Grey quartz, pink and white feldspar and black biotite mica: in her latest column from the Cairngorms, Anna Fleming explains how granite has shaped the unique landscapes and ecologies of the National Park

Rural Aberdeenshire. An unfamiliar road twists and winds through rolling hills. My feet are busy juggling clutch, brake, and accelerator. The corners are sharp; I am tired but I must concentrate. Navigating yet another bend, I reach a sign: a black silhouette of an osprey, painted onto the face of a pale grey rock. I smile. I’ve re-entered the Cairngorms National Park.

Along the 260-mile boundary, entry points are marked out with granite boulders bearing the Park logo: an osprey in flight, carrying a fish. The bird is a powerful symbol but, for me, the rock on which the bird sits is the true heart of the Cairngorms. The distinctive landscapes and ecologies here – the mountains, plants, animals, peat and soils – are all shaped by granite.

The immense round mountains of the Cairngorms were formed during a period of volcanic activity. Around 400 million years ago, magma rose and filled a huge chamber below the earth’s crust. Within this mould, the molten rock cooled slowly into large crystals of grey quartz, pink and white feldspar, and flakes of black biotite mica. After hundreds of millions of years of erosion, the overlying rocks were ground away, and the vast body of granite now lies exposed.

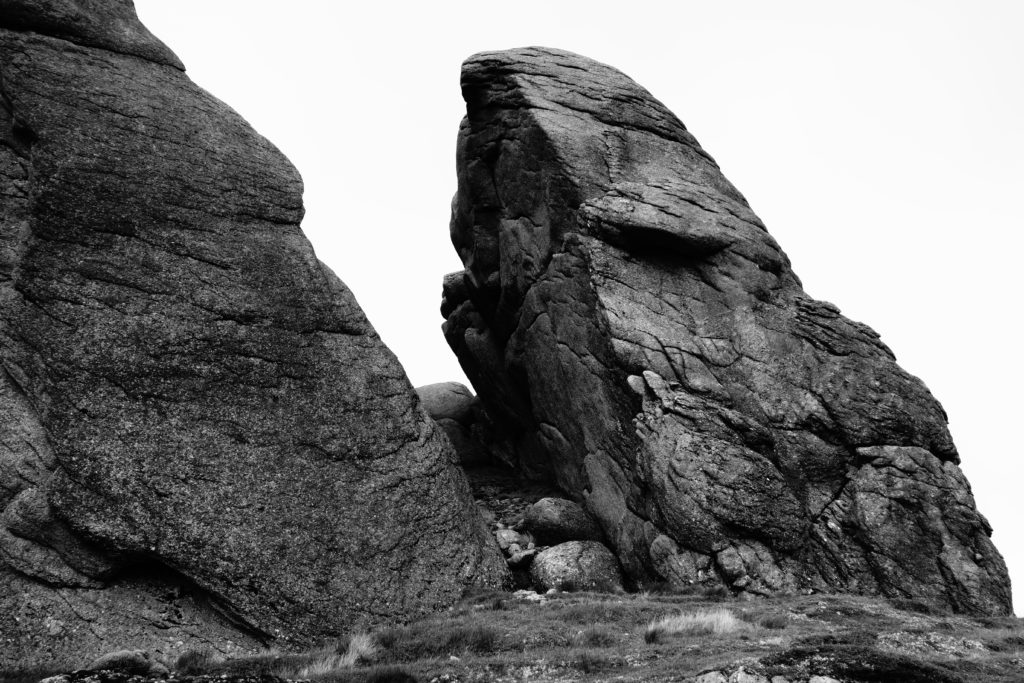

If you venture up onto the plateau, you can find incredible granite outcrops. Tors stud the summits of Bynack More, Beinn Mheadhoin and Ben Avon. These great blobs are up to 15 metres tall and are visible for miles. I have not yet made it to the remote summit of Ben Avon (the shortest route in is a demanding 33km walk), but I always recognise this whale of a hill by the series of granite limpets clinging to its back. Up close, the surfaces of the blocky tors are speckled pink, grey, white and luminous green – a patchwork of rock, crystal, lichen and moss. The glaciers left these upright figures relatively untouched – pushing a tor over here, titling another there, scattering some of the blocks.

Elsewhere, the glaciers had more impact. Rivers of ice gouged out weaknesses, dividing the plateau with the Lairig Ghru and cutting deep clefts like the Loch Avon basin. Above Coire an t-Sneachda, the plateau suddenly ends: undulating kilometres fall away into a sharp vertical drop. In blizzard and white out conditions, meticulous navigation is vital. The glaciers carved uncompromising edges; the corries can be treacherous.

Walking into the corries – vast bowls cut into the mountain, resembling a scoop taken from an ice cream tub – I always feel a slight oppression. The sky shrinks, the cliffs rise. Even when clouds cloak the mountain, hiding the tops of the walls, there is still a looming feel of enclosure. The corries were the birthplace of giants. The glaciers have gone, but their brute, elemental force is tangible. They haunt these icy places.

Once inside a corrie bowl, the foreboding feeling eases. I find myself in immense space. Pools of water hold the sky. Hidden lochans appear, tucked into the hillside, glittering and waving deep turquoise. The water clasps skin like fire. Moving further into the corries, the steep granite walls gain detail. Wrinkles, cracks and slopes emerge. I look with the eyes of a climber and see openings; places where my body could move on rock; dark lines of opportunity.

Savage Slit is one of the deepest and darkest lines in the northern corries. A 60-metre crack set in a corner above Coire an Lochan, the slit runs clean into the granite like a knife cut in butter. Richard Frere, who first climbed the route in 1945 wrote, “It appeared to be very deeply cut in places, and to penetrate into the depths of the mountain.” The name and the situation of the climb caught my imagination. I wanted to get up there, to move with the mountain, to feel my body inside the granite, to explore an unknown corner of the plateau. Fortunately, one balmy July afternoon, a friend was also eager.

To reach Savage Slit, we walked for an hour and a half, following paths through heather and over burns, picking our way between boulders, trudging up steep slopes, feet sliding on moss, grass and scree. Sweet, floral notes hung in the air. We arrived red faced, gasping for breath, the sweat quickly cooling in the shadow of the rock. I looked up and after a few metres of slabs, ramps and broken rock, Savage Slit began: clear, defined and dark. I quickly dug out my climbing shoes, harness, rope and gear. I was eager to get on the rock.

Balancing on ledges, I navigated two rock faces. My feet sought out strong, balanced stances, my hands explored, feeling, grasping, pushing. Squeezing my left shoulder and leg into the slit, wedging in my hips and back, I took a moment. The granite gripped and I let my fingers relax, feeling the joy of movement, focus and exposure coursing through my body.

I peered down into the slit. It runs deep into the mountain, for perhaps twenty metres or more. Tolkien’s Mines of Moria leapt into my mind. Far below, at the murky bottom of the cavity, I glimpsed debris from past mishaps: a water bottle, a harness, a shoe. My stomach lurched – is that my shoe? No. Mine are safely stashed in my rucksack. Higher up, the slit widens. I chimneyed, pressing my back against one edge, my feet walking up the other face. With each step, I thrust my back higher up the slit. The ungainly movement set my gear jangling.

I was climbing at the sharp end of the rope, leading the route. I kept an eye out for cracks and openings where I could protect myself, sliding metal devices in – nuts, hexes, cams – tugging, twisting and adjusting to make sure that the rock held them snug. If I fell, these objects should hold me. I placed gear sparingly: the route is straightforward, the angle easy, I did not need to disrupt the rhythm too often. Promising nooks inside cracks were worn smooth and yellow like ivory – many climbers had paused here too, placing their own protection before me.

At the top, our vision shifted. From micro-rock-focus, we zoomed out to vast space, standing tall at 1,215m altitude. Far below us, the land stretched out tiny towns and turbines, forests, lochs and distant hills. Across the plateau, between moss, lichen and deer grass, the granite gravel beds were luminous, shining like ruffles blown onto the sea. Time had passed. We softened up and allowed gravity to carry us back down the hill. Pink crystals crunched underfoot.