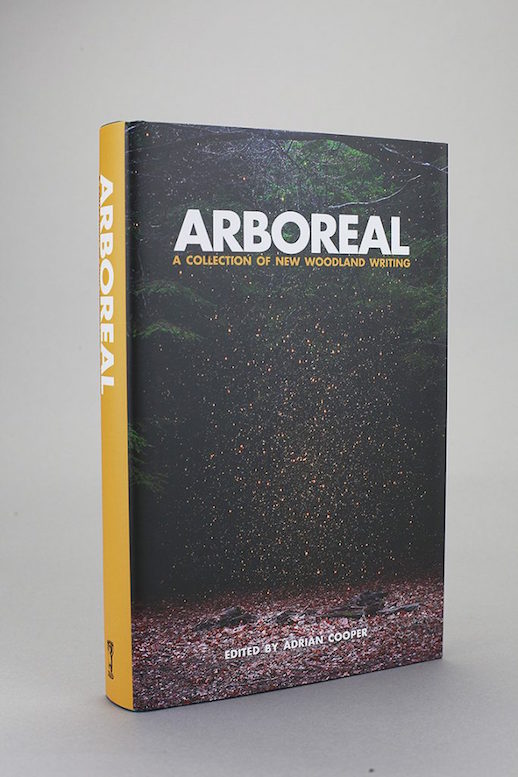

An extract from Arboreal: A Collection of New Woodland Writing, our Book of the Month for November. Published by Little Toller. Out now and available to buy here in the Caught by the River shop.

An extract from Arboreal: A Collection of New Woodland Writing, our Book of the Month for November. Published by Little Toller. Out now and available to buy here in the Caught by the River shop.

Forest Fear

Wood of Cree, Dumfries and Galloway

by Sara Maitland

The Cree is a small river that drains off the western side of the Galloway Hills; it is joined by the Water of Minnoch and most of its relatively short course runs through Dumfries and Galloway. Below Newton Stewart the land flattens out into merse (or more locally ‘inks’) – tidal grass flats, famously home to overwintering geese – and the river officially ends at Creetown where it flows into Wigtown Bay and thence into the Solway. The valley of the Cree above Newton Stewart is to me one of the prettiest places in Britain (not beautiful or sublime or spectacular, but very, very pretty). Green and sweet and sheltered, climbing steadily into wilder country with the profile of the big hills above. On the east bank of the river, half a dozen or so miles above Newton Stewart and hanging on to the steep valley sides is Wood of Cree, the largest extent of ancient woodland in southern Scotland. A series of burns flow down from the high moor, cutting through the wood – fast, always noisy, rocks and water, white with foam and golden brown with peat; there are several impressive waterfalls.

Wood of Cree delivers almost everything you would anticipate from ancient northern oakwood – oak trees of course and birch and rowan and hazel and crab apple; erratic boulders shoved into position by glaciers as well as the rocks pushed down more recently by the burns; an understorey carpeted with thick green mosses and draped with honeysuckle and lichens; and in season bluebells of course, but also some of the most flourishing, delicate, yellow cow wheat I have ever encountered.

But, at the same time, and like every other bit of ancient woodland, Wood of Cree is not like every other bit of ancient woodland because it, like them, has a long and complex relationship with people. Wood of Cree has been heavily managed, mainly for oak coppice, since at least the seventeenth century; probably because of its steepness very few oaks were grown on as maidens for timber – clear-felling was the traditional method of managing this wood. In the early 1920s it was clear-felled for the last time; but it was never grubbed up or replanted extensively with larch or spruce. This means that almost all the oak trees are the same height and age; but growing on much older roots; many of them are multi-trunked and they are very thin and tall – and close together, except where granite outcrops prevent them growing at all. This gives the place a rather different atmosphere from more usual oakwood, and in particular it feels more fairy-tale than ancient; more frolicsome than awe-inspiring. It also has an unusual ‘soundscape’; not only is the sound of running water very loud and coming from all directions, but in addition the tall, thin trees are very ‘creaky’, even moaning.

Wood of Cree is now an RSPB reserve. Fairly obviously this is because it has a particularly rich avian taxa including a healthy summer breeding population of pied flycatchers – along with many other delights, and is blessed by an extraordinary, notable dawn chorus. The point about this here is that it all means it is still managed woodland; the paths are good, there are car parks and the whole place is littered with nesting boxes, interpretation boards, signposts and convenient benches. Although it is very pretty, it is not actually very wild. It is not a place where I anticipate feeling overwhelmed by deep fear. But I was.

Last January I went for a walk in Wood of Cree. The Cree, which only a couple of weeks before had broken through the flood wall in Newton Stewart and inundated the High Street, was still huge and fast and dark and threatening and the burns coming down were roaring more ferociously than ever. But the sun, for once, at last, was shining and, although it was muddy underfoot, it seemed sweet and agreeable to be out and the winter wood appeared gentle and welcoming.

I have a small golden-coloured dog – her vet who loves her describes her as a ‘stretched border terrier’: border-terrier size but all shaggy and elongated. She has an exceptionally joyous and ebullient character; nervy, timorous or servile are not words that come to mind in describing her! Like many terriers she likes to be The Leader and, when not distracted by wonderful woodland smells after too little walking in the previous weeks, she barges past me and heads out up the path. I follow her, wondering somewhat at the signs of preposterously early spring – there are green leaves on the honeysuckle and the hazel catkins are stretching themselves out and down, already turning from purple nubs towards golden rain. The moss seems denser and more luxuriously green than I have ever seen it, ramping over the rocks and up the tree trunks. The wind drops abruptly. And I hear her howl, above the crashing sound of the burns; a long howl followed by a strange, loud whimper. I start to run up the path, but it is very muddy and steep and I am unfit from the long spell of wet-confining winter. I stumble. Suddenly, she comes hurtling down the slope, throws herself against my legs and I can feel that she is trembling. I bend down to her and realise she is half wild with fear.

And then I am too. I am consumed, abruptly, breathtakingly, totally, by terror. Some atavistic bitter flavour that I cannot identify rises in the back of my throat. I am unable to move – this is something way beyond the adrenalin rush of ‘flight or fight’; this is something very dark and primitive; above the sound of running water I can feel my heart thumping; the taste of the fear is itself fearful.

It does not last long, moments rather than minutes. Then the dog relaxes, looks at me almost slyly, shakes herself vigorously and turns and trots off up the path again. I straighten up; wilfully unknot all my clenched muscles with a sort of shudder rather closely akin to her shaking; take a deep breath. Think, ‘What was that?’

And indeed, what was it?

I have felt it before, this forest fear. Older sections of the great Caledonian Forest have produced a very similar sensation, with a background awareness of the ghosts of long-gone wolves; and coming down from a long, high hill walk, through plantation forestry and realising that it will be dark before I reach my car has had the same effect. I have never (I am glad to say) been seriously lost in the woods, but I would take all possible care not to be. I have however been frightened on numerous occasions – once on the very final cusp of dusk and dark a barn owl, white as a ghost, flew almost into my face and I screamed and it made its loud wheezy-sounding alarm cry. Once I walked into a gang of robbers – who were I am sure in retrospect just a group of local youths having an alcohol-fuelled good time. Once someone hidden in the trees whom I could not see let off a rifle that felt very near. And more, I have been frightened in woodland. But on most of these occasions I happened to be in a wood when something frightened me. In Wood of Cree, and years ago in Glen Affric, and once in the birch woods above Loch Hope in the very farthest north, usually in winter and usually at dark-fall and always when I have been alone, I have been frightened by the wood itself. Forest fear. And yet Wood of Cree is such a very pretty wood.

I am not alone. Not by any means. One of the best descriptions of this fear is in Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows:

Everything was very still now. The dusk advanced on him steadily, rapidly gathering in behind and before; and the light seemed to be draining away like flood-water. Then the faces began … Then the whistling began … They were up and alert and ready, evidently, whoever they were. And he – he was alone … Then the pattering began … As he lay there panting and trembling and listened to the whistlings and the patterings outside, he knew it at last, in all its fullness, that dread thing which other[s]. . . had encountered here and known as their darkest moment – the Terror of the Wild Wood.

Poor Mole. Poor me too – except there is also something viscerally thrilling about this fear, something both uncanny and exciting.

*

Read Adrian Cooper’s introduction to the book here.

Arboreal is available now, priced £20.