Illustration taken from Issue 2 of Country Bizarre magazine

Illustration taken from Issue 2 of Country Bizarre magazine

Foxes Unearthed: A Story of Love and Loathing in Modern Britain by Lucy Jones

(Elliott & Thompson, 256 pages, hardback. Out now and available here in the Caught by the River shop.)

Review by Diva Harris

As I walk home from work at dusk, I am on the lookout for a fox. I figure that it would make the perfect anecdotal opener to a review of a book about foxes.

I live next door to one of London’s largest areas of common, and to a secondary school whose detainees, upon daily release, leave a chicken-box-strewn pavement in their hasty wake. What with the abundant scraps and my numerous past encounters with foxes, I’m under the illusion that another is not only possible, but also likely.

A few pages into Foxes Unearthed, we find Lucy Jones in similar circumstances. She is camouflage-clad as she takes to Walthamstow Marshes, armed with a copy of Martin Hemmington’s Fox Watching and a pair of binoculars. Whilst this blows my half-arsed attempt at fox pursuit out of the water, she and I find ourselves in the same predicament: ‘As it turns out, foxes can be elusive creatures when you’re in active pursuit, and my search proved frustratingly fruitless.’

Perhaps we have both been outsmarted. Cunning is, after all, what foxes are best known for – a perception which may be millennia old, as Jones tells us in this thorough and captivating history of our relationship with the fox.

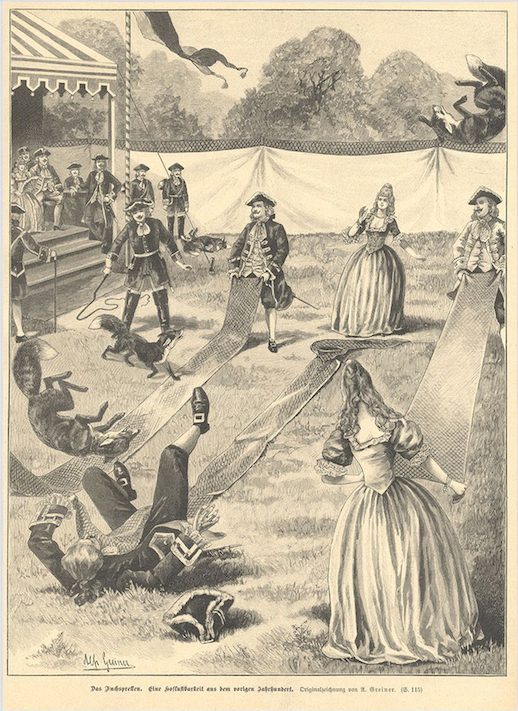

Unfortunately for poor old vulpes vulpes, said intelligence doesn’t seem to have won the species much respect over the years. It is both fascinating and horrifying to learn of ‘fox tossing’, a pastime supposedly beloved of aristocratic couples in 17th and 18th-century Europe. The game ‘took place in squares of lawn or courtyard and involved tossing the animal as high as possible from strips of material taught as a tightrope.’ Usually resulting in the fox’s death, Jones notes that ‘a good effort was tossing the fox 24 feet high into the air.’ As though the pursuit were not already preposterous enough, there is the added detail that ‘occasionally the sport would take place during a masquerade ball when the players as well as the vulpine participants would be dressed up in masks and costumes.’

Similarly absurd is the Tudors’ use of fox body parts in medicinal practice – and not just any parts, but the penis, which ‘adults were encouraged to tie around their aching heads to relieve the pain of a migraine’, and the testicles, ‘tied around the neck of a child suffering from toothache in what might be considered the least charming necklace in British history.’ These deadpan asides, coupled with the numerous and varied fox facts peppered throughout the book (Philip Schofield once ate fox meat live on air and people weren’t happy about it; you can buy fox piss online for £35 per hundred millilitres, to name but two) lend comic relief to what is at times a dispiriting read. We have, historically, subjected the fox to much persecution – and indeed we continue to do so.

Engraving of German aristocrats engaged in fox tossing, or ‘Fuchsprellen’ c. 1895

Engraving of German aristocrats engaged in fox tossing, or ‘Fuchsprellen’ c. 1895

A lengthy portion of the book focuses on fox hunting, providing a platform for both its advocates and critics as well as detailing variations of the sport and the numerous loopholes via which people are still able to participate in it. Given the touchiness surrounding the tradition’s tie-up with politics and social stratification, it is to Jones’s credit that Foxes Unearthed does not come down strongly on either side of this contentious debate. Instead, it questions and philosophises, continually challenging the reader’s preconceptions, whatever those may be. A left-leaning, vehemently anti-hunting vegetarian of 15 years, I was surprised to find myself newly empathetic towards hunt supporters in light of some of Jones’s arguments in their defence. Never before had I considered, for example, that as a city-dweller I have no stake in a pursuit which is ‘part of the rural economy and cultural fabric, embedded in rural identity.’ Neither had I considered that the process might be more widely supported were it a means to a culinary end, that it is ‘the pursuit of an inedible animal that makes the practice an invented cultural pursuit, and not a natural one in the way, for example, hunting deer or boar for dinner would be.’ Compelling too is the repositioning of fox hunting within the context of war: Jones proposes that soldiers returning from WWII may have been ‘so used to a high level of adrenal intensity that they fed it through the sport of fox hunting’, acknowledging that perhaps men returning from war ‘needed’ hunting in a way that she – and anyone else unacquainted with a war zone – could never truly understand.

Of course, foxes are frequently killed outside of organised hunts, and legally so: by farmers and pest controllers, largely. Justifications for this include the argument that they pose a threat to livestock or wildlife. This, like hunting, is a contentious topic. It also throws up the book’s vital message, nicely summarised by celebrity fox friend Brian May when he drops this truth-bomb:

The real reason for the decline of birds and other wild creatures can always be traced to human intervention. Lapwings and curlews coexisted with foxes for hundreds of years before their habitat was compromised by human activity. We have to look to our own behaviour to discover why the numbers have declined. The natural extinction rate of species on Earth has been recently estimated to have accelerated a hundredfold since Man became numerous as a species. So clearly the problem is us, but finding the solution is not so easy, especially in a culture that prioritises economic growth above any other consideration.

And there we have it, Foxes Unearthed’s uncomfortable subtext. Foxes are not inherently bad, but it has been convenient for us to portray them as such for thousands of years. That we are compelled to eradicate ‘anything that might challenge manmade harmony’ is terrifying, and, argues Jones, ‘damaging to both human-animal relations, and to the wider environment’.

It is satisfying that a book which conveys an uncomplicated delight in the natural world – the fungi ‘with wonderful lyrical names: Soapy Knight, Plums and Custard, Purple Jellydisc, Hairy Earthtongue, Black Witches’ Butter…’ ; the ‘pure, chemical thrill’ Jones experiences when she encounters a fox – simultaneously sends such a sobering message.

As I amble home from work one evening later in the week, I get to experience that thrill when a flash of russet catches me off guard. And I remember Lucy Jones’s powerful words: ‘It must be possible to reorganise our priorities to safeguard the natural world.’ Here’s hoping.

Read an extract from ‘Foxes Unearthed’ here. Lucy Jones talks foxes with Chris Packham on tonight’s Springwatch: Unsprung (6.30 pm, BBC2).