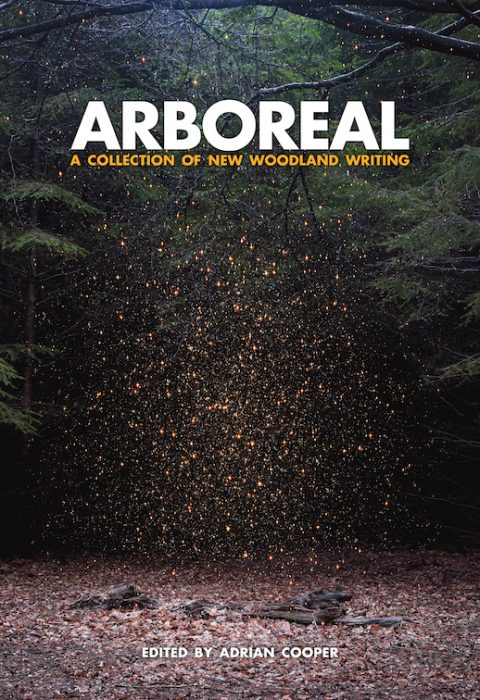

Arboreal is a new title from Little Toller Books. Bringing together some of the finest and best-known names in contemporary writing, this new anthology explores the many strands of what woodlands mean to us.

Contributors include Richard Mabey, Germaine Greer, Ali Smith, Simon Armitage, George Peterken, Paul Kingsnorth, Paul Evans, Richard Skelton, Tobias Jones, Jay Griffiths, Peter Marren, Madeleine Bunting, Kathleen Jamie, William Boyd, Tim Dee and Evie Wyld.

Here follows the introduction, written by the editor, Adrian Cooper. Pre-order a copy of the book here.

*

South Mead Coppice, Dorset

I felt at odds queuing at the post office, back in the summer of 2013, holding a cardboard box with Oliver Rackham’s walking boots inside. By the time it was my turn to plant the package on the counter – First class, please, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College – I wasn’t sure whether the book we were developing together, what later became The Ash Tree, was quite working. He’d been visiting us to deliver photographs and to discuss the first draft, and after lunch, while the taxi bustled Oliver away to the train station in his sandals, I started to feel uncertain about his approach to a particular chapter on the cultural history of ash, which I’d hoped would explore the artists and writers who’d responded to the nature of the tree. That’s when I noticed his boots were left behind in the office, and my thoughts turned to the miles of ground they’d covered (in Dorset, Cambridge, Crete, Texas), the man and books they’d supported.

The works I’d most enjoyed publishing, until then, were illustrated with engravings, line drawings, paintings or photographs which, to my mind, expressed the essence of the book. Yet, in the early drafts of The Ash Tree, I felt that my task was to coax Oliver towards John Constable’s Hampstead sketches, David Nash’s living-ash sculptures at Cae’n-y-Coed, or John Clare’s ‘hollow ash’, Edward Thomas’ Llwyn Onn (‘Ash Grove’), and even Yggdrasil, the world tree, of Poetic Edda. There were plenty of photographs taken by Oliver himself over decades of research, hand-picked from his collection. But must every image in the book illustrate a point raised in the text?

Plucking up courage, I confronted him. His response was to email a table of: ‘The more commonly-mentioned trees in the works of literary writers’, which compared how many times different tree species – oak, pine, yew, willow, hazel, beech, elm, poplar, cedar, cypress, holly, birch, lime – were mentioned in literary works, first by Shakespeare (one ash tree) then Wordsworth (thirteen ash trees), Tennyson (nine ash trees) and Yeats (sixteen ash trees). While this was not quite what I had in mind, it was something to build on, and when The Ash Tree went to press a year later, most of the suggestions I’d lobbied for were included. But this was no victory of publisher’s will or taste; in the finished book, the sections on ‘literary ash’ and ‘ash in art’ occupy only four pages, in which Oliver insists on reminding the reader: ‘No painting, drawing or photograph of a big tree can be naturalistic.’

On the surface, this is an obvious thing to say – put to mind a mature ash, with those complexities of branch and leaf, every wooded angle rich with the stories of the local environment which nurtured its growth. So yes, trees are difficult to draw. A complete woodland, therefore, will never be seen, even with drones now able to map every tree. But as with the many things he wrote, the simplicity of the prose quietly went to work challenging my preconceptions, even my feelings of attachment to particular trees or woods, changing fundamentally the way I understood landscape.

Knowingly or not, Oliver was teaching me to think about woodlands as dynamic places, living societies that support other living societies of plants and mammals, birds and micro-organisms. Of course, this is not to say that we shouldn’t appreciate trees and woods, forming our own bonds through walking, making art, poetry, music, new architecture or social projects. It does mean, however, that what we understand about trees and woods will never form a complete picture.

Trees, like all wildlife, are autonomous, outside of our understanding and control. We are certainly neighbours, but not always very good ones. Human intervention in any landscape, like the management of woodland, can enrich both human communities and wildlife habitats. But we don’t have to look far from our own doorsteps to discover these interventions are driven by human needs, and do not absorb the nuance that Oliver argued for. Neither do we need to look very far back over our shoulder, into the past, to be reminded that almost half of the ancient woodland in the British Isles was either felled or poisoned between 1933 and 1983, the work of policy-makers and landowners reacting to ideas and needs of the time. As is true of anything in nature, trees aren’t just the subject-matter of poets and artists, nor just a utility for burning or building, and they do not grow for ecologists to write about and so publishers have paper to print on.

On the day of his death, 12 February 2015, those boots I’d posted to him in Cambridge came back to mind. I was no longer thinking about the ground they must have walked. Instead, I wondered whether anybody could possibly fill them.

This book seeded while I stood in that post office queue, and took delicate root in the weeks after his death. But it is not an attempt to fill Oliver’s boots, and nor does it continue anything particular about his work or life. (I also doubt that he would have been pleased to know of such a book, written in tribute: his own voice was distinct and clear enough.) Yet the very first page of Arboreal bears his name because the book is driven by a hope that, without Oliver Rackham, there will continue to be people who speak out for trees and woods; interpreters of the natural world who remind us of the complexities and demand sensitivity when we do intervene, as we inevitably do, leaving our marks on the land.

This hope has been nourished into growth by the pioneering work that Sue Clifford and Angela King began with Common Ground’s band of collaborators back in 1986 (I was a ten-year-old, not even a resident of the UK), when the project ‘Trees, Woods and the Green Man’ began to explore the natural and cultural value of trees, with pamphlets, plays, books, newspapers and art exhibitions. This is why a small selection of the work of those collaborators – Andy Goldsworthy’s sculpture, James Ravilious’ photography, David Nash’s charcoal drawings, Kathleen Basford’s Green Man archive – appear

through the book, acting as unannounced clearings amongst the words. They also tell their own story, illustrating the rich and enduring purpose of Common Ground’s work, which, over three decades, has consistently challenged the growing estrangement between people and nature with imagination and activism.

Today, there is certainly a story of estrangement to confront in our relationship with woodlands. A century ago, along with hedgerows and orchards, woods began drifting away from parish life, becoming less essential for heat, food and shelter. The arrival of cheap coal, imports of Scandinavian timber, and improved transport across the British Isles, followed by the felling and ploughing-up of ancient woods during the First World War, meant that by the 1920s a majority of small, deciduous woods were becoming redundant to community life. Woodland culture began to vanish – the coppice and underwood crafts, the charcoalmakers, bodgers, the wheelwrights, boat-builders and cloth-dyers, all of which have their techniques and traditions in pre-history.

Yet here, in the twenty-first century, this distance from our day-today lives can seem slight. Think back to October 2010: the Conservative Government announced a consultation to ‘reform the public forestry estate’, the ‘Big Society’ shift away from state ownership and ‘a greater role for private and civil society partners’. The idea, a ‘forest sell-off ’ as the Guardian and The Telegraph had it, met with a great upswell of rejection, an outcry so wide and resounding that just four months later the proposal was abandoned. A similar public reaction followed the great Storm of 1987, when, after the apparent loss of 15 million trees overnight, the public mourning did not stop the fallen or tilted trees – assumed dangerous or dead – being chopped up rather then left alone to keep living.

This combination of estrangement and affection is curious. On the one hand, we are able to stop a government in its tracks when they ‘sell off’ something that we feel attached to. On the other, we have spent over a century spending less time being in the woods, and as a consequence surely think less about what they are for and what they mean. The majority of us do not own woodlands nor earn our living by them, yet it seems that the trees and the woods still inhabit us. I have several in me. There are memory forests, imagined or barely remembered places, and there are others which are living and very much alive, like the beech woodland in the Chilterns with its ancient boundaries still visible as humps in the shade, and a swilly hole that even now I imagine will swallow me up. There is also a plantation of Sitka spruce, near the first place I rented in rural England, where the quality of light never seemed to change. That veil of blue-browns, except on autumn mornings when sunlight smoked through the high branches, translated as halos of white on the needle floor, and the snowdrops announced themselves as a little miracle resisting the mono-culture. Today, there is South Mead, a sloping hazel coppice on our doorstep, unused for at least fifty years, now pocked with setts, dens and burrows. It’s a narrow corridor where our children have discovered for themselves that time warps in woodland, becomes elasticated, lasting much longer than out in open ground. There are probably more woods, too, if I go further back to count places like the Nairobi Arboretum near my boyhood home, with its gangs of vervet monkeys that dismantled the suburban hush with claws on corrugated rooftops.

We may be able to move through woodland, or climb up the branches of a particular tree, but it is the woods and trees which move into us, become entangled in our memories, taking root in our language. This is why the stories in this collection are personal and located, most often in real, living woodlands named on maps, although some are metaphorical places, memory forests, even fictitious. My hope is that the variety of voices gathered here, the writers, woodland ecologists, architects, artists, foresters and teachers, all of whom have harvested their own experience in the woods, combine to speak with the complexity and nuance that Oliver Rackham would have appreciated. I also hope this breadth argues that trees and woods need not be exclusive, and that we should be widening access to some of the 47 per cent of woodlands that, according to the Forestry Commission, ‘remain unmanaged or under-managed . . . in private ownership’ (about 1.5 million hectares of the United Kingdom). This situation has improved since the creation of the Forestry Commission in 1919, when access to woods first started to widen. More recently, the promises of the Localism Act 2011 should also give communities the opportunity to buy ‘assets of community value’, making it possible for woodlands to be looked after by small groups of people or local organisations, rather than individual landowners or big companies.

There is still much to learn about how to improve access for all, but community woodlands and social forestry initiatives are now spreading across England, and have been longer-established in Scotland and Wales. These woodland groups vary from place to place, from wood to wood, but generally begin with people getting together to buy, lease or borrow woodland from local landowners, wildlife trusts or the Forestry Commission. And this wider variety of people, now able to access and

manage local woods for themselves, has meant the growth of new ideas about woodland practice. Wildlife conservation, wood fuel and timber for joinery are all still good reasons to manage woods, but a shift in who manages them also means a shift in what woods are managed for. Community healthcare projects, apprenticeships, firewood allotments, artistic practice, architectural education and Forest Schools are appearing all over the UK, creating new community spaces which, with sensitive and meaningful management, are bringing woodlands closer to the everyday lives of more people.

Imagination will always be one of the most powerful tools we have to counter estrangement, in the relationships we have with each other and the natural world. But so too is proximity. If we have contact with woods, the trees inhabit us. This transformative power is essential, and will continue to be so, no matter where you come from in the British Isles, whether you are rich or poor, young or old, and so long as there are hedges, spinneys, groves, thickets, hursts, holts and copses growing into the earth and towards the sun. Trees and woods absorb our restless activities, capture our imaginations, not to mention our carbon dioxide, and all the while grow and fall, shake off leaves and regrow them again, living autonomous lives as they soak into us, becoming valuable characters in the places we live, sustaining and enriching nearby life, becoming part of who we are.

*

Keep an eye out for more on Arboreal next month – it’s our Book of the Month for November.