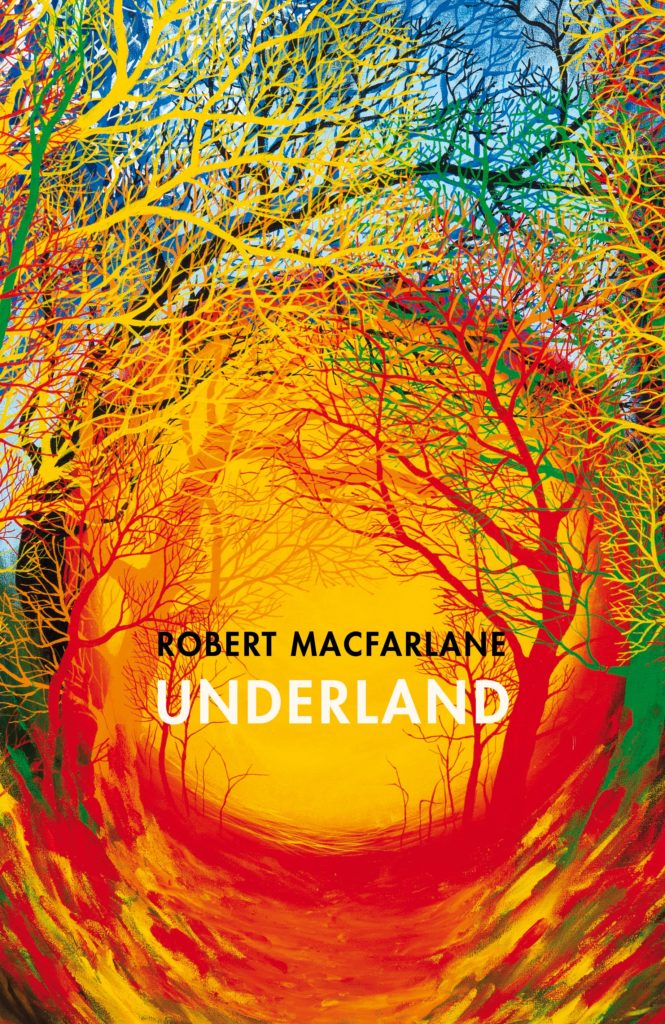

In Underland – Caught by the River Book of the Month for May, published today by Penguin – Robert Macfarlane takes us on a journey into the worlds beneath our feet. Sue Brooks reviews.

What can I tell you about my time in the Underland? It is late evening when I reach the first descent and read ‘though I have been into many caving systems before, I suddenly find swallowing difficult…my scalp swarms with bees.’ Claustrophobia rises. I want to give up, close the book and go to bed. But it’s too late now. I’ll probably have the nightmare anyway. So I read aloud, and in some magical way, it works. The words have body and fly around the room. ‘It is a fascinating and terrible place, and not one that can be borne for long’. Terror, but not my terror, and the writing is glorious. I read on to the end of the chapter and the point of reentry to the above-ground world where ‘everything is shiveringly strange.’ Yes, I have my talisman. Reading aloud will see me through and the journey will be more wonderful and strange than I can possibly imagine.

The structure unfolds: three sections divided geographically – Britain, Europe, The North – and more cryptically – Seeing, Hiding, Haunting. Robert’s long fascination with the eerie is present from the first page – ‘A child drops stones one by one into a metal bucket, ting, ting, ting.’ Scenes are played out on the walls of the first Chamber which might be relevant to what lies ahead, or to some greater purpose which may or may not be revealed. We do not know. The Underland keeps its secrets well, for a while. The chapter entitled ‘Descending’ becomes a touchstone; one which I revisit many times. ‘Underland…is a story of journeys into darkness and descents made in search of knowledge…the line about which the telling unfolds is the ever-moving present. Across its chapters, in keeping with its subject, extends a sub-surface network of echoes, patterns and connections.’

Journeys into darkness and descents made in search of knowledge, many of them long-cherished ambitions, all accompanied by the drum beat of echoes and patterns that become ever more complex. Six and a half years in the writing, several weeks in the reading, and still now, opening the book at random, some nuance in a phrase or a sentence, or a sequence of sentences, takes my breath away.

I begin to see that there are many journeys. The first is to read the story; to start at the beginning and pace myself; to manage the apprehension – looking ahead for a glimpse of what comes next, putting the book down for a day or two before returning – and at the end, saving the last few pages to read slowly aloud, letting the tears come. Except it isn’t the end. Perhaps there isn’t an end to this book, any more than I will be able to write about it in the normal way. Maybe that’s the whole point – that words fail me, because this is a book about the Anthropocene. These are not normal times. The world has changed utterly.

Later journeys have brought deeper levels of understanding – moments when a scene, or one of the lines I have repeated aloud, shines out – if your mind were only a slightly greener thing we’d drown you in meaning. The Kalevala is one of those moments. I suddenly see Underland as a modern Kalevala, an epic for our times, and remember that it was a folk tale, one passed down orally until collected and published in the 19th century. How did Robert put it? ‘obsessed as it is with the power of word, incantation and story to change the world into which they are uttered.’ Yes, there is a point to reading aloud, to reading itself, slowly, with attention, so the full power and music of the words enters deep and changes the mindset of the reader. It is an active process: my mind is making new connections and new commitments follow. There is a wonderful passage in the Epping Forest chapter where Robert and Merlin Sheldrake are talking about the future, about the infinite complexity of the wood wide web, and the need for a language to replicate it – ‘You look at the network and then it starts to look back at you.’

The two sections where Robert is travelling alone have left a deep imprint. Perhaps because I am a fairly solitary person myself, or perhaps because in the Kalevala tradition these would have been testing times, rites of passage for the hero. He sets off in winter at latitude 68 degrees North to find a cave on the western coast of the Lofotens archipelago. Gales are forecast and there is a high risk of avalanches. As the drama unfolds a doubt creeps in.Will he do it again? Will he find the words, the right words when the goal is within reach? He does, of course; most magnificently in this place where magic is powerfully at work, where the veil seems to be at its thinnest and the narrator at his most transparent and open-hearted, ‘weeping for feelings I cannot name.’

Another island awaits. The hero needs to keep a promise. He has been carrying something which must be left behind. He is close to the deepest and darkest place on Earth, and we, the readers, must ask ourselves if we want to go with him. I am thankful that Robert Macfarlane is a superb broadcaster of information. He reads and understands the science and feeds the facts into the narrative in ways which make the natural world all the more astonishing, and the wounds we have inflicted all the more terrible. As he enters Onkalo, I remember the admonishment in ‘Descending’ – ‘Force yourself to see more deeply’. The writing takes on a biblical aspect, a litany which chills the heart. He enters the tomb which is being prepared for the highest level nuclear waste. He knows about other tombs in the USA and the new science that has evolved to devise a language to communicate warning across deep time – nuclear semiotics. ‘Those repeated incantations – pitched somewhere between confession and caution – seem to me our most perfected Anthropocene text, our blackest mass.’

Generosity and comradeship have made these journeys possible. The narrative is full of music, stories, joyful encounters, simple pleasures shared with extraordinary people: the unforgettable Bjornar Nicolaisen – ‘You obey rules. I NEVER do’ – or the urban explorer Bradley Garrett, to whose eyes cities are full of portals previously unknown to the author, hidden in plain sight. Or, my favourite of all, the overnight stay in Epping Forest with the magician.

How to bring this telling to an end, which isn’t an end? Underland is like no other book I have read. It works through so many levels and keeps on working. If we are to understand the Anthropocene, we have to face our deepest fears and move beyond them. Robert Macfarlane has found a way of helping us to do this. It is his masterpiece. When we come to the final chapter – ‘Surfacing’ – in just a few short paragraphs, in simple language, he touches the heart with the utmost tenderness and fills it with hope.

*

Underland: A Deep Time Journey (Penguin, hardback, 496 pages) is out now and available here, priced £20.00.