In her luminous new essay collection, the acclaimed Kathleen Jamie visits archeological sites and mines her own memories — as always looking to the natural world for her markers and guides. Abi Andrews reviews.

Polar bear, wolf and lynx bones, still for 45,000 years, in a cave in the Scottish highlands. A Yup’ik village in Quinhagak, Alaska, at 60 degrees altitude — a straight line west from Shetland. Nunallaq, or ‘Old Village’, rising from its slumber in the permafrost. The Links of Noltland archaeological dig in Westray, Scotland, sifting through an Iron Age settlement and the Neolithic one that came before it.

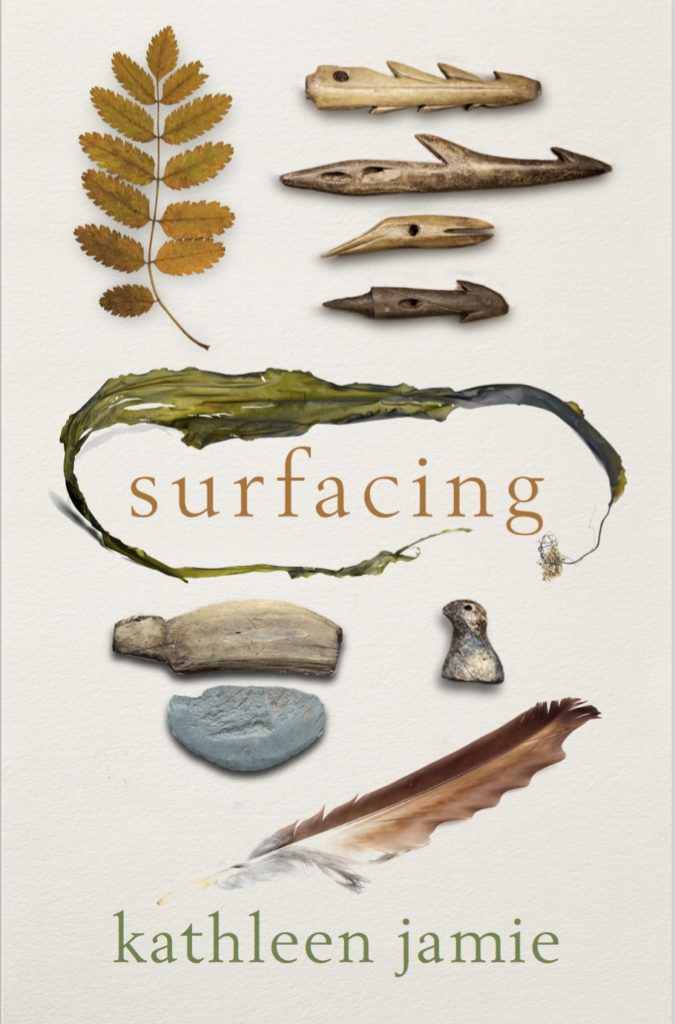

In Surfacing Kathleen Jamie weaves the seemingly disparate across time and place. In a scattering of travelogue, personal memoir, and cultural history, the form of Surfacing itself mimics the strange resonances of its subjects — within the scattering, patterns emerge. Like found objects these musings are offered to us, and each blends into another, making a beautiful midden of the human condition, offering affinities across distance. Objects and memories reconnect us to the past and to personal histories — a continuum, permeable as wide seas and shifting shorelines.

Since this dig began, kids from his village are hunting, carving again. They’re working on the dig, learning archaeology, learning their own traditions.

In a Yup’ik village, a culture that was losing a battle against time is remembered through objects offered up by the permafrost. The lost village of Nunallaq; spat back out of the earth, and with it, ways of being that had been suppressed by colonisers are practiced once again. Time blurs and spirals, a shape that returns. Potential re-emerges, allows for remembering and renewal.

‘Well, the first time that drum hit, the hair on my neck stood up. I thought, It’s back!’

Jamie introduces us to the resilient hunter-gathers with the supermarket selling coconuts. Fiercely autonomous, they come to the page on their own terms. Theirs is an interface, between a past remembered and a future hurtling towards them. They are hot dogs on a scavenged fire, a salmon fishing trip with lollipops. A woman with an iPod in one pocket and her ulu, a traditional women’s hunting knife, in the other.

Jamie evokes their deep connection to the land around the village of Quinhagak, the entanglement between their identity and it. Her sketch of the relationship between land, people and animals there is humane and gentle, and yet beautifully, carefully, mythical.

Transformation is possible. A bear can become a bird. A sea can vanish, rivers change course. The past can spill out of the earth, become the present.

Because it has. The land itself is transformational, and likewise an identity, once suppressed and now reimagining its particularity. For Jamie, this resonates with and offers twinned potential to other places where connection to land has been lost. Like her own Scotland, which once held large predators, erased by dams and big houses with rich private landowners.

And there hasn’t been a wild bear in Scotland for a thousand years.

Where once was a Scottish bear cave, is now a place lonely of bears. Jamie’s subtle inference: they could be welcomed again, if we willed it well enough. Underpinning Surfacing is a tempered insistence on cultural and natural resilience.

Everything you feared you’d lost, or never even knew you had. Look. It’s here. It’s back.

But Jamie weighs hope with a counterbalance, bathetic and poignantly realistic. Any land-connection that returns now is out of kilter. What if this cultural revitalisation is all in futility? Remembered again only to be starved to death, by fires on the tundra, by ice that won’t come any more?

The changing natural world is playing with our chronology. The stirring is throwing up silt, and Jamie links this deftly to the personal. The death of her father, a cancer diagnosis, and her daughter leaving home. All of them characteristically laid bare but looked at sideways. Okay then what now?Here too is an interplay between anchoring and sequestration. Her own life events upset the frost that held her, bringing about another thawing, and another surfacing; that of a selflong buried.

As though on an archeological dig, Jamie comes to similar questions of continuity of self. Time works backwards — things nearer to the surface are the least distant. Memory spirals too — it misremembers, it forgets. When did she abandon the croft for the bigger village? Why did she drop that flint into the snow, there exactly? What was it she felt, that day she was bitten by a dog in a Tibetan village a long time ago? It is the writer’s job to weave the myth of the past, to bring out the patterns like music — dream dogs and vanishing women who lure hunters — and Jamie does this wonderfully.

This is a book in which things come forth as offerings. In Surfacing, the words are not excavated. They shimmer forth, let go of by a force that before had held them. Jamie knows her subjects layer on layer. She is aware of their awareness, she is welcoming of their agency. They keep secrets from her. Truths come of their own volition, as offerings. In prose that is outreaching, generous, and patient, Jamie tells it all: the wildlife and the rusting snowmobiles, the hum of humans just getting along with it. Jamie doesn’t investigate, she notices. We are privy to a conversation in which she partakes.

We watched the tundra, but the tundra, they say, is watchful too.

Seeing and writing like this comes from careful attention and takes time. Surfacing is a book that took five thousand years or longer to write, perhaps — it took that long for the words to come to the surface from their deep origins, and for Kathleen Jamie to notice them.

*

Surfacing is out now and available here, priced £12.99. You can read an extract here.

Abi Andrews is the author of The Word for Woman is Wilderness, published by Serpent’s Tail. You can follow her on Twitter here.