside down floats; concrete poems which sunk to the bottom with the corpses of childhood, First World War poems where Tommy rides a ghost train in Flanders, derivative boggeral and polluted intention, the crude approximations of anything I read. The country was a part-time influence, the silent end of a day. Between 8.30 a.m. and 6.00 p.m., the towns were my pools and streams of knowledge. Such unfished territories, Tunbridge Wells and Tonbridge public libraries, teeming with books in unimaginable quantities. These I devoured in a poetry binge, the risked obesity of the autodidact. I read Ezra Pound’s Cantos in accounts, while sweaty Simms in his pink nylon shirt explained the new giro cheque system; I read Sylvia Plath in statistics and Ted Hughes in Brit Con, under the desk or behind my green fishing haversack, now the repository of ring binders and mouldy text books. It’s a feature of giving up fishing that you find yourself, in your neutral state, near better fishing waters than you have ever known. Tonbridge had the Medway. I saw it daily, wide, brown and alien. I felt sorry for the men who angled there. My glance was an unpleasant one. They hadn’t read Pound or Eliot. They weren’t going out with Sarah Jeffery. They might have said away with you then, you have to be worthy of the waters you fish.

Love Madness Fishing is available to buy from the Caught by the River shop, priced £15.00

Dexter will be making a rare visit to the UK this summer to be our guest at Port Eliot Festival and Caught by the River Thames (Saturday 6 August). At both of these events Dexter will be talking with his Letters From Arcadia correspondent John Andrews, undoubtedly a gig of the year for long term readers of this site and all lovers of country/nature writing.