A new instalment of Mathew Clayton’s monthly column exploring the daily life of a Sussex village in the middle of the 18th century, as recorded in the diary of Thomas Turner. With original illustrations by the author and artist Peter Chrisp.

Turner opened his East Hoathly shop when he was 21 years old in 1750 – four years before the diary starts. He learned the trade from his father who kept shop in Framfield a village just a few miles away. And although East Hoathly had just few a hundred inhabitants his shop sold a great variety of items. The following are listed in the diary…

Aprons, beans, bedding, beehives, brandy, bread, bricks, brooms, brushes, butter, buttons, cabbages, packs of cards, chamois, cheese, chocolate, clogs, cloth, coffee, coffins, cordial, corks, earthenware, cucumbers, currants, fish, fish hooks, flour, gin, gingerbread, gloves, gunpowder, hankerchiefs, hats, horsehair, ink powder, jalap, jewellery, kettles, lobster, Manchester goods (more cloth), needles, oatmeal, onions, paper, pears, pencils, pewter, pipes, potatoes, punch bowls, quills, rabbit skins, raisins, razors, sacks, salt, sand, scales, shaving box and brush, sheets, shroud, silk, slates, soap, spices, spirits, sugar, tea, tobacco, throat hasps (used on horses), thread, weights, wheat, wine and wool.

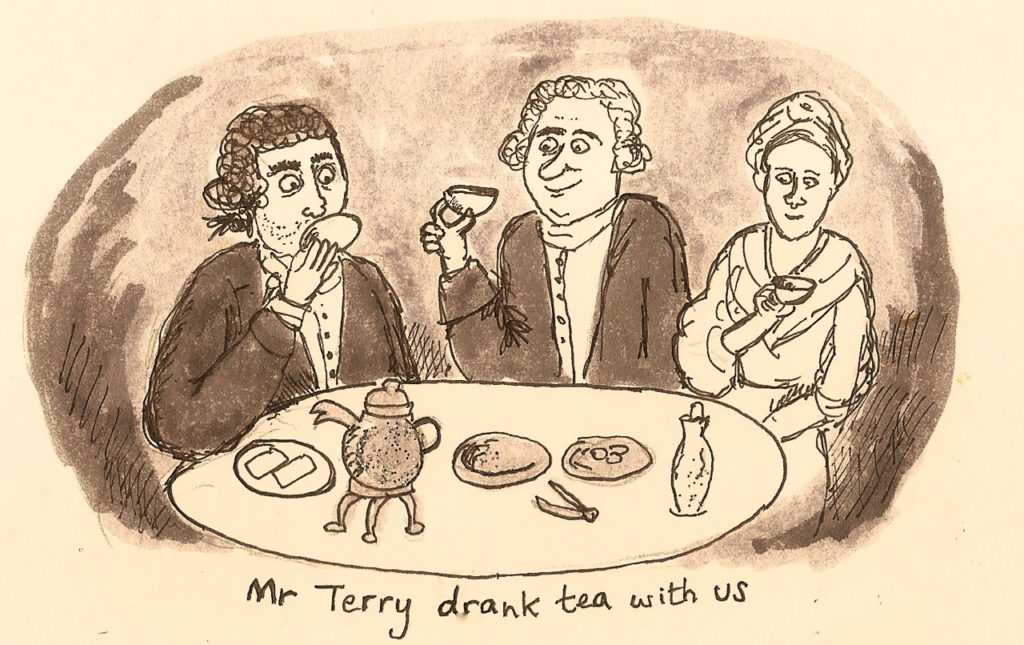

East Hoathly is tucked away in the Weald, an area of Sussex then famous for its mud and unpassable roads, yet Turner received a steady stream of visitors that supplied his shop, some coming from as far away as Manchester. Often they became friends and would stay the night when they passed through, as on Wednesday 17 March 1756 (Jones was the landlord of the East Hoathly pub The Crown)…

‘In the afternoon Mr Terry, the tobacconist, called on me and drank tea with us… I went down to Jones’s with Mr Terry and stayed until 2 o’clock; I spent 12d. Mr Terry I think to be a very pushing man in his trade; he is by birth a Yorkshireman, has been abroad in the merchant’s service in Virginia 1 ¼ years, and rode in the tobacco trade for Mr Albiston before he entered into trade for himself. I was a little in liquor.’

His stock also came from London; in March 1759, he travelled there visiting wholesalers. In a two day trip he visited an incredible 27 different suppliers that ranged from hatters to hosiers, cheesemongers to ironmongers. He travelled to London by horse, setting off at 6.20am and arriving in Southwark at 11.30am. His journey back took a little longer – leaving London at 2.45pm he arrived at 10.45pm. Travelling times round England were being revolutionised by the introduction of turnpikes, where a group of people would take responsibility for improving a section of the road (laying down gravel, making inclines less steep etc) in return for charging a toll. Not everyone was happy with these changes though: the naval commander James Byng commentated, ‘the country is only improved in vice and intolerance by the establishment of the turnpikes. I meet milkmaids on the road with the dress and looks of Strand misses’.

Business was also helped by a countrywide network of carriers that for a fee would transport goods. From Lewes a weekly carrier left the Dorset Arms early every Monday morning and travelling with a wagon at walking pace expected to make it to Southwark by Wednesday night. They would then leave London the following morning and arrive back in Lewes on Saturday night.

In London Turner wasn’t simply buying goods but also settling accounts with people he had communicated with by letter. This was the age before banks and much of Turner’s long-distance business was carried out through bills of exchange – an early form of cheque. His main banker in London was a haberdasher in Borough – Margesson and Collinson.

Whilst his shop was well-stocked Turner often complained that trade was slow, and was continually looking for other ways to make money. Although he was a shopkeeper, a more accurate description of his job might be mercer – a French word meaning a trader in goods. He acted as an agent for his neighbours, selling things like hops or wool to wholesalers. And sometimes he got together with them to buy goods in bulk, as on 28 October 1756… (a ‘tale’ is a measurement of weight and pandle is a local word for shrimp).

‘Mr Porter, for himself, and also for Mr Coates, Tho Fuller, Mr French, Mr Gibbs and myself – in all 6 – agreed with John Fielder to bring us from Hastings a-Saturday next, 1 thousand herrings, Hastings tale and one thousand of pandles for the doing of which we are to pay him 15s 6d and also to pay what the herrings cost on the beach; and then we are to share the herrings and pandles between us in equal share’.

Business was also conducted at local auctions and sales. On February 14 1756 he helped a friend put their house up for a ‘candle’ auction. The candle was lit at 4pm and whoever had the highest bid when the candle burnt out (on this occasion at about 8pm) secured the sale. On the 15 June 1764 we find him attending an auction of confiscated brandy in nearby Newhaven…

‘At about 11.30 I set out for Newhaven, where was to be a sale of foreign brandy at the custom house there. I dined at the White Heart at Newhaven (my friend Tipper not being at home) in company with 5 gentlemen (or at least other men) on a shoulder of mutton roasted, a plain hard pudding, a current butter pudding cake, cabbage and lobster. The sale came on about 3.50, where there were put up for a sale to the highest bidder 78 half ankers of brandy’. Turner bought three lots, 324 pints in total (a half anker was four and a half gallons).

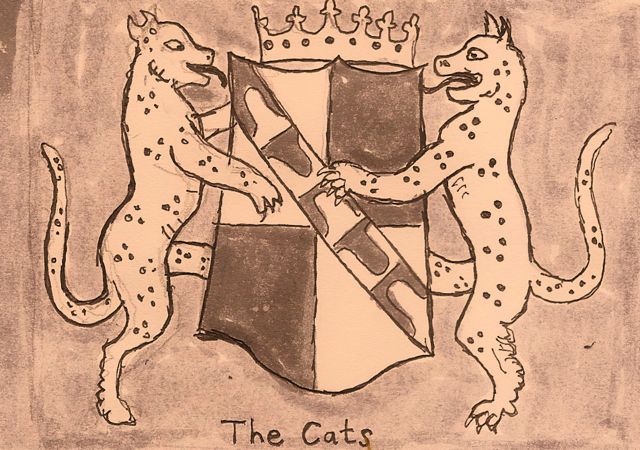

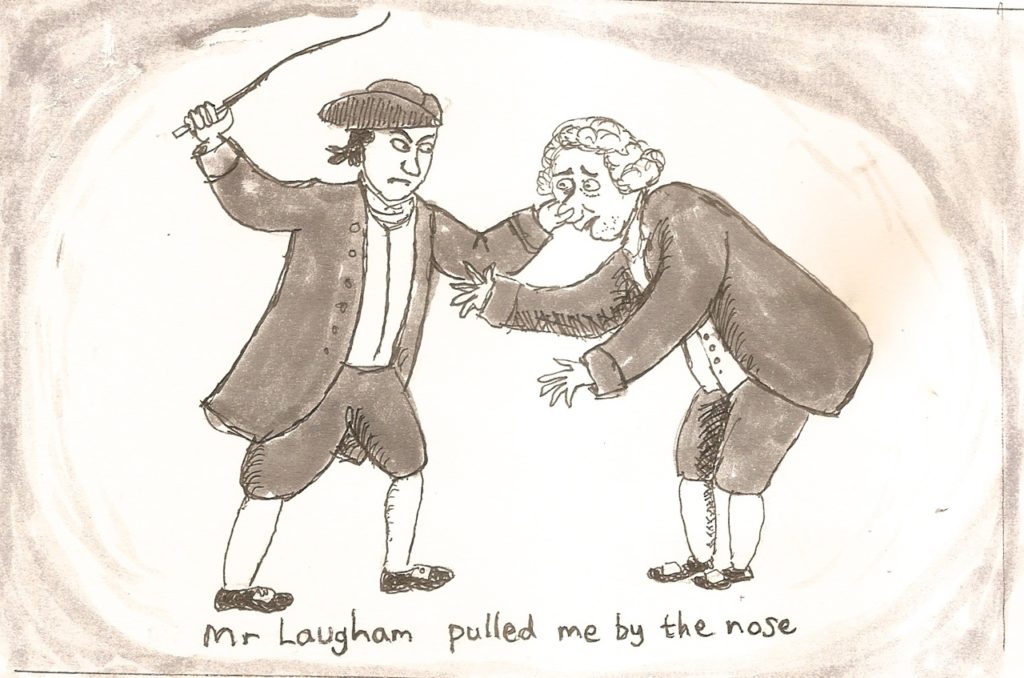

His relationship with his customers was more complicated. Things were often bought on credit or barter and Turner continually complained how impossible it was to get anyone to settle their bills. As we see underneath this could lead to arguments. The pub referred to in this entry as The Cats is actually the Dorset Arms (still trading today), who earned its feline nickname from the two snow leopards on the Earl of Dorset’s coat of arms that featured on the pub’s sign.

Tuesday 8 June 1756

‘My brother and I dined ay Mr Mr T Scrase’s on a cold quarter of lamb and green salad. Paid Mr George Verral 8s 8d in full for 2 doz soap. Now what I am a-going to say makes me shudder with horror at the thought of it. It is I got very much in liquor. But let me not give it so easy a name, but say I was very drunk, and then I must of consequence be no better than a beast. And what is more terrifying, by committing this enormous crime I plunged myself into still greater, that is, that of quarrelling which was this: my walking yesterday and again today, my feet were very sore, so that, meeting with Peter Adams, I asked him to carry me home, which he agreed to do; and I accordingly for on horseback at The Cats after first having some words with a person and I can think for no other reason but because he was sober, or at least I know it was because I was drunk. We then proceeded on the road home, and, as I am since informed, oftentimes finding an opportunity to have words with somebody, and doubtless as often giving somebody the opportunity to sneer and ridicule, yourself, as well in justice they might. And, I suppose, to gratify Mr Adams for his trouble, told him (if) he would go round by Will. Dicker’s I would treat him with a mug of 6d., which he readily accepted of (though he, I understand, was very sober). There we meet Mr Laugham and several more, but who I cannot remember, and I suppose also in liquor. Now there was formerly a dispute between Mr Laugham and I about a bill wherein I was ill used, and I imagine I must tell him of that. Or whether they seeing me more in liquor than themselves, put upon me, I do not remember, but Mr Laugham pulled me by the nose and struck at me with a horse whip and used me very ill, upon which Mr Adams told ‘em he thought there was enough for a joke, upon which they used him very ill and have abused him very much. And whilst they were a-fighting, I, free from any hurt and like a true friend and bold an hearty fellow, rode away on Peter’s horse leaving him to shift for himself and glad enough I got away with a whole skin. I got home around 10 o’clock’.

The upside of this was that his customers were his friends, a visit to his shop could easily turn into an invitation for lunch. Mrs Nant is a nickname for brandy – a joke on the French town Nantes famous for its brandy production.

Friday 29 October 1762

‘Jarvis Bexhill, buying some goods in the shop and it being a very wet forenoon, dined with me on a piece of beef boiled and cabbage with a piece of pork. Dame Durrant made me a present of a goose, and she, Tho., Mr Tipper and Sam. Jenner drank tea with me. I gave the good woman a little of that delicious cordial Mrs Nant’s, a thing truly of greater value than a goose. Oh, that sweet delicious relish! How it enlivens the spirits, gives one all the pleasing sensations that are so agreeable to our nature. And above all when there is too much taken, it renders the most agreeable part of the creation mere brute creatures, as is often this poor women’s case…’

With thanks to John Kay at the Lewes History Group for information about 18th century carriers.